Asana’s latest Anatomy of Work Index shines a light on the bottom-line value of effective collaboration. But how can you change up your approach to reap the rewards?

Effective collaboration has nothing to do with where you show up to work, it’s all about how you show up. As organisations continue honing their hybrid work practices, this is a concept they need all their people to get on board with.

If your company continues to assume that every project needs to start with a meeting, or that we can simply copy and paste in-person brainstorming techniques to a virtual world, it’s likely that you will be surpassed by organisations that choose to do things differently.

It’s also possible that you could miss out on the bottom-line benefits.

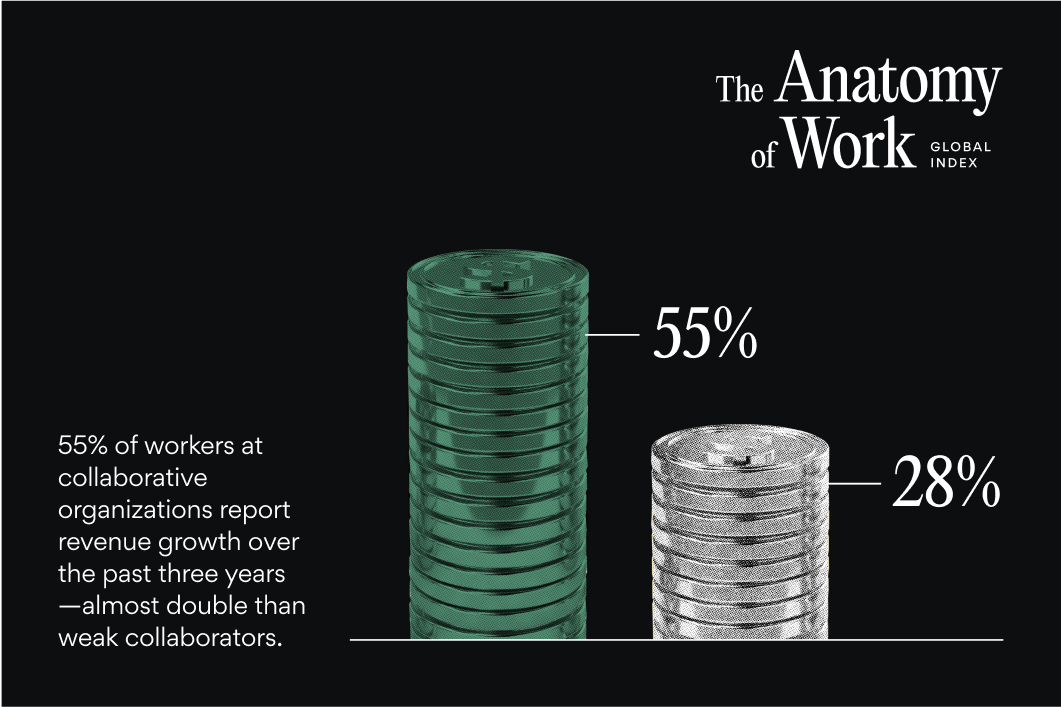

Organisations with strong collaboration cultures are more likely to report higher revenue growth, according to Asana’s 2023 Anatomy of Work Global Index, which surveyed nearly 10,000 global knowledge workers.

Fifty-five per cent of collaborative organisations reported revenue growth over the last three years – almost twice as many as organisations with weak collaboration cultures (28 per cent).

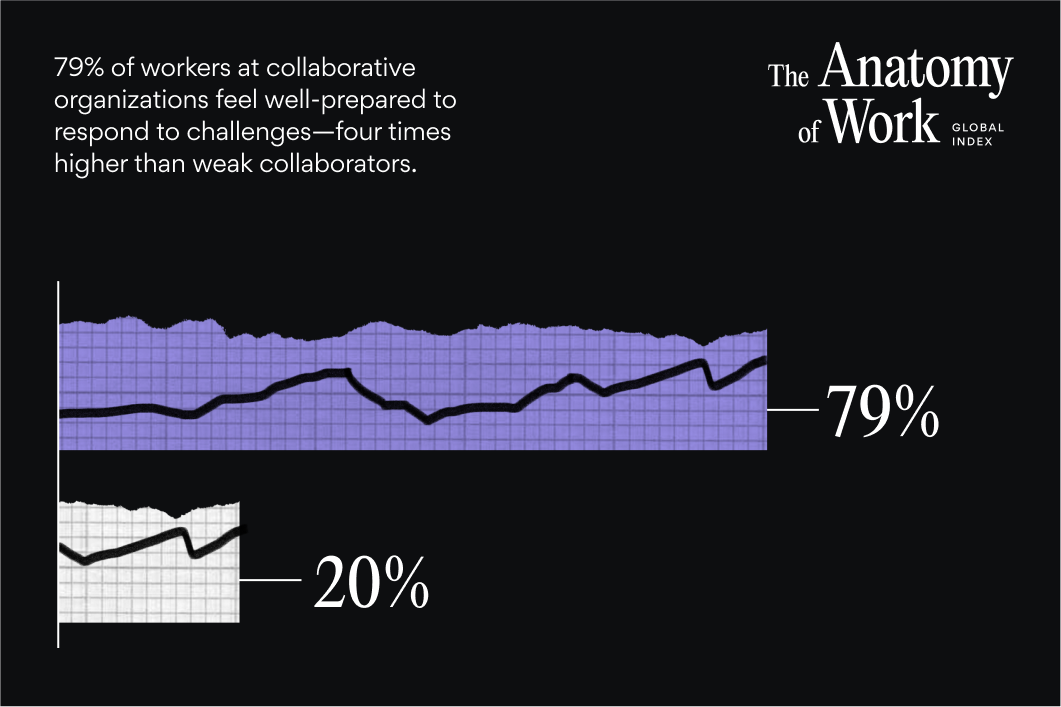

High-collaboration cultures were also significantly more likely (79 per cent) to feel prepared to respond to business challenges than laggard organisations (20 per cent). And 92 per cent of organisations with cross-functional collaboration felt they were contributing valuable work (compared to 50 per cent for laggards), which is likely to boost engagement and motivation among teams.

Collaboration fit for 2023

So that’s the ‘why’ factor, but what about the ‘how’ factor? To learn more about changing up collaboration practices, HRM spoke with Rebecca Hinds, Head of Asana’s Work Innovation Lab, which was founded in May 2022.

“[The lab] brings a level of rigour to our research, and varying perspectives,” says Hinds. “There can be a disconnect between academic research and what happens on the ground in real organisations, so [I’m excited] to bridge that gap.”

Earlier on, the think tank, in partnership with 19 academics – including Adam Grant, Wharton organisational psychologist; Liz Gerber, Associate Professor at NorthWestern; and Bob Sutton, Professor of Management Science at Stanford – released 12 predictions about how collaboration will change in 2023. HRM spoke with Hinds about five of them.

1. Creative collisions and intentional pairing

This first prediction came from Adam Grant. He said due to the siloed nature of work during those early pandemic years, managers would need to be far more intentional with connecting people with each other. One way to do this is through what he calls ‘creative collisions’.

“Workers today are more physically distant than they’ve ever been before,” says Hinds. “And that means that they’re less likely to bump into each other in the hallway.

“We know from research that a lot of the most creative ideas happen when you have people across different disciplines coming together across different functions for these creative collisions… people who aren’t on the same team and who wouldn’t normally see each other in formal work-related meetings.”

While manufacturing creative collisions might seem unnatural, it’s an incredibly important thing to consider if you want innovation and creativity to flourish.

“If you look at the research on creativity, a lot of it shows that the most creative outcomes happen when… there’s some intentionality around it.”

Hinds suggests trying the following:

- Pairing people in an intentional way across different functions to add “a sense of randomness” to their interactions. There are plenty of technology platforms that can help you do this, says Hinds.

Read HRM’s article on a new way to approach team building.

- Create opportunities for people to collaborate around shared interests outside of work – “If you pair people based on a love of music or a hobby, you’re more likely to manufacture these creative collisions by cutting across the formal organisational structures.”

“I think companies that just let it happen without any intentionality or added structure will see a weakening of [employees’] external networks.

“The companies that are really intentional about recognising the risks to networks with the shift to remote or hybrid work are going to come out on top, because it’s going to be an intentional redesign of how work happens.”

2. Creating diverse networks

If you’re engaging with the same people all the time to get work done, you could end up in an echo chamber, reinforcing each other’s ideas and biases.

In some instances, people might want to zero in on the most ‘qualified’ collaborators in order to get work done quickly, says Hinds.

“But I do think there’s a risk of over-emphasising efficiency, and purely identifying the most qualified people to work with. There are ways you can shortcut decision-making; there are ways you can shortcut brainstorming, but there’s a time and a place for that.”

Hinds says we need to think holistically about the people we’re collaborating with and “find people who energise us or fuel our creative juices”.

“We should be measuring collaboration just as judiciously as we’re measuring budgets or financial metrics; we should be taking a data-driven approach.” – Rebecca Hinds, Head of Asana’s Work Innovation Lab

The creativity-versus-efficiency argument is essentially the difference between collaborating and coordinating, she says.

“Collaboration is much more expensive than coordination. It’s pretty easy to transfer information and coordinate your work, it’s much more challenging to truly collaborate with another person and create something new out of that interaction or engagement.

“So it’s really about thinking, where do we want to optimise for efficiency, which would lean on coordination, versus where do we really want to create new ideas, which is more about collaboration.”

3. Reducing stress with ‘collaborative intelligence’

Rob Cross, professor of Global Leadership at Babson College and Co-founder and Director of Connected Commons says it’s important that organisations don’t increase employee stress by overwhelming them with too much collaboration.

His prediction was that employers will use ‘collaborative intelligence’ to prevent burnout in employees.

“[Collaborative intelligence] is essentially giving organisations information about how their workers are collaborating,” says Hinds.

“We know that over the past decade, the amount of time that workers spend collaborating has increased by 50 per cent. So workers are collaboratively overloaded. And it’s very difficult for them to understand what their top priorities are.

“Collaborative intelligence is about giving employees, teams and organisations more information about how overloaded their workers are, where silos exist within the organisation, where too much collaboration is happening, where not enough collaboration is happening, and really allowing us to start to measure and dissect this activity that consumes so much of our time.

“We should be measuring collaboration just as judiciously as we’re measuring budgets or financial metrics; we should be taking a data-driven approach.”

Priority overload is also another huge challenge for the modern-day worker. All requests feel urgent, which perpetuates cultures of hyperproductivity and can lead to burnout.

“I don’t think businesses in general have found a solution to this. I think this is something we’re going to see become more of a focus,” says Hinds.

The Innovation Lab ran an experiment to learn more about this. They built participants a collaborative intelligence dashboard that gave them daily metrics about their collaboration with colleagues and vice versa.

“We had participants look at their dashboard every morning, and also set three to five daily priorities. And we saw that the combination of being intentional about setting daily priorities, and also having the collaborative intelligence to understand just how much they were collaborating, triggered changes in their work behaviour.”

This included fewer notifications sent to their colleagues – i.e., not bugging them every few minutes with a Slack message or email.

“They became more aware of how their work impacts other people. Part of the solution is more awareness around whether we’re at risk of priority overload and [the cost of distracting colleagues].

Read HRM’s article on how to combat attention residue.

4. Using small nudges

In the prediction report, Huggy Rao, Atholl McBean Professor of Organisational Behavior and HR at Stanford Graduate School of Business, shared an example of small changes companies can make to reduce collaboration overload.

AstraZeneca noticed a recurring issue where employees were using the ‘reply all’ button in email exchanges, which resulted in thousands of unwanted emails. To combat this, the healthcare company created an automated popup that was triggered when employees tried to reply all to a message with 25 or more recipients. This helped to reduce unnecessary communications and kept teams focused on the work that mattered.

There are lots of other tech-based nudges that companies can trial, Hinds adds.

“I’ve seen companies do this with meetings. Some of the calendar software can show you how much time employee’s are spending in meetings.”

If you see that employees are spending 60 per cent of their days in meetings, you might like to start a dialogue about giving staff permission to decline non-important meetings, or trialing meeting-free time chunks during the day.

Hinds also suggests creating a feedback portal for employees to use when they encounter inefficiencies and friction points during work. This information might be then fed into HR to action, she says.

Read HRM’s article about how to use nudge theory with employees.

5. Getting asynchronous collaboration right

We need to recognise that asynchronous working styles are a huge departure from what we’re used to, says Hinds.

“Where I see companies stumble in trying to adopt asynchronous communication is when they think it’s very similar to synchronous ways of work. They think they can just flip a switch and tell their workers to have fewer meetings and collaborate asynchronously.”

But we need to develop new processes, norms and routines, she says.

“One of the findings to come out of Jen Rhymer’s research, which is in the report, is that in order to truly work asynchronously, companies need to have a very strong documentation culture. Employees need to understand where they can go for information that doesn’t involve tapping someone on the shoulder.

“They need the confidence and clarity that there’s a single-source of truth for information and knowledge. Without that, they’ll feel the need to collaborate synchronously.”

Moving to an asynchronous communication culture also requires some patience during the teething stages.

“In the transition period, it’s going to be more efficient to just ping someone or tap them on the shoulder if you’re co-located, but we need to recognise that if we want to shift this culture around communication to asynchronous, there’s going to be a learning curve, there’s going to be inefficiencies and it will take time to see long-term benefits.”

Ensure your team is thinking and acting strategically at every stage of the employment lifecycle with this short course from AHRI.