Many employers are concerned about the wellbeing of staff who’ve been made redundant – as they should be – but what about those who are left behind?

Redundancies are an unfortunate reality for many Australian businesses right now. As we know from the recent results from AHRI’s HR pulse survey, 21 per cent of respondents have already had to downsize. As the year rolls on, that percentage will increase.

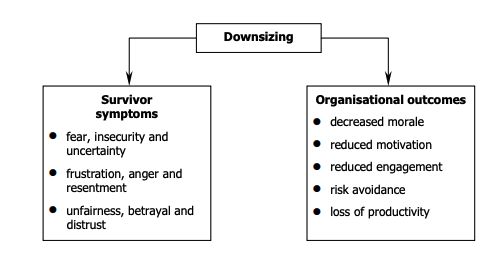

While workplace leaders might feel most concerned with breaking the news to the people being laid off, the conversations don’t stop there. Those left behind can often feel a complicated mix of relief and guilt for not suffering the same fate as their coworker. Organisational psychologists have said this is a type of ‘survivor syndrome’ or ‘survivor guilt’. Left unchecked, it has the potential to be quite damaging to your organisation.

Unpacking it

Survivor syndrome is a common side effect of any trauma. But COVID-19 has increased its prevalence tenfold. Sydney-based clinical and developmental psychologist Romy Kunitz says she’s seeing “a hell of a lot of it right now”.

When having sessions with affected clients, she’s noticed there’s a sense of guilt around even talking about their guilt; they feel they’re being too indulgent or taking up valuable counselling time.

“A lot of people who still have their jobs, who get in touch with their sadness, will say things like, ‘There are a lot of people who are worse off than me’. Which is a normal human response.”

While the typical response may be guilt, survivor syndrome can present in a variety of ways. Employees who make it out of a downsizing unscathed and the managers charged with delivering the bad news often experience reduced commitment to their roles as a result, according to an MIT Sloan Management Review case study.

People may become increasingly paranoid, even those whose jobs are safest, says Kunitz.

“The reason for that is because this whole [COVID-19] situation is a trauma. A trauma of this magnitude, a global pandemic, is going to bring about a situation where your rational brain will shut down and your emotional brain will take over.”

When the emotional brain takes over, especially when this happens en masse, there’s a plethora of behaviours that could impact a business’ bottom line. Here are just a few:

- Less loyalty to the business/leadership

- Overall lack of motivation to continue producing high-quality work

- General low morale

- Lower productivity across the board

- Feeling disgruntled about taking on more work

- Increased stress and anxiety

- Increased absenteeism and turnover

- Freezing up/procrastinating/wasting time

On the last point, a Forbes article suggests these people will be working longer hours in an attempt to make up for their slower productivity. Not only could this lead to them burning out, it doesn’t benefit the company.

“These employees do what they are told but have lost all commitment to the company and are no longer motivated to do good work. Disengagement is one of the leading after-effects of layoffs and leads to a workforce of the walking dead,” says author Jenna Goudreau.

When you consider the financial impacts that can arise from the aforementioned points, it might almost cancel out the costs saved from letting staff go. A piece of research from IRS Employment Review, conducted in 2009, suggests this does happen.

In a 2004 research paper on the topic, Helen Wolfe writes that some people feel those left behind are the real victims. Well intentioned redundancies can pour huge resources into assisting departing employees (counselling services, redundancy packages, relocation money etc.). But historically workplaces don’t pour the same resources into the remaining staff. They’re expected to ‘keep calm and carry on’.

Severing bonds

Due to the amount of time we spend with our colleagues, it’s very common for some to create special connections with each other. HRM has written about how these connections can be a powerful driver towards wellbeing and satisfaction at work. We’ve also talked with people who admitted that their ‘work spouse’ is sometimes the only thing keeping them with an organisation.

What happens when the colleague we trust, confide in or have the most fun with is suddenly out of the picture? These remaining workers are prime candidates for feeling survivor syndrome.

“That affects those left behind hugely. It might affect their concentration or their performance. They might start to feel guilty. They need to be encouraged to process and feel that loss, but not to let it overwhelm them,” says Kunitz.

Kunitz says people who are laid off can’t help but take the news personally – that’s just where our brain goes when we’re dealt a card like this. So as a bystander, when you’re watching someone you care for go through the emotions of what feels like a personal decision, you’re more likely to be upset too. Pair this with the impending stress of your head being next on the chopping block, and you’ve got yourself a cocktail of complex emotions to deal with.

This topic is being discussed over in the AHRI Member’s Lounge on LinkedIn. It’s an exclusive space where over 2,000 AHRI members are coming together to share their stories. Come and join the conversation.

Turning survivors into thrivers

Normalising survivor syndrome is the first step in overcoming it, says Kunitz. But at what point should managers be addressing this? Before redundancies take place or as a support tool in the aftermath? Kunitz says it’s a fine balance.

“You can’t say too much upfront because we need to remember this situation is constantly changing. Because things are changing so fast, managers don’t always know that redundancies are going to happen until the last second. With ‘normal’ redundancies, there’s usually much more planning before they take place.”

Having the luxury of time to craft a careful redundancy plan is something employers can no longer do now that they’re operating in much shorter time frames.

You can also normalise this feeling by having conversations about the departed employees immediately after they leave, says Kunitz, and naming the feelings they might be processing (i.e. saying: “You must feel terrible that so and so has gone” or “It’s normal to feel a sense of guilt right now”).

“This way we can properly understand that this is just a function of the situation and that it’s very, very difficult for everyone. Tell them that it will come right; they will find focus and attention again.”

Kunitz’s second piece of advice is to go above and beyond in making them understand their worth.

“What I hear a lot of my patients complaining about is that they struggle to feel valued. They’re not told enough that they’re doing a good job or that their job is safe.”

As with all communication around the shifting situation with COVID-19, you need to be clear, she says. And staff should be encouraged to consistently communicate with their managers and coworkers.

Giving remaining staff access to EAP services and mental health resources is incredibly important in managing this phenomenon.

She also suggests connecting staff up with each other for check-ins is a good way to allay survivor syndrome.

Other helpful advice HRM came across includes:

- Identify all stakeholders from the beginning: The MIT Sloan Management Review paper reminds leaders to consider all stakeholders in a redundancy, not just those being let go. That means staff left behind, their managers, the communities they’re involved with, their clients etc – then organisations should set up support teams for each stakeholder group.

- Implement engagement programs – IRS Employment Review’s survey of 116 employers found that employee engagement exercises were helpful in a quarter of cases. This was combined with clear communication (86 per cent agreed), involving staff in change programs (48.5 per cent) and consulting staff on the implications of redundancies (81 per cent).

- Create a ‘Realistic Downsizing Preview’ (RDP) – Wolfe says when employees feel prepared, they’re able to create more effective coping strategies for themselves. The idea of an RDP is that a communication framework around redundancies exists before they take place. This, she says, acts as a “psychological contract between surviving employees and the organisation” and helps them to feel like active stakeholders in the process.

Finally, giving people hope is also really valuable.

“People need to be reminded that this situation is temporary,” says Kunitz. “That needs to be said. It sounds so simple but these are things that often aren’t communicated and then there’s no sense of relief for that person. It’s more than just words; it really goes a long way.”

HRM would love to hear about your experiences of survivor syndrome. If you’d like to share your story (you can choose to remain anonymous), please feel free to reach out to Kate at kate@mahlab.co.

During the COVID19 some business are making employees redundant in the most inhumane way possible were they are not concerned at all with employee welfare.

I suffered the wrath of the redundancy serpent in a period of another virus created by Campbell Neiman and his cronies. Mistakenly I pored my whole life into one of his departments and was spat out of the system like a sausage machine. I have never recovered and my mental illness is now chronic. The second attempt on my life was last Sunday night. My family is still in shock. At least becoming redundant from a position created by a pandemic is almost predictable. The way we where treated was in many aspects bordering on criminal. My heart goes out… Read more »

[…] Managing workplace survivor syndrome after redundancies […]