Federal legislation passed in February creates a statutory definition of the employer-employee relationship – and it’s imperative that HR professionals review relevant contracts and working relationships sooner rather than later.

Under new federal laws, our understanding of the distinction between an independent contractor and an employee is changing.

Passed on 12 February – and coming into effect in the first and second half of 2024, and in early 2025 – the Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes No. 2) Bill 2023 introduces statutory guidance for defining the relationship between an employer and a worker.

This guidance states that the relationship should be determined by ascertaining the “real substance, practical reality and true nature of the relationship”.

In other words, explains David Sigler, Senior Associate, Koffels Solicitors and Barristers, “To determine whether a worker is an independent contractor or an employee, regard must be had to the totality of the relationship between the parties.

“[This] means a multifactorial test will apply,” says Sigler.

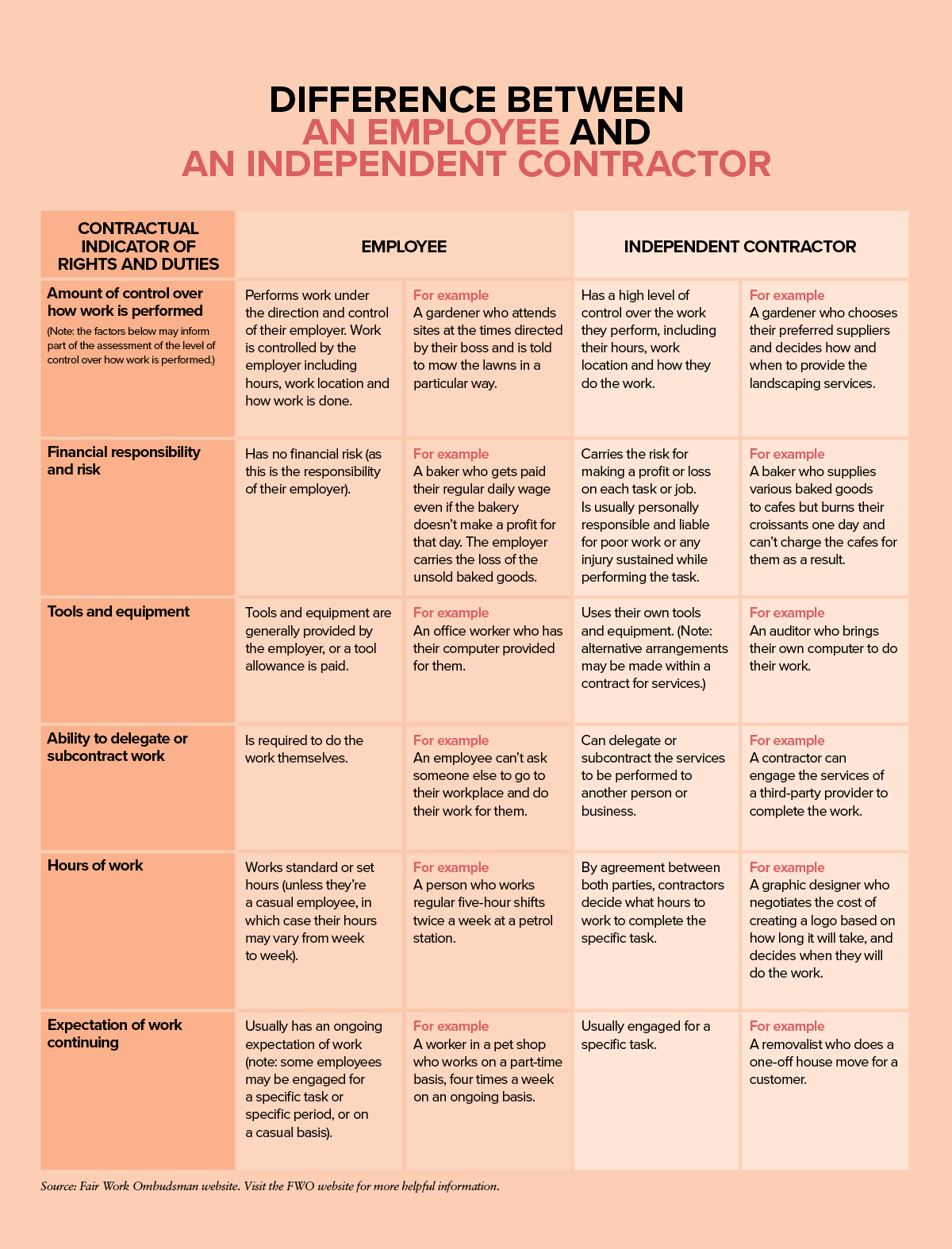

- Factors include, but are not limited to:

- Who controls the work performed, and how it is performed.

- Where financial responsibility and risk lies.

- Who supplies the tools and equipment.

- The worker’s ability to delegate or subcontract the work.

- Whether the worker is engaged by other businesses.

- The expected work hours.

- The expectation of work continuing.

The multifactorial test is not new. Rather, it was usually applied by courts until 2022 – when, in Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1 and ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd v Jamsek [2022] HCA 2, the High Court of Australia determined that where a contract exists, the employer-worker relationship should be determined by that contract – and that the multifactorial test should only apply in the absence of a contract.

Under the new law, the practical reality of the working relationship should always be considered, whether there’s a contract or not.

What might these changes mean in practice? In short, an employer can no longer simply point to a contract to prove that a worker should be considered a contractor rather than an employee.

Instead, it is necessary to assess the relationship holistically, considering the factors listed earlier, as well as others, such as those listed below:

In doing so, it’s important not to rely on any single factor.

“The test doesn’t place any one, or other, indicia as completely indicative of the relationship,” says James True, Practice Group Leader, Employment Law, LegalVision. “All indicia need to be weighed in making the determination.”

An example in action

Practically applying the factors can be somewhat challenging, given there is yet to be a case decided under the new laws. However, previous cases can provide some guidance for HR professionals and employers.

In one such case, a worker was engaged as a tiler/grouter with a company from May 2022 to June 2023. There was no written contract. The worker argued she was an employee, while the company said she was a contractor.

The FWC, in applying the multifactorial test, agreed that the worker was an employee due to a range of factors. First, she did not work for other businesses, and therefore did not carry on a trade or business of her own.

“Where [the worker] exclusively works for the principal or employer, this can indicate employment,” says True.

The fact that the worker submitted an ABN, provided invoices and was responsible for taxation were considered as potentially indicative of an independent contractor relationship, but “not strong reflections of the reality of the working relationship”.

Second, when it came to assessing the level and nature of control over the work performed, the FWC held that the worker could not freely refuse work. This conclusion was based on messages between her and the employer, including the following exchange:

Worker: Can I please have a day off tomorrow?

Her manager: [Expletive], you cannot take a day off. [ADDRESS REDACTED], Go there and roll the glue.

Further, the worker, in performing tasks set by the employer, was required to follow instructions, and did not control her hours, nor how she completed the work.

“Where controls exist [on the employer’s part], it’s indicative of an employment relationship,” says True.

Third, even though the worker supplied tools and equipment, in that she bought the materials needed to perform the job, these purchases took place according to the employer’s instructions.

“Typically, an independent contractor would have their own tools of trade.”

The FWC emphasised that the outcome of the multifactorial test should be determined “on balance and considering the totality of the evidence”.

How can HR prepare?

The first step for HR is to review existing engagements with independent contractors.

“[When] the legislation comes into effect, it will be necessary to ensure that the entire relationship between the parties is considered – in other words, the multifactorial test is applied – to determine whether the relationship has been appropriately characterised,” says True.

It won’t be enough to consider the contract only. HR must look at how the relationship operates practically.

“Where controls exist [on the employer’s part], it’s indicative of an employment relationship.” – James True, Practice Group Leader, Employment Law, LegalVision

If it emerges that, despite a contract, an arrangement resembles an employer-employee relationship, then the employer should make adjustments to ensure the worker receives appropriate entitlements and rights, such as general protections.

“Where [a relationship] hasn’t [been appropriately characterised], there can be exposure to back-payment claims of employment entitlements or penalties for sham contracting,” says True.

Template contracts should be examined particularly thoroughly to ensure there are no unfair contract terms. Terms that could introduce risk might include paying a contractor less than an employee for the same work, placing restrictions on the contractor or insisting on unreasonable working hours.

In addition, HR should be aware that high earners who are already contracted can choose to retain contractor status.

“Existing independent contractors who earn more than the contractor high income threshold may opt out of becoming employees,” says Sigler.

“The contractor high income threshold has not been set, and it may be the same as the employee high income threshold, which is $167,500.”

Finally, it should be noted that the changes won’t apply to businesses that are only “national system employers” due to a state’s referral of powers to the Commonwealth. For these businesses, the cases decided by the High Court in 2022 will still apply.

With just months to go before the new laws are implemented, it’s time for HR to take the bull by the horns and get in early.

This will optimise employer-worker relationships and ensure that all workers – be they contractors or employees – receive the legal rights and remuneration due to them.

This article originally appeared in the April-May 2024 edition of HRM Magazine.

Got an understanding of the basics of HR law and want to take it to the next level? AHRI’s Advanced HR Law short course is designed to equip you with the skills you need.

What an absolute rubbish policy from the Labor government. The High Court provided clarity & certainty in ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd v Jamsek, and here comes the Labor government to rip it away from Australians.