Organisations find whistleblowing quite beneficial. But they still don’t protect whistleblowers, according to new study.

Keeping organisations and individuals accountable for their behaviour has been somewhat of a theme of 2018. We’re seeing more whistleblowers put their neck on the line in order to highlight the wrongdoings of their organisations; often shooting themselves in the foot in the process.

When employees report misconduct 55.5 per cent of managers said it results in a positive action for the organisation, says new research spearheaded by Griffith University’s Centre for Governance & Public Policy (which is made up of a variety of Australian universities, ASIC, CPA Australia and the NZ State Services Commission), titled Whistleblowing: New rules, new policies, new vision. The actions include organisational reforms, management changes, and new training.

Where organisations are still falling short is in protecting those who blow the whistle – both managers and whistleblowers agree that the majority of the time it results in negative repercussions. This means Australia still hasn’t overcome its longstanding issue; why speak up if you risk losing out?

Standards of protection

The research paper covered 46 public, private and not-for-profit sector organisations in Australia and New Zealand, making up 17,778 individuals. It found that 81.6 per cent of whistleblowers said they experienced negative repercussions, such as stress, isolation, and employment impacts (66.3 per cent of managers and governance professionals agreed with this).

Forty-two per cent of whistleblowers said they were treated badly by their organisations (whether that was by colleagues, management or both). The managers and governance professionals included in the research noted that in the cases they witnessed, the whistleblower “suffered harassment and/or direct adverse employment impacts” 34 per cent of the time.

“The treatment and outcomes experienced by whistleblowers continue to fall far short of the level of social and organisational value placed on whistleblowing itself,” says research lead Professor A J Brown.

“The broad conclusion is that, although both public and private companies support whistleblowing as a means of keeping themselves honest at a theoretical level, in practice, the people who inhabit these organisations are generally not so receptive to someone who comes forward with an issue,” he adds.

It’s thought this is the largest dataset around whistleblowing practices in the workplace, and the first to look at both the public and private sector, using the same methodology at the same time.

Do organisations care?

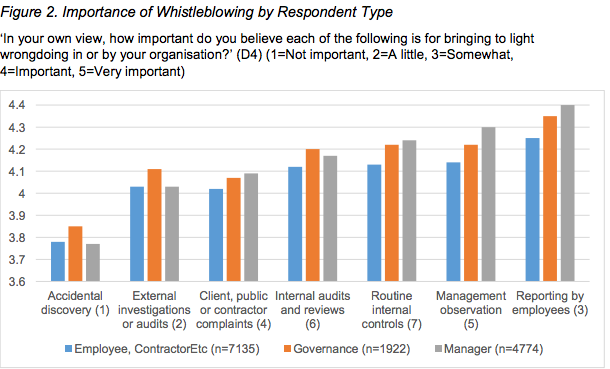

One of the questions the study set out to answer was if whistleblowing was important to organisations; it seemed the answer was yes.

As shown in this graph, all facets of the workforce agree reporting by employees is important. Interestingly, the report also found no difference between the levels of support from public and private sectors.

When comparing negative response outcomes across employee reporters, governance staff and managers; employee reporters fared worst. This isn’t much of a surprise; the lower end of the food chain is usually subject to the worst treatment. Co-workers are more likely to isolate their fellow peer than the person in charge of their fate within the company. But as the report pointed out, it’s concerning that governance staff are facing negative pushback at all, considering their sole purpose within an organisation is to manage these types of risk issues.

Where to from here?

These results, which were presented at a recent symposium in Sydney, line up with the reactivation of whistleblowing protection laws that were put on the table last year.

As HRM previously reported, a parliamentary inquiry outlined a variety of recommendations to protect employees who highlight unethical behaviour and on 7 December 2017, the government tabled a Bill aimed at protecting whistleblowers in the corporate, financial, credit and tax sectors.

The Bill is yet to be passed, but when it is it will directly amend the Corporations Act and will replace existing whistleblowing provisions.

Abigail McGregor partner at global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright outlined that Bill could bring about the following changes:

- Access to compensation and protection against victimisation for whistleblowers

- Penalties for public and large private companies that fail to set up an internal policy around whistleblowing

- Broadening the scope of those who are protected under whistleblowing laws, to include former employees, associates of the entity and family members

- Allowing for anonymous disclosures

- Extending protection to a whistleblower who makes a report to a journalist or politician

McGregor writes for Norton Rose Fullbright: “Whether or not there are any amendments to the Bill, all parties are likely to support the proposal to require organisations to set up internal whistleblower policies. Now is therefore a very good time to review your organisation’s own policy.”

Explore the role HR plays in managing ethics in your organisation and the strategies you can apply, with the AHRI short course ‘Workplace ethics’.

I’m looking forward to finding out whether there is different treatment (good and bad) for people raising personal/workplace grievances such as bullying and harassment, compared to the public interest disclosure issues such as fraud and corruption. The report identifies this as an area of further study. HR professionals are more likely to be responsible for investigating the personal/workplace grievances and are therefore also responsible for protecting the complainant from victimasation, deliberate reprisals and adverse employment actions. Unlike fraud and corruption cases, which can often be investigated without having to identify the source, it may not be possible (or suitable) to… Read more »

I reported to my manager that “our” employer had made materially misleading statements in a mega-millions international fund raising. Three weeks later I got a meeting request in my email to an afternoon meeting for the same day.

I turned up to the meeting. There was my manager and the GM of People. I was fired on the spot, no warning, no due process. And to cap it all off my manager told me I would not ever be given a reference. All whilst the GM of people sat there and listened without intervening.

Not happy Jan.