Unpaid family and domestic violence (FDV) leave has become part of the National Employment Standards. So employers need to understand the entitlement and consider potentially fraught issues.

Any workplace could be employing an FDV victim. The Bureau of Statistics says that, of Australians aged over 15, one in six women and one in 16 men have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner. These numbers don’t include other forms of FDV.

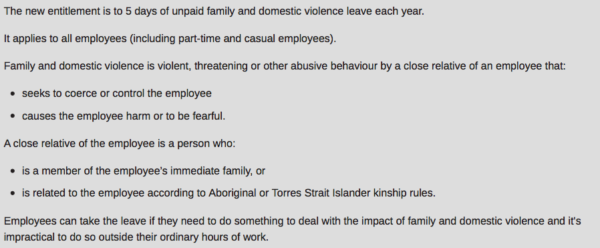

On 1 August 2018, five days of unpaid FDV leave was made an entitlement for all employees covered by modern awards and the government made it part of the National Employment Standards (NES) in December 2018.

Source: fairwork.gov.au

The ALP has signaled they want to take it further and match New Zealand’s 10 days paid FDV leave entitlement (which commences January 2019). Many public sector workers already have access to 10 days of paid FDV leave.

Helping not hindering

Dealing with applications for FDV leave requires compassion and sensitivity. Respect for privacy is critical to avoid making the situation worse.

Employers need people who have been trained to spot the signs of FDV and know how to help employees access their entitlements. Employers should provide training on:

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Accessing employee assistance programs and other avenues for help and assistance

- Developing objectivity and impartiality

- Maintaining professional distance and reliance

- Overcoming unconscious bias

Careful consideration needs to be given to how, and in what circumstances, confidentiality is maintained. There may be circumstances when information about an employee’s situation may need to be shared within the organisation. For example, if there are concerns regarding employee safety.

This should be done on a need-to-know basis and with the prior consent of the employee. Employees who disclose FDV should be advised how their information will be managed.

Record keeping is another issue. While FDV leave records will be “employee records” for the employee record exemption under the Privacy Act, these records should be managed in a similar way to other sensitive employee records. FDV records should be marked ‘confidential’, and access confined to authorised employees only – similar to information on grievances or disciplinary matters.

Also consider how FDV leave is recorded in payroll systems. If access can’t be restricted via a specific FDV leave payroll code, then consider manually recording information on a confidential file.

Employers must also recognise that employees experiencing FDV may not be in a position to immediately provide supporting documentation.

Other considerations

Employers covered by an award should ensure they understand the entitlement and put in place an FDV leave policy, setting out:

- What the entitlement is

- How the organisation will assist employees experiencing and/or disclosing FDV

- Who to talk to in the organisation

- How to apply for FDV leave, including how and by whom those applications will be managed

- Steps the employer will take to protect the privacy of employees and maintain confidentiality

- Whether any evidence will be required and, if so, what evidence (for example, documents issued by the police, a court, a registered health practitioner, a lawyer, an FDV support service)

Employers not covered by an award and who don’t have a formal FDV leave policy should be implementing one, given that the entitlement is part of the NES.

Finally, FDV leave is not the only way an employer can help those affected to feel safe and supported when they are at work. Perhaps the most important way to help is by recognising signs – not just obvious physical injuries, but other signs including arriving late, consistently calling in sick, and being distracted and unproductive at work.

Kylie Groves is a partner at Hall & Wilcox

Get an overview of HR-related policies and practices that support victims of domestic violence in Australian workplaces with AHRI’s Domestic Violence and HR Report (2017). Exclusive to AHRI members.

Would have been good to see an unhappy fella with his face blocked against that wall as the leading pic into this. Because using practical statistics (rather than those reported through “authority” chains) we know men suffer equally from the consequences of family/domestic (and community authority) abuse as do women. And please let’s call it Family/Domestic Abuse and not Family/Domestic Violence because THAT is misleading language. Kudos to author for acknowledging other forms in 2nd paragraph.

Family violence can impact lifetime earnings. Providing family violence leave and making sure that it is paid is a fundamental aspect of workplace support for victims.Thank you for sharing the information. The Voice of Woman