HRM looks at what the final report of the Royal Commission says about culture. Are we headed for a future where the HR responsibility is more heavily regulated?

Kenneth Hayne’s final report from the Royal Commission was released this week and a whole section is devoted to culture, which HR is often tasked with overseeing, and how it was linked with the risky, immoral and sometimes illegal activities of financial services entities.

Interestingly, it’s clear that Hayne has a problem familiar to many in HR. Since the global financial crisis there has been an agreement: we know culture is important, we know it influences every aspect of how a business performs (including staff misconduct), but our understanding of why and how is far from complete. Culture is still difficult to measure.

While Hayne’s actual recommendations around culture might not seem that far reaching – they’re mostly focussed on what the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) can do to have more effective oversight – they do point to a future where culture is not only clearly defined, it’s also regulated.

He writes: “Culture, governance and remuneration. Each of those words can provoke a torrent of clichés. Each can provoke serious debate about definition. But there is no other vocabulary available to discuss issues that lie at the centre of what has happened in Australia’s financial services entities and with which this Report must deal.”

No cultural ‘problems’

The report tackles the difference between cultures that are careless and those that are corrupt. For instance, was the act of aggressively trying to sell life insurance to a man with Down syndrome a case of a rogue employee who had too little oversight from management, or was it caused by a culture that encouraged profits above all else?

It would be nice to believe that it was industry-wide ignorance and a lax approach to risk that led to the need for a commission. But that’s not the case. For instance, the big four banks and AMP will pay a total of $850 million (and possibly more) for taking money for services that weren’t provided.

“It is necessary to keep steadily in mind that entities took money (a lot of money) from their customers for nothing. The conduct was so widespread that seeing it as no more than careless must be challenged,” writes Hayne.

In many instances it’s even inappropriate to say that financial service entities had cultural ‘problems’ because that phrasing implies mistakes were made. In fact, understanding that some actions were caused by a culture doing exactly what it was intended to do is crucial. You’re not going to cure something you haven’t correctly diagnosed.

The report breaks down its section on culture into three parts, so HRM will do the same, beginning with remuneration.

1. Remuneration

As Human Synergistics managing director Shaun McCarthy wrote for HRM, “Remuneration drives culture. Short-term incentives drive a culture of internal competition and a focus on short-term ‘wins’, rather than longer-term effectiveness.”

Haynes expresses a similar sentiment: “Poorly designed and implemented remuneration arrangements can increase the risk of misconduct. Well designed and implemented remuneration arrangements can play an important role in reducing that risk.”

Appropriately, it spends a lot of time on executive remuneration, both its design and implementation. It discusses how to best make sure that executive pay doesn’t encourage a focus on financial results (AHRI chairman Peter Wilson recently wrote a column on this topic).

More relevant to most HR professionals is what the report says about remuneration of front line staff. Hayne frames his thoughts on this area simply. “Focusing only on what is to be sold is not enough. How the employee does the job is at least as important as what the employee does.”

Hayne is biting about short-term variable remuneration systems in place. He refers to CBA’s CEO Matthew Comyn comments that the goal of their system was to elicit discretionary effort that would not be given were the remuneration fixed. “When the expression ‘discretionary effort’ is unpacked, it is evident that it is used as a euphemism for selling the bank’s products.”

The report tosses around the idea of removing variable remuneration entirely, and notes the testimony of ANZ CEO Shayne Elliott, who said his bank’s research showed that the most powerful tool to influence the conduct of staff is their manager’s influence over them.

Hayne says alternative systems that have fewer risks are to be preferred. (It is interesting to note that Hayne doesn’t really consider having executives paid out purely through fixed remuneration – probably because he knows it’s a non-starter.)

Hayne believes banks should adopt all the recommendations of the Retail Banking Remuneration Review written by Stephen Sedgwick, including capping any financial metrics at 33 per cent or less by 2020. Hayne insisted that the spirit of those recommendations be followed, not just the letter (nobody should try and hide financial metrics in ‘customer’ metrics).

But he insists this is a first step, and that banks must continually review their systems with reference to the ‘how’ of staff tasks and not just the ‘what’.

Andrew Linden and Warren Staples, lecturers from RMIT, have made the argument that Hayne has offered a “patchwork of measures” that will be eaten away over time because “the rationale for their adoption will be forgotten”. They predict another commission in 10-15 years.

The report refers to an ANZ experiment that hints at why short-term variable remuneration based on financial metrics might come back in vogue. By early 2017 the bank had done a 15-month trial where it removed individual sales-based incentives and replaced them with customer-based metrics in one of its retail banking districts. That district reported both improved customer satisfaction and good levels of employee engagement. But it also performed worse than average on sales.

A decade away from the spotlight of the Commission, that’s the kind of data that might persuade a return to bad habits.

2. Culture

The second section on culture is just called ‘culture’. It talks about efforts to assess and regulate culture that happened after the global financial crisis. And mentions APRA’s efforts to understand and regulate risk culture (a subsidiary concept of culture that focuses on risk).

That culture would face official regulation should fascinate HR. The report admits that this development is, “internationally, at an embryonic stage”, so what would it look like?

From Hayne’s point of view, culture may be hard to measure but behaviours and other cultural impacts aren’t. He recommends beginning with the work APRA did with its prudential report into CBA (released April 2018). Larger institutions regulated by APRA, including the big banks, were required to conduct self-assessments against what the report held.

But he wants more, and he wants APRA to have the resources to do it. “The work of the FSB, G30 and international practice more generally show that this work is essential to the proper prudential supervision of banks and, in my view, other large APRA‑regulated institutions”.

He specifically wants financial regulators to be able to:

- assess an entity’s culture;

- identify what is wrong with the culture;

- ‘hold up a mirror’ to the entity, and educate the entity about its own culture;

- agree what the entity will do to change its culture; and

- supervise the implementation of those steps.

This is another part of the report that’s interesting for what it doesn’t say. When it comes to how financial services entities should monitor their own culture, Hayne just refers to ANZ’s fairly boilerplate internal auditing.

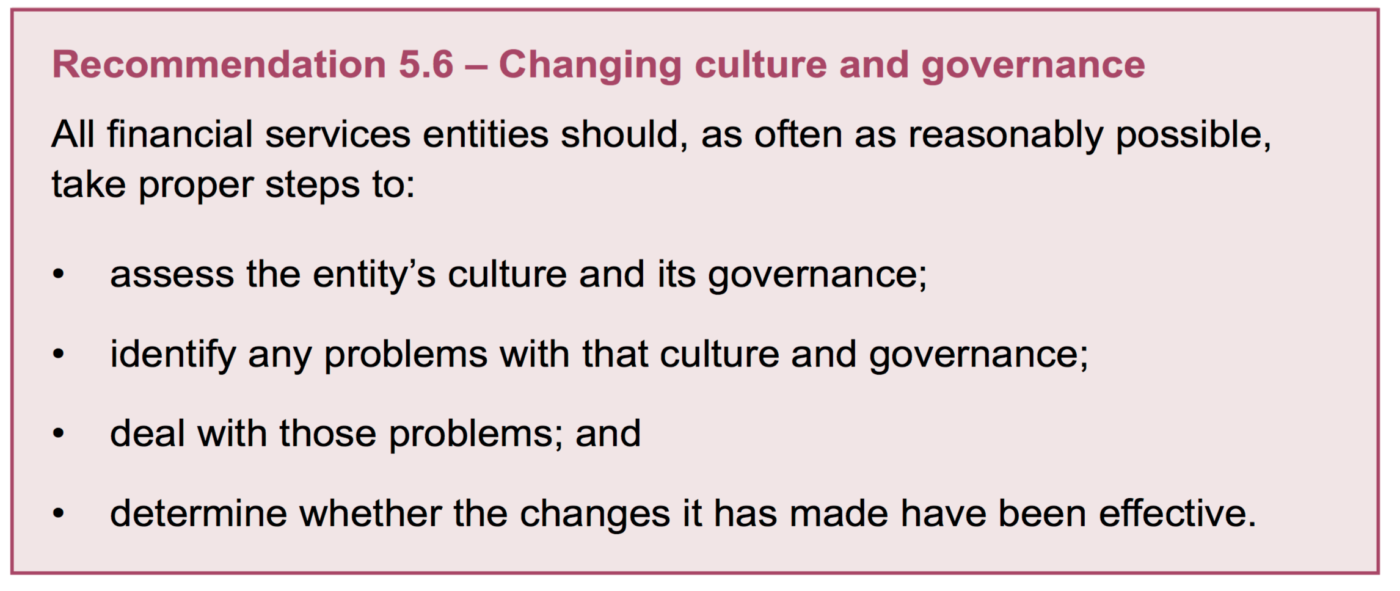

He also repeats standard ideas around culture, such as it being a continual process and not a one-off event, that leadership (both from the top and in management) is important, and that while culture can’t always be measured, its outcomes can be. His ultimate recommendation around internal cultural change is very general:

Haynes is aware this recommendation reads as quite general, and so stresses that it should not be taken lightly.

“What the Recommendation requires is much more than an exercise in ‘box‑ticking’. Its proper application demands intellectual drive, honesty and rigour. It demands thought, work and action informed by what has happened in the past, why it happened and what steps are now proposed to prevent its recurrence. Above all, it demands recognition that the primary responsibility for misconduct in the financial services industry lies with the entities concerned and with those who manage and control them: their boards and senior management.”

3. Governance

In the final section, Hayne writes about governance. He spends time on the role of boards in ensuring culture is a priority and focuses particularly on their oversight when it comes to risk culture.

It also touches on accountability, and the theory that “the problem of diffused responsibility and no clarity of accountability has been at the heart of many problems that have happened”. His recommendation for this is not that useful to organisations outside of financial services sector, as it’s mostly to do with the accountability that the enactment of the Banking Executive Accountability Regime (administered by APRA) will provide.

He also takes time to deconstruct the idea that a culture of profits above everything else originates in doing what is best for shareholders. He argues, “financial returns to shareholders will always be an important consideration but it is not the only matter to be considered”. He says that by thinking of the long-term viability of a company, the interests of all stakeholders (employees, leadership, customers, shareholders, etc) converge. And that is what a company’s directors, and the company in general, should focus on.

Non-financial risks

Hayne makes frequent reference to the need for financial services entities to focus on non-financial risks, and not only financial risks. In her recent op-ed about the Commission and HR, which appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald and other Fairfax publications, AHRI CEO Lyn Goodear referred to the same thing. “The term non-financial risk is another way of talking about the vagaries of human behaviour and the cultures that dictate how and why humans behave the way they do.”

Those vagaries have never been more important to businesses it seems. That culture is specifically labeled by Hayne as crucial to understanding the discoveries of the Royal Commission is something of a watershed moment. For the rest of the world, culture was thrust into the spotlight by the GFC but, because Australia missed the worst effects, it’s perhaps never been given the same priority.

But now some organisation’s cultures will be subject to regulatory scrutiny. It will be fascinating to see how that unfolds, and whether its impacts will reach beyond institutions subject to APRA regulation.

Organisations want the best of the best in HR to help make their culture sustainable. Getting certified can help you establish your expertise and set you apart. As Lyn Goodear wrote in her op-ed, “the certification pathways don’t just speak to knowledge and skill, they speak to character and behaviour.”

It’s all about ethics, leadership and demonstrable sanctions. Codes of conduct and ethical/probity rules are easy to identify, and I suspect the Banks already have them. It’s the actual education, implementation and monitoring that is so often missing. Our clients have all the policies, but I doubt if too many of them read them or think about them until things go wrong. The HR role? Leadership, Education and Training, monitoring and acting on breaches! Above all the leadership team from the CEO

[…] recent Royal Commission in to Banking and Finance highlighted the issues of a profit-driven culture and inadequate systems […]