Research from 12 years ago accurately predicted what we’re all going through now.

Humans evolved as social animals. If there is one thing that your tribe or family have that others don’t, it’s proximity. So there is perhaps no stronger bias than the one we have for the people we see most often or sit next to at work.

It’s easy enough to detect with even the simplest of hypotheticals. Assuming they have an equal need, who are you more likely to lend $100 to, your neighbour or that guy who lives four blocks away?

This bias is becoming a problem in organisations, one that might get worse post-COVID.

The pandemic has been a boon to remote work, and has transformed a lot of office teams into virtual teams, but it has also created hybrid or blended teams (a mixture of virtual and office members). If and when this becomes normal, the human bias for those we’re physically close to could result in harmful outcomes for employees and employers.

HRM has written before about how to manage the in-group, out-group issues that can develop at the workforce level, but it’s possible the most pernicious effects will be felt at the team level.

The power of group identity

Interestingly, some of the research about how this will be the case is quite old. A 2008 study published in The International Journal of Human Resource Management surveyed the IT employees of a global company. The researchers categorised participants by those who had been in completely co-located, semi-virtual (hybrid), and completely virtual teams and assessed things such as communication frequency, cognitive and affect-based trust, perceived skills and project satisfaction.

Like many people during the last few months, my recent experience has parallels with the research. This year I have been a manager to all three different kinds of teams. It’s not that the team members ever changed, but where we worked did. Before the lockdown began we were all in the office, during lockdown we were all in our respective homes, then, as restrictions eased, we came into the office as needed.

Reading through the research, the parallels became even more apparent.

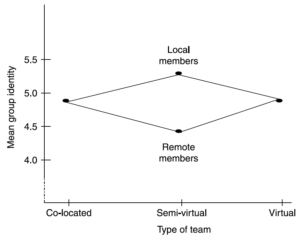

To the researchers’ surprise, there was no significant difference between the feelings co-located workers had for one another and the feelings virtual team members had for one another. That is, a team that works entirely in the office together had a similar level of ‘group identity’ as those who worked entirely remotely.

The researchers were again surprised to find that the teams with the highest level of project satisfaction were the entirely virtual teams.

Today these findings are perhaps not as shocking. The pandemic has shown that people love remote work. Comments from the research subjects mirror sentiments many have felt since being forced to work from home, including the following:

“Productivity time is lost in commutes. Telecommuting allows flexible work time and actually institutes longer work days as during evening hours, there is typically an opportunity to prepare for the next day or take care of emails from other parties located in other geographical areas… [virtual] teams should become the norm, not the exception.”

The type of team that was a lot less likely to have cohesion was the semi-virtual variety. In fact, in the entire study the team members who had the highest levels of trust and group identity were the in-office members of hybrid teams. Those who had the lowest were the remote members of hybrid teams.

Souce: International Journal of Human Resource Management

Souce: International Journal of Human Resource Management

Distance itself doesn’t create in-groups and out-groups, it’s being close to some and distant to others that causes an issue. Comments from both those in and out of the office are illuminating.

- (Remote) “It is particularly difficult to work in a team that is mostly concentrated at one site, and you are the remote one.”

- (Local) “Synergy is lacking for the team when there are remote components. There are limits to the virtual team and the members that come to the office within [company name], do most of the real work.”

- (Remote) “My experience with remote management is totally negative. The people who were not remote without fail had more opportunity.”

Again, this aligns with my own experience. Even though I made sure I was trying to make sure I was fair, I found that on days where I was local with other workers, I naturally favoured giving them extra tasks (which maybe they didn’t consider all that nice of me).

There is no particular reason why this should be the case, but it felt so much simpler to ask someone out loud, “Hey, do you mind checking this” rather than type the same thing. Perhaps more understandably, I joked and commiserated more easily with the people I sat next to than I did those with who were remote.

The researchers did not test for intersectionality – for factors that might make the in-group out-group dynamic even worse. For example, the nature of living with a disability often means it’s more convenient to work remotely. Now imagine a situation where the unconscious bias against those with a disability coincided with an in-office bias against remote workers.

What can be done?

The pandemic has meant these hybrid situations have happened for a few days here and there for my organisation. But if you extrapolate my behaviour with a hybrid team to a permanent manager with a hybrid team, you would start to see in-office team members not only get more opportunities, the camaraderie of proximity would cause an in-group to form in an organic way, with potentially huge impacts on career development, team cohesion and job satisfaction.

The situation could possibly be reversed if a manager was remote. The manager would feel more camaraderie with the other remote workers, while the local workers might all feed off each others’ sense of ostracisation.

It sends a powerful message that the researchers felt confident enough in their findings to recommend that “all team members should be ‘in the same boat’, that is, all local or all remote”. They do however offer advice for situations where hybrid teams are unavoidable.

- Have leaders define a vision for the whole team, “generating passion around a cause” that will help them find the “big picture”.

- Have managers break down the formation of in-groups and out-groups by reinforcing every person’s sense of working on their specific part of the project. So rather than addressing the office team and the remote team, address each and every member individually.

- Train team members to be more mindful and to hone their ability to make distinctions. This needs to happen early, before people categorise themselves and become resistant to training.

- Conduct periodic face-to-face meetings with everyone.

- Conduct virtual team training, where everyone works together on the same online challenge.

As more permanent flexible work frameworks are shaped by HR professionals, they would do well to think about the risks of hybrid teams. If they are required, mitigating the creation of in-groups and out-groups early could improve engagement, productivity, job satisfaction and, ultimately, retention.