The pendulum has been swinging towards newer forms of performance management for years now. Has the upheaval caused by COVID-19 accelerated the process?

It’s time for a performance management revolution.

That’s what Dr Anna Tavis, Clinical Associate Professor and Academic Director of Human Capital Management Department at New York University, and Peter Cappelli, HRM academic, proposed in a 2016 article for the Harvard Business Review.

In the following years, Emma Grogan, Partner at PwC, recalls many organisations announcing they would throw out performance ratings altogether.

This didn’t happen to the full extent that many headlines predicted, says Grogan, but there was movement towards alternative forms of performance management that broke away from the more traditional approach – that is, an annual appraisal that reviewed past performance and outcomes.

History of performance management

Movement away from traditional forms of performance management in recent years hasn’t happened in a vacuum; there were major shifts for decades before, harking all the way back to World War I when performance management first began.

The emergence of newer forms of performance management can be attributed to two main factors, says Grogan:

In 2015, Grogan co-authored research which found that 42 per cent of employees in ASX-150 companies anticipated there would be no impact if performance management was ditched, and 35 per cent said it had no impact on their engagement or motivation.

“There was a feeling that performance management had been quite ineffective and wasn’t a process that supported employees’ development,” she says.

Employees have now shifted their expectations and are seeking learning and development opportunities.

“I think performance management systems need to change because they are going to be a differentiator for employers.

“Part of the value proposition that employers are looking to win on is saying, ‘If you come and work with us, we will grow your career.’”

An impetus for change

As remote working has become more widespread, many employers have had to rely upon different metrics.

“Leaders are now focusing more on outputs because that’s what they have to measure employees’ contributions by,” says Grogan.

COVID-19 has also created a need for more frequent touchpoints.

“Leaders are checking in more often, providing feedback through video-conferencing, or through digital feedback apps. We’re seeing a change of focus of those conversations to always include that check-in around mental health and wellbeing.”

Seeking to explore how performance management has shifted, AHRI teamed up with the University of Sydney Business School to survey 163 HR professionals in May last year (you can view the report here).

While the results were mixed, and many employers remained wedded to traditional approaches by default, COVID-19 ignited huge changes for some organisations.

John Shields, lead researcher and Professor of HRM and Organisational Studies at the University of Sydney Business School, along with co-researchers Associate Professor Sughoon Kim and Dr Anjali Chhetri, found not-for-profits (NFPs) are often a driving force in the uptake of newer performance management methods.

One NFP in particular is revolutionising its approach to performance management.

“Animals Australia is aggressively experimental, despite being a relatively small organisation. It is pushing the envelope in terms of practice change, and using COVID as fuel for that,” says Shields.

New ground for performance management

Before the pandemic, Animals Australia adopted a relatively conventional approach to performance management.

Kaylene Idda, its People and Culture Manager, describes it as “task-focused”, which included a standard personal development plan for each employee and operated on an annual cycle with a mid-year review.

When COVID-19 hit, they underwent a cultural transformation that placed flexibility as a central pillar.

Two themes sit at the centre of its performance management revolution, says Idda:

With a focus on flexibility, employees craft their personal and professional goals.

“Instead of being a tick-box exercise, it has turned into something that’s meaningful. It has challenged our people because [the performance management approach includes] questions that prompt self-reflection,” says Idda.

The approach pushes individuals to consider their purpose beyond Animals Australia.

“It’s about finding their meaning and purpose in life so we can identify how to help them get that within their current role.”

Blended approach

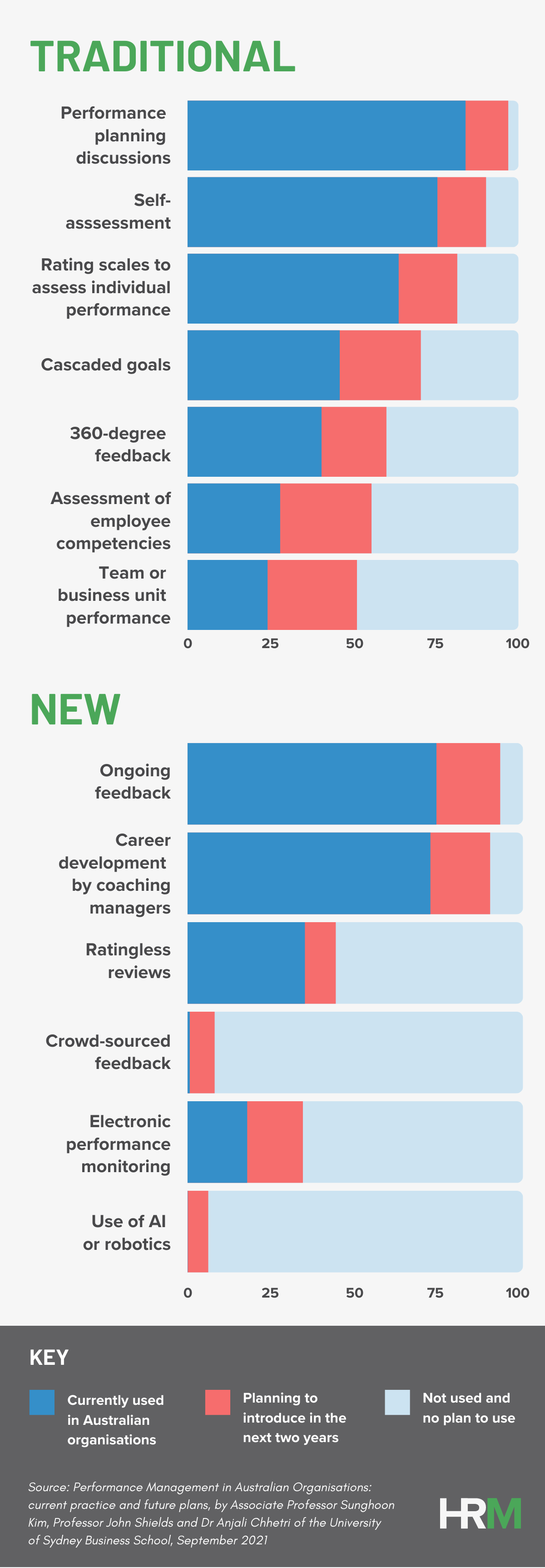

While Animals Australia is just one example, AHRI and USYD’s study suggests the willingness of a NFP to take up newer performance management approaches isn’t an anomaly.

“Big organisations, particularly for-profits, tend to predominate in the use of traditional practices,” says Shields. “They certainly aren’t ahead of the pack when it comes to newer practices, such as ratingless reviews, crowd-sourced feedback and ongoing feedback.

“In those newer practices, not-for-profits are every bit as proactive, and in some cases more.”

While there is movement towards the adoption of newer forms of performance management, many organisations are hesitant to shift from older methods.

In AHRI and USYD’s study, more than 70 per cent of HR professionals said their organisations were continuing to use traditional practices such as performance planning discussions and self-assessments.

However, it’s possible to have the best of both worlds by tweaking elements of a conventional approach and introducing newer methods where appropriate.

Even if an organisation isn’t seeking to revolutionise its performance management system, Grogan advises starting with a blank slate so you aren’t bringing any preconceived ideas to the table.

“At the end of the day, a lot of the features of traditional performance systems are still key decision points. Almost every organisation is focused around annual reporting periods, and so ultimately, targets and expectations will be set over the course of a year.”

An adherence to traditional methods, but with a newer take, has also been observed in the area of ratings.

“There is still going to be a need and desire by employees for direct and transparent feedback about how they’re performing,” says Grogan.

Doing away with rating reviews in a bid to create greater democratisation is a tempting prospect, but it can make it harder for a company to justify certain decisions.

“When there is an annual bonus, which there commonly is for listed companies, they want an explanation about why the company has made that outcome.

“That’s very difficult to explain when you don’t have some kind of rating or anchor point to attach people to.”

Where change occurs, however, is in the range of inputs the employer considers before arriving at a number.

When reviewing an employee’s performance, a manager might take feedback from clients, customers and an employee’s team members into account.

The success of implementing any new performance management method will depend on the organisational context and willingness to embrace change.

“Companies are facing a lot of choices right now,” says Tavis. “It’s not just the decisions they make about performance management, but also how they introduce it to the organisation and how much leadership support there is.”

Creating a change, however great or small, requires all moving parts to come together.

“The successful implementation of new performance management systems are usually about, not just what’s being introduced, but how they were developed, and what kind of leadership support they received.”

Strengthen your performance management approach and help your teams to excel with AHRI’s short course on Performance Management. Book in for the next course on 19 September.

Great topic and very relevant to performance management today. Would love to see more articles along these lines.

No, COVID-19 has not changed performance management for good. As Sophie’s identifies, it has been changing for over 100 years and will continue to change. To me, a key question all organisations should ask is “what goals do we want our performance management system to achieve? Animals Australia are very clear. I’d suggest 99% of companies are not. Even in her article, Sophie talks about goals including employee development, checking in, engagement, motivation, feedback, improving performance, and bonuses. My experience indicates if you try to achieve all these goals in one system you will fail. HR Practitioners need to help… Read more »

In the context of HR functions, PM is indeed one that attracts a lot of interest from all stakeholders. Recently we have seen a shift or a change in the name of one of the CIVHR units from Performance management to Performance Development. The content hasn’t changed substantially though. It appears to be an alignment with the push or notion of Performance Development which is gaining currency.

The key is to move to a far more empowered approach with mutil-directional feedback. Removing reviews leaves a vacuum. What follows? The other point here is that the terms performance management and performance review are not synonymous,

Performance management also includes, counselling, mentoring, disciplining and absence management to name a few.

At the end of the day we must move away from the tick and flick approach of the past – and present?