How, why and where we work will look very different in the next 20-30 years. Experts paint us a picture of the future of work.

Fear of new technology is probably as old as technology itself. In 1825, some people believed if they travelled on the world’s first public steam railway, their skin would melt. Others thought limbs would be ripped off, or women would have their uteruses torn from their bodies. Such stories seem naively comical now.

And yet there’s every chance that in three or four generations, our great-great-grandchildren will be laughing at us for thinking automation would put an end to human employment. If they could speak to us, they might say the future of work is not dire, but exciting.

But they might also tell us that it will not be without its challenges. Since we don’t have their benefit of retrospection (no-one seems to have developed time travel yet), HRM talks to current-day experts, who will be speaking at AHRI’s National Convention in a few weeks time, to get their predictions about the what, where, how and why of the future of work.

The work we’ll do

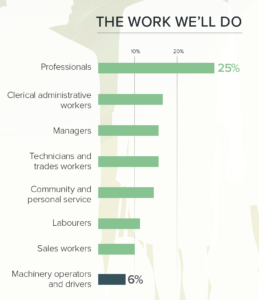

Advancements in technology mean we have long shifted focus away from the work of our hands. Knowledge work – the work of the head – has only become more important since it first boomed in the 1980s-90s. During that period, cognitive occupations increased at four times the pace of manual work in Australia.

This trend will only continue. A new report by Deloitte, The Path to Prosperity: Why the future of work is human – the seventh instalment in its ‘Building the Lucky Country’ series – suggests that 86 per cent of jobs in 2030 will be for knowledge workers.

And there’s another change on the horizon. A rise in the jobs that are hardest to automate: work of the heart. This is work that combines both the head and hands, and includes jobs that revolve around creative thinking and interpersonal relationships. Worryingly, it seems we’re less prepared for this shift.

Australian employers need one million more people with digital literacy skills than are currently available, and five million more with customer service skills. These numbers are expected to grow as automation takes on more hand work and humans move into jobs that centralise core skills.

So how do employees and employers feel about these changes? According to LinkedIn’s Future of Skills 2019 report, 39 per cent of Australian employees say they are daunted by the pace of change in their industries. Nearly 50 per cent of employers had the same fear, and they feel their staff currently don’t possess the necessary skills to keep up.

The report also found that 46 per cent of Australians are motivated to upskill in order to prepare for the future of work, with 41 per cent keen to do so in order to fast-track their career and 29 per cent due to fear of being made redundant.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Deloitte’s report shows that five million more Australians are employed today than in 1988 (7.2 million to 12.8 million) and that unemployment rates are decreasing.

It also indicates that the future will be female. Men currently dominate the market for manual work, but these industries are most likely to see job cuts. Women, on the other hand, make up 56 per cent of non-routine work of the head, which is predicted to be the fastest-growing type of work.

What work will look like

The future as depicted in movies from a half-century ago has become laughably kitsch. You know the aesthetic. People are clad in foil and speaking into thumb microchips as they hoverboard towards work. But some experts say this might not be too far from the truth.

Dr Fiona Kerr, founder of The NeuroTech Institute and expert on the impacts of technologisation, has a few interesting predictions.

“We already have things like the ‘smart workplace rice grain’ that we’re now seeing in Scandinavian countries. It’s a microchip that you put in under your skin, in the wedge between your finger and thumb,” she says.

“This allows you to go about living in a smart city/workplace. It will turn your lights on and off, it will do your photocopying. You can wander into the cafe and it already knows you’re there. It knows what you pick up and it pays for it as you walk out. If someone at work is looking for you, they can look you up on a system and see that you’re on level three,” says Kerr.

Wearable technologies (not embedded) are already becoming prevalent in workplaces. They are often used for monitoring and collecting people analytics. And it’s not just the Apple Watch.

Researchers are developing glasses that effectively read your mind by assessing your eye movements and measuring your brainwaves. And some wearable tech is much bigger than a pair of shades. For those who will still engage in work of the hands, exoskeletons are being trialled to assist in picking up heavy items and allow people to endure long periods of standing.

“Though less physically invasive than an implant, wearable technology is having a growing impact on physical health which can be positive or negative, depending on how it’s used,” says Kerr.

“While it can increase safety and productivity, it also has the potential to increase stress levels and depression. Thought needs to go into how we deploy such technology and its effect on the wearer’s neurophysiology.”

Physical changes

If you think embeddable and wearable technology will result in the demise of the physical work office, Deloitte is here to say you’re wrong.

“Only one in 25 staff worked remotely on the day of the last census, even though almost one in five employers now offer the ability for staff to work from home. People are seeing benefits from being together in terms of their productivity and being able to do their jobs,” says David Rumbens, a partner at Deloitte.

Esteemed academic and author Professor Stewart Friedman says we’ll still value face-to-face time with our colleagues, but home may well be where most work gets done.

“The boundaries between work and other parts of life will be built and modified, more by individuals customising their work time and place than by administrators and managers.”

Rumbens predicts the solution to the isolation of four-walled offices and the distractions of open-plan workplaces will be melding the two ideas together.

Kerr says office walls of the future will be able to alternate between opaque and clear, and that touch screens could appear on them when required. But she also believes we’ll see the creation of dedicated low-tech spaces.

“We need to design spaces for reflection or to be in nature. Our brains are working in an elaborate and extrapolative way when we’re staring out of a window.” – Dr Fiona Kerr

“In order for the brain to go into a state called abstraction – when you are truly creative and have those ‘A-ha!’ moments – you have to turn technology off because it distracts you in all kinds of cognitive ways. We need to design spaces for reflection or to be in nature. Our brains are working in an elaborate and extrapolative way when we’re staring out of a window,” says Kerr.

There are real risks to all this new technology. Any door that can unlock and open for you is also capable of closing and locking you in. We can never truly understand the future impacts, negative and positive, of technology. We can only speculate.

“We don’t know how to minimise the drawbacks across an organisation or industry, as many of them are yet to emerge,” says Kerr. “We don’t know how to build tacit learning that allows us to gain human interaction by partnering with artificial intelligence [AI]. We don’t think about the cognitive fatigue that comes with technologisation.”

Immersing ourselves too deeply in new technologies will have an impact on our humanness. Using virtual reality as an example, Kerr says while some people fantasise about being able to stay at home and send an avatar to work, cognitively we won’t be capable of doing something like that.

“After a while, the cognitive fatigue from the excitation of an immersive environment and medium means that we are basically dumb as a box of hammers. We can no longer see complex problems in the same way.

“There are a lot of aspects around creativity, adaptivity and complex thinking that get minimised when you interact too much with the technology and are hugely maximised when you create those chemical changes in the brain that come from face-to-face interactions.”

Kerr says we need to start thinking about AI as a “goal-driven optimiser”, humans as the creative extrapolator, and how, when and if they partner.

“Some people just go with the next bright and shiny thing. That’s not the way to do it. I turn it around and start by first deciding if it’s something that needs to be technologised in the first place.”

Learn more from those interviewed in this article at AHRI’s National Convention and Exhibition. Registration closes today, so make sure you secure your spot and learn from some of the best.

The people difference

The essence of where we’ll work isn’t just about the bricks and mortar of an office. The culture and diversity of that space matters too – maybe even more so. Susan Scott-Parker, disability advocate and founding CEO of business disability international, says only a portion of the responsibility of bringing diversity to work lies with HR. She calls on chief operating officers to take more ownership of these matters because many of the barriers for staff living with a disability are operational.

To combat them, Scott-Parker suggests the creation of different roles, such as a chief productivity officer. “Their job would be to coordinate the business process that kicks in when someone says, ‘Those lights give me migraines.’ At the moment occupational health professionals are on a contract that doesn’t refer to how they should react to disability. And the contract with the facilities manager doesn’t say who pays for the lights, who agrees which lights to get, who orders them, who chases them up when they don’t turn up on time, etc.

“I know a large public body where it routinely takes eight months to deliver the software that a visually impaired person needs, where other organisations would have it within 24 hours because they have a pre-approved catalogue of assisted devices. You just order it and it’s with you the next day.”

Scott-Parker says there’s also a need for the creation of a workplace adjustment practitioner – someone who can facilitate these changes – and for those organisations that already have a role like this, it makes “a huge difference”.

How we’ll work

Australia’s current approach to work and learning might be hamstringing us, says Rumbens.

“We still do the bulk of our learning in and immediately after school, and then move onto the earning phase. That’s not so appropriate in today’s workforce where skill needs are changing rapidly.

“Universities will be increasingly looking to get into the microcredential space. They don’t just want to be the organisations that handle young people leaving school. They want to act as a bridge between school and the workforce. They’ll be the organisations handling ongoing lifelong learning needs.”

If businesses and managers start making the right choices now, Australia’s annual economic welfare could be boosted by $36 billion by 2030, according to Deloitte. Rumbens breaks down these ‘right choices’ into three categories: increasing workplace participation rates by making work more flexible; reducing the cost of absenteeism and presenteeism by decreasing workplace stress; and changing the skills mix.

Many organisations already foster flexible, low-stress workplaces, but the final point is new territory. Attracting and retaining top workers has always been high on HR’s agenda, but never before have those charged with hiring and training had to keep up with such a rapidly shifting landscape.

Self-employment myth

While the rise of the gig economy can’t be ignored, the self-employment rate has actually been on a consistent decline since the mid-1970s and currently sits at an all-time low.

“People find it surprising because of the rise of Uber and the like. But what we don’t see is that self-employment is reducing in other parts of the economy,” says Rumbens. “In the construction industry, for example, people used to work for themselves a lot more. Now we’ve seen a consolidation. The same could be said for smaller retail stores.”

Deloitte’s report also shows that Australia has a higher proportion of part-time workers than most developed nations, and that three-quarters of those workers say they don’t want to take on any more hours. While many employees might be pursuing part-time roles in an effort to manage their work/life balance, the desire for a portfolio-style career could also be a factor.

Rob Phipps FCPHR, managing director for Evolvefast and AHRI’s NSW state president, says: “While portfolio careers are more common for those in the middle or towards the end of their careers, this style is actually well-suited to the emerging workforce – those who are seeking more flexibility, difference and development opportunities.”

Why we’ll work

So that’s the what, where and how – but what about the why? What’s going to motivate us? What do employers need to think about now?

More and more research indicates that, in certain cases, employees prefer flexible hours over higher remuneration.

According to Gartner, the three main attractions for Australian jobseekers are location, respect and work/life balance. Internationally, they are compensation, future opportunities and people management.

Clare Murphy FCPHR agrees flexibility will be a key driver for our workplace motivations, and says we’re effectively charting new territory.

“We’re the first generation of ‘career couples’ – moving away from the female having a job but still being the primary carer, to dual-career couples. That generation is really trying to work out, for the first time, how to make that balance work. Flexibility there is essential.”

Murphy says HR needs to help managers by giving them the skills to support staff who might not always be at their desks.

“It’s about HR teaching managers how to have the conversation about making flexibility work rather than how to say ‘no’ to it.”

Protecting the planet

When talking about the future of work, the conversation needs to include the matter of protecting the planet. Without serious action being taken to combat climate change, all predictions in this article could become completely redundant.

“In light of current climate science, the relationship between humanity and the natural environment will likely be the primary issue driving creative and productive efforts,” says Friedman.

“It’s daunting to try to envision what a work day will look like in 25 years and what the main motivators will be, but worth the effort because it helps us to clarify what we want it to look like now.

“People just expect transparency these days. The ‘need to know basis’ won’t wash anymore.”– Clare Murphy FCPHR

“People will be motivated to play a part in preserving our planet’s beauty, and power to nourish us. And as AI advances and more jobs of all sorts are done by non-humans, people will likely work fewer hours, compensation practices will need to adjust and we will have to rethink how we spend our time.”

Phipps suggests that employees’ sense of social purpose will soon match remuneration expectations. “People will be looking for organisations that can support them to fulfil their purpose and have a purpose that’s not just tied to the financial success in their organisation, but a purpose that can give back to the world in a positive way.”

He believes organisations should start actively thinking about their triple bottom-line. This model encourages a ‘people, profit, planet’ approach, meaning social and environmental concerns get treated with the same attention as profits.

Trust at the core

Climate change isn’t the only global workplace challenge. According to communications firm Edelman’s 2019 Trust Barometer, only one in five people feel ‘the system’ is working for them and over 70 per cent have both a sense of injustice and a desire for change. Interestingly, more people said they trusted their employer (75 per cent) than said they trusted business in general (56 per cent), the government (48 per cent) or the media (47 per cent).

Employers shouldn’t feel too secure. Following public reactions to #MeToo and other workplace scandals, staff are demanding a new approach to workplace culture – and this expectation impacts the bottom line. According to Edelman, 78 per cent of people felt that how a company treats its employees is one of the best indicators of its trustworthiness, and 67 per cent agreed that a company they don’t trust won’t get their money.

“People just expect transparency these days,” says Murphy. “The ‘need to know basis’ won’t wash anymore. The idea that you are going to trust your manager or your organisation just because they are in a position of authority is gone. Fundamentally, we have to build trust in HR. People have to trust that we’re doing the right things for the right reasons.”

Scott-Parker agrees. “It’s not just the general public having lack of trust in the profit-making corporations. I think there’s a breakdown of trust on the part of the employees that they’re actually valued and going to be treated properly and fairly.”

Trust is one of the most fundamental pillars of the future of work. We’ll need to trust in the technology we’re implementing; we’ll need to trust our staff to work flexibly and productively; and we’ll need to trust that our employers will have our best interests at heart.

So perhaps before we start implementing new technologies and shaping our culture around them, we should first seek to answer this question: How can we make sure that we really trust each other?

This article originally appeared in the September 2019 edition of HRM magazine.

Hear more from this year’s convention speakers by following HRM’s live blog hrmonline.com.au/nce/convention-2019 during the event.

In response to working in a VR environment. This is not fantasy. Kerr needs to observe teenagers as they will drive the future of work. Have you ever seen anything that will keep a team (in this case a team of online teenagers) completely engaged and immersed in strategizing for hours to improve performance and outcomes. This is happening now.