In some instances, we can use productivity guilt to our advantage. HRM looks at how it might have benefits to boost performance – just don’t let it dominate your thinking.

Most people reading this would have likely experienced productivity guilt at some point in their careers. Who hasn’t felt anxious about not starting a project sooner or watching unopened emails pile up in their inbox? Perhaps you’ve even found yourself engaging in panic working.

Procrastination and an inability to focus seem to be part and parcel of our hyperactive working lives. And while this certainly existed before the pandemic, it has ramped up in recent years. HR professionals in particular have been forced to add more to their plates, meaning productivity guilt has likely become a common experience in their working weeks.

It’s common to feel as if the days are getting shorter, and it’s rare to feel 100 per cent on top of everything. But when that guilt starts to impact your performance, mental health or team cohesion, it’s likely time to figure out a better way forward.

Productivity guilt can feel like a curse – so what can we do about it?

A little guilt goes a long way

The irony isn’t lost on me that when putting together this piece, I felt a lot of pressure to knuckle down and meet a deadline. I was tempted to put the writing off for a few minutes, then a few hours, then until the following day. I felt guilty that I wasn’t being more productive and that my chances of producing a quality piece of work were slimming by the minute.

But was that pressure I felt to perform such a bad thing? Will Felps, Associate Professor at UNSW Business School, says the feeling could have its benefits, in the right scenarios.

“Productivity guilt often provides a useful motivational ‘kick in the pants’,” he says. “While feeling guilty about productivity doesn’t feel good, it [sometimes] helps us motivate ourselves to get things done for colleagues we care about.”

Felps stresses the importance of distinguishing between productivity guilt and productivity shame, as HRM previously explored.

“Productivity shame is typically not healthy,” says Felps. “It is demotivating and typically leads to greater procrastination. Productivity shame makes us want to hide under the covers.”

Ringing any bells?

“You have to prioritise what really matters, and then let the rest go without feeling bad about it. You have to be the one to say, ‘That’s enough for today’.” – Associate Professor Will Felps, University of New South Wales

So productivity guilt can sometimes act as a reminder of what we should be doing, while productivity shame goes one step further, making us feel bad for not being more productive or doing more to support our colleagues.

It is key, therefore, to recognise the difference between the two and which one you’re experiencing.

Madeleine Dore, author of I Didn’t Do The Thing Today, a book about productivity guilt, says the issue is less the individual’s responsibility to solve and more so a systemic problem.

“Productivity guilt becomes a negative feedback loop,” she says. “Instead of recognising we’re in a system full of false promises that sets us up to fail, we place the blame wholly on ourselves.

“We try and fail and try again to live up to the pressures and demands placed on our days, and when we inevitably don’t meet society’s expectations – or our own – we can feel a sense of guilt, shame and anxiety.”

The adrenaline starts to wear off

Think back to pre-pandemic days, if that’s even possible. Were employees at your organisation feeling overwhelmed by their workloads or guilty due to their lack of productivity? If so, imagine how those feelings could have skyrocketed in recent years.

The pandemic has exposed the extent to which employees and and employers buy into the ‘always on’ culture – a phenomenon known as availability creep – and much has been said about the pandemic’s impact on cognitive function and burnout.

Now, as disruptions to the way we work are beginning to settle down, and more Australians return to the workplace, it’s likely that many employees are struggling to maintain the fast-paced workload they were forced to adopt at the start of the pandemic. They’ve been running on adrenaline for years now, and when you’re used to working at 120 per cent, working at 100 per cent can feel like failure.

“The fact that you could virtually always be working leads some people to feel like they should always be working,” says Felps.

“When you work from home … there’s much more flexibility about when you accomplish work tasks. But this flexibility is a double-edged sword. There’s nothing stopping you and your colleagues from working late until the night.”

Not only are our usual boundaries being tested, we’re realising our ambitious goals might not have been achievable even prior to the pandemic.

“The pandemic shook up our days in varying ways, but one thing it taught many of us is that we are more adrift than we think,” says Dore.

“When we don’t meet the high standard of productivity we set for ourselves, we feel bad – overlooking the fact that the benchmark was out of reach to begin with.”

Find a happy medium

So what’s the solution?

It’s clear that there’s no easy fix to productivity guilt, but there may not be any requirement to ‘fix’ it in the first place.

Instead, we could try shifting the emphasis we place on productivity, says Dore.

“We can untether [ourselves] from the idea that productivity is the sole measure of our worth,” she says. “We can forgive and accept the stumbles, and look at taking productivity off its pedestal and broaden the measure of a day.”

For example, perhaps we measure a successful day by how many people we had good connections with, how well we prepared ourselves to be productive in the future (e.g. diving into some research, setting up meetings or building a strategy to better manage our time), or simply how much we enjoyed, rather than judged, ourselves.

The overload of performance anxiety placed upon employees needs to change too.

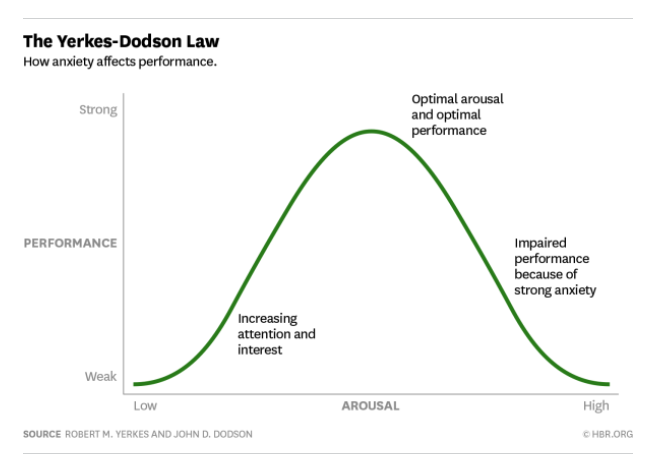

The Yerkes-Dodson Law holds that, to a certain point, as the pressure placed on an individual to perform increases, their performance grows at a commensurate rate – but after a point, their productivity drops significantly due to overload of anxiety.

“Managers want their followers to feel some productivity guilt, but not so much that it is overwhelming,” says Felps. “This relates to the concept of the ‘zone of productive stress’, also called the Yerkes-Dodson Law.”

Another way to think about it is stretching employees to improve without pushing them beyond their limits. Setting ‘stretch goals’ is a fantastic way to facilitate growth. Sometimes you need to let employees feel a little stressed so they learn how to problem solve and come up with creative solutions to the challenges they face, a concept HRM discussed with Harvard’s Amy Edmondson last year.

Felps is especially practical about what’s required to stay on the Yerkes-Dodson scale’s upper incline.

“Realise that you’ll never get it all done,” he says. “You have to prioritise what really matters, and then let the rest go without feeling bad about it. You have to be the one to say, ‘That’s enough for today.’

“Strategise about what you’re going to stop doing, to make time for what you think is really important.”

Dore’s approach goes even further: to deal with productivity guilt, she recommends recognising the “a slow process of untethering” from the system rather than depend on fast and easy fixes.

“What’s more realistic … is to recognise that work and life is a balancing act,” says Dore. “Instead of striving for stability, we can embrace what I call the ‘wobble’ – rather than striving for a life of perfect order, we can wobble between those tasks and commitments that are most meaningful, pressing or simply desirable in each moment.”

Many of us are unable to tear ourselves away from our ever-expanding to-do lists entirely, but taking small steps to improve employees’ wellbeing, and your own, can only have a positive impact on an organisation more broadly.

“We can swap being self-critical for being self-reflective,” says Dore. “Instead of lamenting that we didn’t get through our to-do list … [identify] whether perhaps we put too much on the to-do list in the first place, or whether we really need to do the thing after all.”

A healthy dollop of self-forgiveness, it seems, goes a long way to boosting an individual’s motivation and performance, which, in a workplace context, makes everyone happier.

It’s more important than ever to optimise your team’s productivity. AHRI’s Performance Management short course outlines the process required to effectively manage the performance of employees. Register here.

repeated words–The pandemic has exposed the extent to which employees and “and” employers