Is the proposed Victorian laws to severely punish leaders for workplace deaths and suicides just what we need or discriminatory?

The Victorian state government has proposed laws that could see employers in both the public and private sectors facing up to 20 years of jail time and $16.5 million in fines for certain workplace deaths.

The purpose of the proposed Victorian legislation, according the introduction bill, is to “reflect the severity of conduct that places life at risk in the workplace” and to “hold those with the power and recourse to improve safety to account”.

The proposed laws would also see employers liable for the deaths of workers caused by unsafe working environments, as well as the death of any members of the public due to workplace negligence.

It’s not just employers who encourage toxic work cultures – like bullying, hazing or harassment – that could be held to account for workplace suicides or manslaughter. The laws would also apply to those who fail to provide staff with adequate mental health support and safety.

It could happen here

HRM recently covered the news of the France Télécom executives who’ve been on trial for the suicides of 19 employees, the attempted suicide of 12 and the psychological harm experienced by eight others.

In that article, HRM noted that “there is almost no chance a similar trial could happen here” due to different court systems, differing laws, and so on. But this proposed legislation, along with the similar laws in Queensland and ACT, could push Australia closer towards what France has.

If passed, this legislation will build upon existing criminal laws around workplace bullying in Victoria known as ‘Brodie’s Law’, which was introduced in June 2011 and means that ‘serious bullying’ is punishable by 10 years in jail. While Brodie – whose death led to the law – faced bullying took place in a work environment, the law extends to bullying in all places: schools, community organisation and on the internet.

“This new law would be very threatening to many employers because it wouldn’t distinguish between those employers who try to do the right thing and those that don’t,” says Alan McDonald, the managing director at Melbourne-based employment law firm McDonald Murholme.

McDonald is an experienced workplace law professional, and he’s had clients who’ve taken their own lives following workplace bullying or harassment. But McDonald doesn’t think this legislation is the answer to the tragic workplace deaths in Australia.

“In the Victorian Occupational Health and Safety Act, there’s already very sound legislation to protect employees and regulate the conduct of employers. There’s also very strong provisions in the Fair Work Act which mandate that employers have a social conscience – meaning they will not discriminate against people, which can sometimes lead to anxiety or depression.

“The problem is that the Fair Work Act isn’t being taken seriously or accessed properly. Employers don’t appreciate the damage they can do to the employee by mistreating them in the workplace,” says McDonald.

High burden of proof

With high penalties on the table, the Victorian attorney general Jill Hennessy says there will be a high burden of proof to charge an employer under these new laws.

“The standard is very high because the penalty is very high,” Hennessy told The Age. “A person who has been brutalised when it comes to their mental health and wellbeing… The laws will apply to this.

“All workers deserve a safe workplace and the proposed laws send a clear message to employers that putting people’s lives at risk in the workplace will not be tolerated.”

According to the Victorian government, employers who are compliant with their WHS obligations need not worry, as they will not be found guilty for a “rogue” employee who acts out and dies as a consequence.

In prosecuting an employer, the bill says “the mere fact that an organisation’s or officer’s [anyone wielding power in an organisation] conduct contributed causally to the death, or was a necessary cause of it, is not sufficient. It must have ‘contributed significantly’ to the death or have been a ‘substantial and operating cause’.”

“It’s all well and good for Jill Hennesy to say we need the bar to be high, but it will still be very hard for people to decide [where the responsibility lies],” says McDonald.

“We need to focus on making the existing laws work, which don’t involve anyone going to jail, but which do involve penalties. It can be very hard to get these matters before the court and it’s very hard to get fines. We get hundreds of claims but very few get put through because there are so many obstacles that get in the way.

“There’s already really good stop bullying laws in place in the Fair Work Act and I don’t think we need more. In the hundreds and hundreds of cases that have been brought under the act, there has been very little progress in respect to Stop Bullying orders. The general outcome of these cases is either the claim is withdrawn or they recieve money to leave the workplace. So you might say that we should enforce that law in a more effective manner that will actually stop people from bullying others.”

A poisoned chalice

McDonald says the government’s laws could end up coming back to bite them.

“It’s the government departments that often take the most robust defences and play hard ball with their own employees when they try and use the social standards of the Fair Work Act. Is the government prepared to take responsibility for what goes on in its own departments?

“The client of mine who took their life was an employee of the Department of Human Services. If this law had been in place at the time it might have applied to the head of that department. Is that what this government wants to be responsible for? If the answer is ‘yes’, then it will end up prosecuting itself.”

McDonald doesn’t believe the government is very good at prosecuting itself.

“Look at various Royal Commissions or the recent Red Shirt scandal – they never prosecuted those politicians, they weren’t even interviewed. [The Government] use the massive resources of the big private law firms to defend themselves. By and large, smaller businesses in the private sector don’t have any of those resources. Therefore this law is inevitably discriminatory against those who cannot defend themselves.

“I think it’s one step too far to introduce a law like this, unless the Government is prepared to take the consequences and I don’t think they are.”

Size and industry matters

One of the criticisms of the new laws is that they don’t take into account the size or type of organisation where a workplace death could occur.

The nature of the legislation means bullying that takes place in a small to medium business (SME) is much easier to pin on someone than bullying that takes place in a large organisation. In smaller businesses, staff are more likely to interact with a greater proportion of their colleagues; the head of the company is likely to know the staff by name and to have some level of oversight into the dynamics at play.

So what happens if we’re talking about the CEO of a business with hundreds and thousands of staff? If someone lower down the organisational ladder takes their life, is the CEO responsible?

What if they’ve never met that person before? Should we not be looking to the individual’s manager or their co-worker – those who are more likely to impact an individual’s experience at work – for answers?

A statement from the Victorian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, one of the groups criticising the bill, says that due to the significant penalties being put on the table, “It’s vital the government gets this law right.

“We consider that the laws will disproportionately impact small business. Put simply, the operators of smaller enterprises are more likely to have a ‘hands on’ role in the business. Overseas experience has shown that they will likely bear the brunt of these laws.” .

The Chamber says the laws should be changed to encompass anyone who has “engaged in criminally negligent conduct resulting in death, not just organisations and senior officers” and calls for more education and training for those charged with managing these complex cases.

The Victorian Farmers Federation has also expressed concerns. Vice-president Emma Germano said it’s “incredibly worrying” that WorkSafe would be the investigating body in these cases, as she believes it doesn’t have the required skills, experience or resources. She is in favour of Victorian police handling such investigations.

Germano also said these laws would have a “disproportional and cruel impact on family farms and businesses.” Considering that many farmers are both employers and employees, as well as often being family members, she says laws like this could punish grieving families and traumatize them even more.

What’s going on in other states?

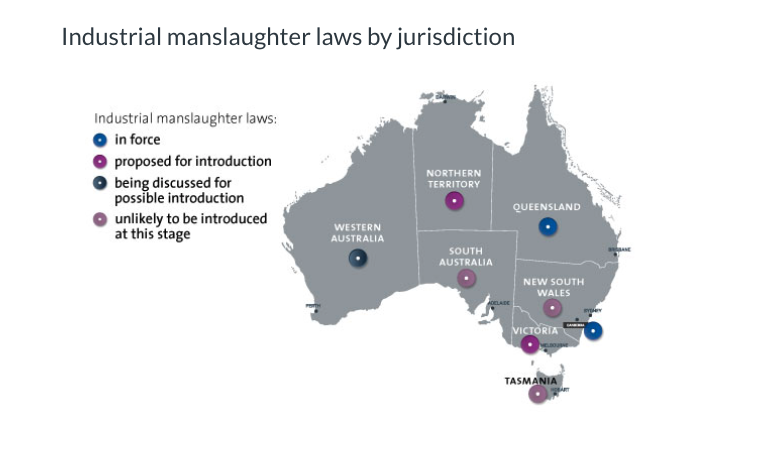

If these laws are passed, Victoria will be the third Australian state to criminalise workplace manslaughter, following in the steps of Queensland and the ACT.

In March 2004, the ACT became the first state to introduce industrial manslaughter laws. These were separate to their WHS laws, and sit instead under the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT). Although, according to the SMH, the ACT is looking to shift this legislation to sit within WHS laws. Currently, individuals face 20 year jail terms and maximum penalties of $320,000, and corporations face fines of $1.62 million.

Queensland included industrial manslaughter laws in its workplace health and safety law changes in October 2017, following the death of two workers who were crushed from a concrete slab at Eagle Farm Race course and the devastating Dreamworld ride failure which claimed the lives of four people. Maximum penalties in Queensland include 20 years’ imprisonment for individuals or $10 million fines for a body corporate.

Legislation around industrial manslaughter has been tabled for discussion in Western Australia and in the Northern Territory.

According to Ashurst law firm, no prosecutions have been made under the Queensland legislation at this stage and only one has been made in the ACT, which is still going through the courts.

Tasmania, New South Wales and South Australia aren’t making any moves towards criminalising workplace manslaughter at this stage. According to NSW Better Regulation Minister Kevin Anderson, it won’t be happening in NSW anytime soon, despite NSW having the most workplace deaths in 2017 (ACT had the fewest).

Anderson told the Sydney Morning Herald the laws in other states are little more than a “catchy title on paper” and said his government would instead take preventative measures. We shouldn’t have to wait until someone dies before action is taken.” .

McDonald agrees: “Prevention is better than cure. You don’t necessarily need this law. Let’s work on dealing with the current laws we’ve got.”

On a federal scale, the Coalition has expressed the view that national industrial manslaughter laws aren’t necessary.

More details around these proposed laws are expected to be announced by the Victorian Government’s Workplace Manslaughter Implementation Taskforce over the coming months.

If you require mental health assistance or information visit beyondblue.org.au, or call Lifeline on 131 114.

Managing workplace bullying is incredibly important. Ignition Training’s half day course Bullying and Harassment provides participants with the necessary knowledge regarding legal and duty of care obligations, how to identify bullying, harassment and workplace violence, and prevention tools.

There are well established practices in all States and Territories for the authority responsible for investigating potential safety breaches to follow. These practices include robust process to identify where “the buck stops” in regard to culpability. It not seem reasonable that Industrial Manslaughter laws would simply overlook this particular expertise. The second argument – that such laws would mean that government departments could be subject to the law, is probably the least effective argument against any legal change.

The only question is, do we need criminal penalties to improve Health and Safety compliance?