The mistake many employers make is designing burnout solutions that cater to individuals. We need to look at the issue through an organisational lens, says new report.

Many employees are overworking this year and it will likely catch up with them sooner rather than later.

The 2020 Workplace Burnout Study, which surveyed 1,760 people from 16 different countries (including Australia), found the pandemic has exacerbated work pressures and stress. As HRM reported earlier this week, this stress and anxiety is contributing to Australia’s $220 billion mental health crisis, meaning this shouldn’t be viewed as an individual or workplace issue, but an economic one.

Forty-two per cent of survey respondents reported feeling some level of burnout this year, with over 30 per cent reporting they’re feeling less productive and producing lower quality work over the last six months.

But rather than offer advice and resources to help individuals burning the candle at both ends, this research investigates the organisational structures and working conditions that cause burnout – and offers advice for addressing them.

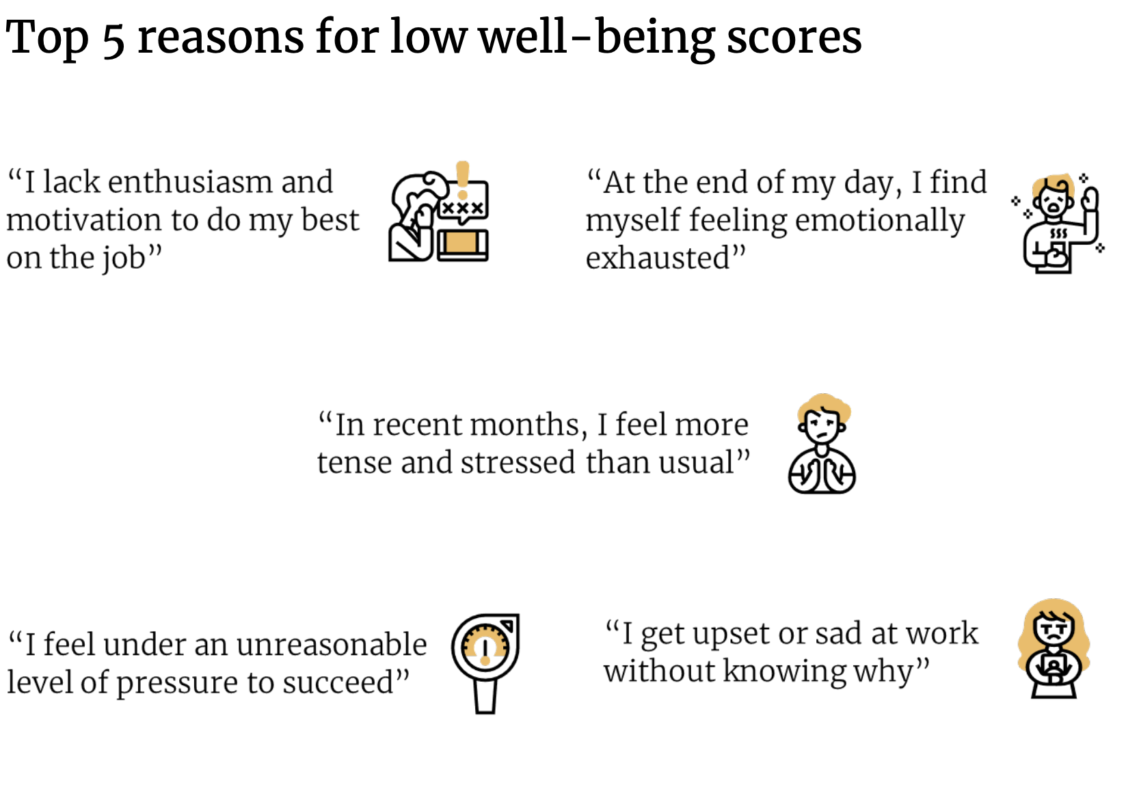

Five top reasons for burnout

The author behind this study, industrial/organisational psychologist Dr John Chan, says organisations need to play a greater role in burnout prevention.

“Organisations are getting better at addressing individual wellbeing. However, when it comes to burnout, I don’t think most workplaces are getting better, mainly because they’re not asking the right questions,” he says.

Chan’s report identified five organisational factors that are contributing to employee burnout. The first was unfair treatment in the workplace, followed by an unmanageable workload, unclear communication from managers, a lack of manager support and unreasonable time pressures placed on tasks.

Participants were 63 per cent more likely to take a sick day this year and 2.6 times as likely to be actively seeking a new job, compared to non-burnt out staff.

“Instead of asking what organisational structures and cultures are causing burnout, [employers are] asking, ‘what can we do for this individual’?”

Because we keep focusing on the individual, it creates a stigma – “that something is wrong with that person and that’s why they’re burning out,” says Chan.

“And so all the solutions are about that person (such as taking some time off), rather than looking at a workplace’s structural issues. Perhaps someone is burning out because they’re wearing multiple hats or they don’t have a say in [their work responsibilities], etc.”

“People don’t burn out in isolation,” Chan adds. “You can be pretty sure that if one person is burning out, other people are in the same boat or close to it, and it can get bad pretty quickly.”

Not only do managers and HR leaders need to look at the root causes of burnout from an organisational perspective, they need to think of the impacts through this same lens.

Chan’s report points out that widespread burnout leads to reductions in performance (which is often passed onto other team members) and increased absenteeism and turnover – participants were 63 per cent more likely to take a sick day this year and 2.6 times as likely to be actively seeking a new job, compared to non-burnt out staff.

Burnt out employees were also twice as likely to try to convince one of their colleagues to leave the job with them, Chan’s report found.

Also, at a point in time where it’s crucial to think ahead and prepare for the future, burnt out employees will hold you back because they “are not thinking about the future, they are in survival mode,” he adds.

Who is most burnt out?

There has been plenty of press attention around the greater pressures placed on women during the pandemic – such as taking more responsibilities for childcare and assisting with remote learning.

This isn’t to say it hasn’t been tough for men too, however, the survey found that in general, women experienced a higher prevalence of burnout this year. Over half (54 per cent) of the women surveyed rated lower than the median wellbeing score (49 out of 100), and 44 per cent of male respondents were in the same boat.

“One of the things that COVID-19 has done is push a lot of responsibilities and blend them together as we work from home,” says Chan. “So there are all of these extra things that women especially have to balance.”

“You can be pretty sure that if one person is burning out, other people are in the same boat or close to it, and it can get bad pretty quickly.” – Dr John Chan

“What I thought was really interesting was that the research showed there were no differences between people with caring responsibilities and those without in terms of the rate of burnout or even their overall wellbeing,” he says.

Those aged 35 to 54 had the lowest wellbeing scores of all the age groups. And when looking at management levels, those in entry level positions (less than 5 years’ experience) and middle management were most likely to report low wellbeing scores.

A prevention method

Common signs of burnout include feelings of exhaustion and alienation, cynicism towards one’s work and reduced efficacy, says Chan. So it’s important have prevention mechanisms in place to avoid burnout.

“By the time an employee says they’re experiencing burnout, it’s almost too late at that stage.”

Want to strengthen your mental health awareness and learn stress management strategies? The Ignition Training half-day course Mindfulness – Mental Health at Work will equip your team with helpful strategies to build a mentally-healthy workplace.

Wellbeing and resilience initiatives – such as yoga or mental health days – are a good way to optimise individuals’ stress management strategies, says Chan, although the best approach to get on the front foot of this emotionally and financially draining phenomenon is for change to come from the top.

“Senior leaders are the most important players in recognising the importance of this issue and prioritising it like they would any other business issue,” says Chan. “It’s not just a touchy-feely thing to make sure everybody gets along; there’s a real business impact if you don’t focus on it.”

Workplaces also need to prioritise management training, according to the report, because the more leaders understand about the commercial impacts of burn out, they more likely they are to help co-design solutions to overcome it.

For example, organisations need more data to be able to effectively roll out burnout prevention initiatives. Managers can help make this happen, but HR’s role here is critical.

Chan suggests HR departments look at integrating data from different areas of the organisation to create a dashboard or data set which enables more insights, and introduce listening strategies to ensure you’re hearing your people’s concerns.

“What you should be looking for are people who have significant drops in their performance, especially those who were at the top levels of performance and then have a sudden drop,” he suggests.

“The people most prone to burning out are high performers; the people who are super passionate about what they do and almost can’t help working themselves into a burnout situation,” says Chan.

The report also suggests reviewing the roles and job structures in your organisation to design “sustainable roles performing purposeful work”.

We’re at the tail end of a year that has worn down employers and employees alike. Rates of unpaid overtime have skyrocketed, isolation has held us back and we’re all so damn tired after a year packed to the brim with tension, uncertainty, loss and anxiety.

So taking the time to get a clear picture on how many hours your employees are putting in – and the state of their mental health – needs to be a top priority before we march into 2021.

Insight article which truly highlights the causes of burnout.