More power in employees’ hands, better flexibility options for blue-collar workers and insights into whether or not employees are productive when working from home. HRM unpacks the Productivity Commission’s latest report.

Remote work might conjure thoughts of employees tapping away at their computers, hashing out details with colleagues via a video call or squeezing in a few loads of laundry between meetings. This could lead you to believe it’s the domain of the 21st Century employee, but the truth is, working from home is a decades-long practice, centuries even.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, many people’s homes were broken into sections designated to various types of work. In Japan, during the 11th and 12th Centuries, merchants would sell their wares from what are called machiya – a space built in front of their homes. English and North American culture spawned the ‘longhouse‘, a space where servants lived and worked, conducting tasks such as weaving, cooking and sewing clothing.

It was only in the 20th Century that our homes became spaces for rest and leisure, not work. So, in a sense, this recent spike in remote work is a full circle moment for human civilisation. How will this play out post pandemic?

A new report from the Productivity Commission has taken a deep dive into some of the latest research on remote work, including who’s most likely to take it up, the arrangements employees want in the future and the potential gaps that employers can fill.

Topline insights include:

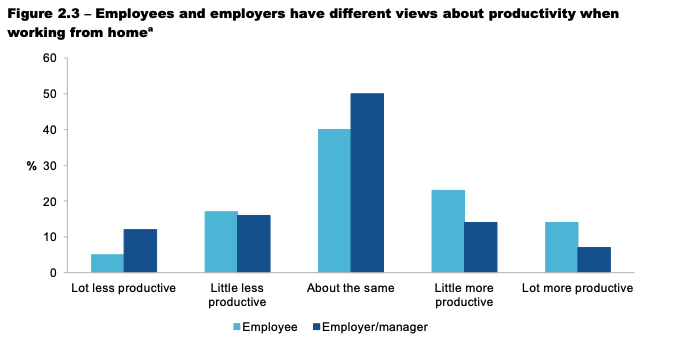

- Most employees feel they’re just as, if not more, productive when working from home. However, the research on this is mixed. Employers are less inclined to think productivity rates have increased.

- Remote employees are saving an average of 67 minutes per day without their commute and around $49 per day for those who drive to work, based on foregone earnings, and $57 per day for those who use public transport, based on time value and transport costs. Commuting one day less per week over a work year would save the average employee the equivalent of seven days in travel time, and nearly $400 in public transport costs.

- A lack of flexibility will hurt employers, with research showing that around 40 per cent of employees would look for a different job if their flexibility was taken away.

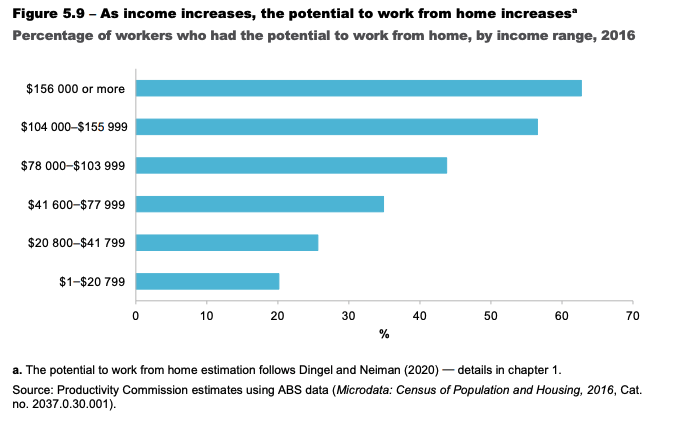

- Full-time ‘knowledge workers’ with a high income and a high level of education are the most likely to be able to work from home.

The extensive report expands on the points above in detail, but HRM will be focussing on three main points: shifting power dynamics, rates of productivity when working from home and flexibility for blue-collar workers.

Remote work: rise, fall or plateau?

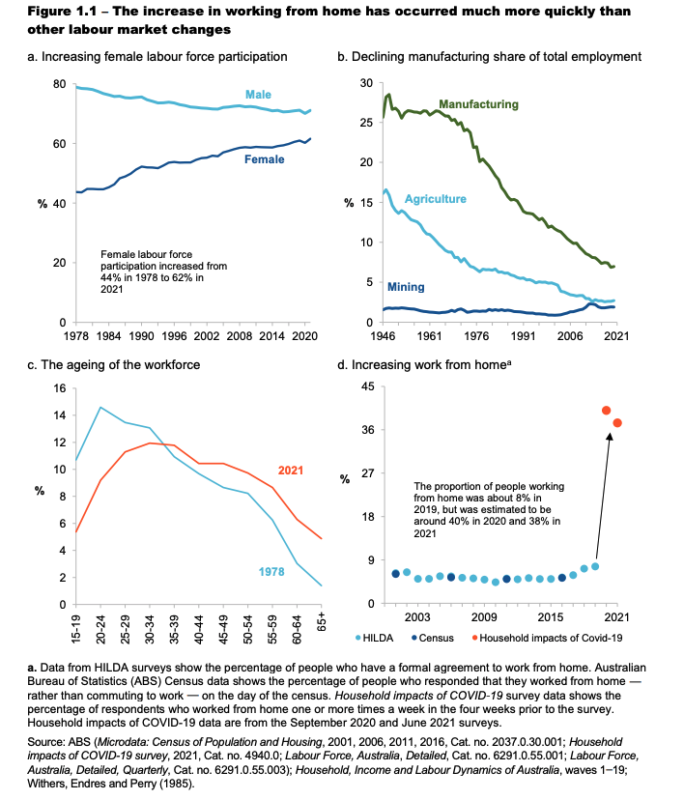

The report points to data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey which suggests remote work uptake has historically been low, with 2016 and 2019 results showing that only 5.3 and 8 per cent of Australian workers were working remotely.

Experts suggest this low adoption rate is linked with the stigma associated with remote work, such as employees using it to slack off or women working remotely to balance caring duties, which many previously marked as a career killer due to proximity bias, amongst other things.

Today, almost 40 per cent of the Australian workforce is working remotely, the Commission found, with remote work now the fastest-growing workplace trend that we’ve seen in decades (see graph below).

Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t seem like it will disappear when lockdowns are finally over for good.

Now that there are rumblings of locked down workplaces reopening in the next month or so, when the relevant vaccination targets are hit, employees are starting to wonder what the future holds.

More power in employees’ hands

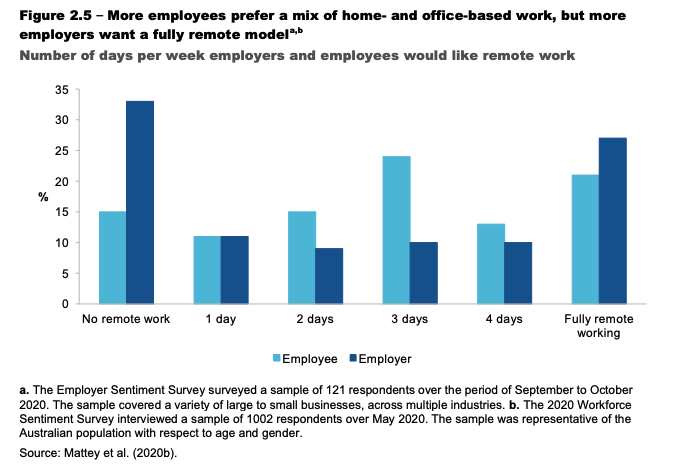

While the authors of the report are hesitant to predict exactly what future uptake of remote work will look like – suggesting we could see an inexorable increase, a steady state or a measured retreat – it’s pretty clear that we won’t be returning to previous approaches, and employees won’t be shy about letting their expectations be known.

“Between 40-50 per cent of the labour market are looking to leave their employer in the next 12 months and, with 100,000 more jobs in Australia than pre-COVID alongside record high vacancies and historically low unemployment… We are about to see a massive exodus of workers,” says Dr Ben Hamer CPHR, AHRI Board Member and Future of Work Lead at PwC.

“Therefore, employers need to listen to their employees. There’s no going back to the way things were.”

Recalcitrant employees need that message to sink in, as the report indicates that employees would be willing to call it quits if their flexibility expectations weren’t met. Some employees have even said they’d take less pay in return for the ability to work from home.

According to US research quoted in the report, the ability to work from home for 2-3 days per week moving forward is worth a 7 per cent pay increase for the average employee. Other research suggests employees would even cop an 8 per cent decrease in pay in exchange for the option to work from home.

While these are significant findings, the Commission is wary of placing too much emphasis on them, stating that “the valuations expressed in surveys do not always translate into real world behaviour”, and it’s relatively uncommon to hear of wage decreases. Whether it eventuates or not, it’s indicative of how much value employees place on remote work.

Giving employees a choice as to how, where and when they’d like to work can increase their motivation levels. As HRM previously reported, research indicates that when you eliminate employees’ opportunities to choose when/if they engage in remote work, motivation levels plummet.

The Productivity Commission’s report echoes this, stating that this type of autonomy increases both productivity and job satisfaction.

This could all very well signal the start of a movement towards increased autonomy for employees in other aspects of work – such as the adoption of democratic leadership models.

As the report notes, remote work is one of the first big workplace trends that benefits employees and employers alike. In the past, shifts such as the introduction of production lines and widespread adoption of electricity, for example, tended to solely benefit employers.

This trend is happening on top of Australia’s tight labour market and high vacancy rates.

“When this happens, the labour market tightens and we see a war for talent. Normally, organisations would throw money at workers, pay rises, sign-on bonuses, retention bonuses – you name it. But, given this is happening off the back of Australia’s largest work-from-home experiment, and only 10 per cent of Australian workers want to go back to five days a week in the office, [employer’s] hands are being forced.

“There was a large number of senior executives across Australia who were quietly hoping things would just go back to the way things were, which we know won’t happen, and so it’s fair to say they’re uncomfortable [with the power shift].”

“There is no going back to the way things were.” – Dr Ben Hamer CPHR, PwC Future of Work Lead and AHRI Board Member.

While the job market will likely settle soon, Hamer also says “the stage has been set”.

“Somewhere between 40-50 per cent of workers are currently thinking about leaving their job. And given that Australian HR leaders told AHRI pre-COVID that they’d like turnover to be sitting somewhere between 1-10 per cent, this is going to come as a rude shock.”

The way to respond to this, he says, is to re-imagine the Employee Value Proposition, and ensure they’re personalised and reflective of employee’s remote work wishes.

“Within society, we’re seeing products become increasingly tailored and personalised, and so employees are coming to expect this from their work too.

“In five years time, we will look back and see that some organisations no longer exist, or are much smaller, because they failed to adapt,” he says.

Are we really more productive working from home?

The evidence around productivity levels when working remotely is mixed.

Research from the US, quoted in the report, suggests that forced remote work settings increased the usual work-from-home productivity levels by 46 per cent. While the report doesn’t expand upon why, we can assume this has something to do with the universality of the arrangement.

There’s no longer just one or two people logging in from home; virtual work had to be conducted from the top down, meaning more investments were made into securing adequate resources, technologies, processes and mindsets.

The report cited research based on call centre workers found that a quieter and more convenient home-office environment increased productivity by around 4-7.5 per cent.

However, research conducted on the productivity levels of those in “more complex jobs” found that remote working during the pandemic decreased productivity from anywhere between 8 and 19 per cent. It’s important to factor in the potential mental health impacts of the pandemic and huge overworking tendencies we saw last year – both could certainly influence those numbers.

But even if we focus solely on the positive research, the Commission still found a discrepancy between employers’ and employees’ perception of productivity levels during remote work arrangements (see graph below). Employers were more likely to think productivity rates had dropped or stayed the same.

“There are some CEOs and senior leaders who believe that people aren’t as effective working from home or that they need to get people back to the office as soon as possible. Both are fundamentally untrue,” says Hamer.

Employers might just have to get a little more creative about how they’re facilitating flexibility.

“Flexible working shouldn’t mean that employees simply inform their employer of what they’ll do and when. It comes down to what works best at the team level and for team effectiveness, and middle managers need to be empowered to make these decisions.”

To do this, he suggests business could offer flexibility around start and finish times, for example, while having some core hours in the middle of the day.

“It could mean timeboxing when work needs to be synchronous – everyone online or on site together – or asynchronous, when people can be offline for deep thinking work.”

It might also be best for us to stop thinking about productivity entirely, in terms of remote work, says Hamer.

“It’s something that was used to measure production in factories – it’s output over time. But with people working from home, it just doesn’t make sense as it has nothing to do with the quality of work. Instead, what we’re talking about is effectiveness.”

Flexibility outside of white-collar workforce

Another important, but not surprising, finding was the profile of someone most likely to be able to work remotely. They were white-collar, full-time employees on high salaries with a high level of education under their belt.

There are growing calls for those who employ people who don’t fit that bill to come up with alternative options.

As HRM reported last week, blue-collar workers want similar levels of flexibility to their white-collar counterparts in terms of where and when they work, who they work with, the type of work they take on and how much they do.

“Only 35 per cent of Australian workers are able to work from home based on their role,” says Hamer. “So we are talking to the minority. It’s not to say it isn’t an important topic, but we shouldn’t disproportionately focus on it.”

“Only 35 per cent of Australian workers are able to work from home based on their role,” says Hamer. “So we are talking to the minority. It’s not to say it isn’t an important topic, but we shouldn’t disproportionately focus on it.”

Organisations with a dual workforce are seeing some tensions and cultural issues at play, he says, with some frontline workers feeling they’re not as trusted given as much flexibility as those working from home.

But just because remote work might not be an option for some blue-collar professionals, that doesn’t mean they should be missing out on the new widespread flexibility that their white-collar counterparts are enjoying.

Hamer says employers should think about:

- What else can you offer? “When we think of flexibility, we think of working from home, but it’s so much more than that. Be clear on what flexibility is and what’s afforded to workers, from things like shift-swapping to rostered days off.” You can also offer short work days, in some instances, or alternative start and finish times to suit a front-line worker’s personal life.

- Change the language so it’s not about flexibility but choices. “Irrespective of what role you have, there are choices you can make and options afforded to you that provide flexibility. Framing around choices brings a sense of control.”

- Upskilling opportunities: “Blue-collar roles will have some, or in fewer instances all, of their work automated over the coming years. This provides opportunities for reskilling and up-skilling to new roles, like truck drivers who now operate vehicles behind a computer screen, with different flexibility provisions.”

How is your organisation approaching the future of remote work? Let us know in the comment section.

Want to get ideas for your future remote work policy? Keen to find out if your peers think employees are more productive working from home? AHRI members can start a conversation with their peers over at the AHRI LinkedIn Lounge. Join today.

Very comprehensive article, and helps one to consider the bigger picture

I think we can be more productive working from home. It probably depends on the person and the type of work. Regardless of that, I think productivity tools are helpful, especially when you work from home. I recommend kanbantool.com, it’s a great project management tool and a collaboration tool. My team definitely benefits from it.

I think it all depends on how we organize our time. When you struggle with time management, you might want to use a time management tool, for example, kanbantool.com. It’s an easy but efficient solution that gives positive results almost immediately.