Living up to their name, unconscious biases infect organisations and often go completely undetected. HRM examines three that HR should be on the lookout for.

This year, HRM looked at three diversity and inclusion matters that don’t always receive the attention they deserve in the workplace. Obvious biases like gender or racial discrimination have a tendency to dominate the conversation and, while these issues are extremely important, there are other biases that lurk beneath the surface. They’re just as devastating and much easier to miss.

In this article, we’ll revisit the issues of compassionate bias, classism and size bias to ensure we head into the new year with a goal to create psychologically-safe work environments for everyone.

1. Compassionate bias

Unlike some of the other ‘isms’ – such as racism or sexism – some people don’t take ageism very seriously. Some don’t consider it to be an issue at all.

Ageism can touch people of all ages. Candidates appointed to leadership positions at a young age might face condescending attitudes from those older than them, for example. Also, if someone works in a specific industry – say, technology or entertainment – the clutches of ageism can hit them much sooner than most would anticipate (in their 30s or 40s).

But as HRM has covered before, it’s usually older employees who bear the brunt of ageism.

For many older employees, ageism doesn’t take the form of hate or harassment, instead they are often treated with pity or viewed as incompetent; people think they’re unable to keep up with rapidly changing technology. Here, employers and colleagues fall into the category of ‘compassionate bias’ or “the bias that makes us feel warm and fuzzy”.

Compassionate bias isn’t just reserved for older employees, people living with disability can experience it too. When HRM spoke with Susan Fiske, Eugene Higgins professor of psychology and public affairs at Princeton University earlier this year, she said both groups “were well liked, but evoked pity”.

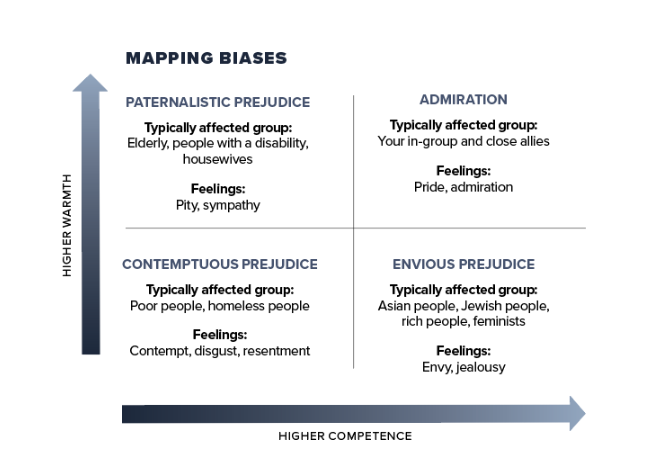

Older people and people with a disability, she said, rate highly for warmth and low for perceptions of competence (see graph below). The prejudice typically felt towards them is therefore paternalistic, Fiske added.

To help employees identify compassionate bias, experts recommend the Harvard Implicit Association Test. This measures a person’s strength of association between concepts and certain groups of people. For example, the people’s association between clumsiness and people living with disability. Its purpose is to raise awareness, show people the extent of their biases and help them eliminate this discriminatory behaviour.

Beyond this, assistant professor of management and organisations at NYU Stern School of Business Dr Michael North suggests four specific measures workplaces can take to address compassionate bias, in relation to ageism, in the workplace. They include:

- Implement flexible, half-retirement options – this could look like an employee working part-time while drawing from their superannuation to supplement their income.

- Prioritise older worker skills in hiring and promotions – consider where an older employee’s skills could fit into your workplace. For example, research shows they have higher levels of respect, maturity and networking abilities.

- Create new positions, or adapt current ones, to accommodate older employees – train employees to fill positions that best capitalise on their current skill set.

- Change workplace ergonomics – not all older workers are feeble, but those who do have physical limitations should feel that their workplace is willing to accommodate them. What this looks like would be specific to each individual.

2. Classism

Earlier this year, the Diversity Council Australia (DCA) released a damning report revealing that more than 40 per cent of employees from lower classes experienced discrimination and harassment in the workplace.

The DCA’s Class at Work report found 17 per cent of lower class respondents felt ignored at work, and 22 per cent felt they missed out on opportunities or privileges. Worst of all, these employees reported feeling excluded by their colleagues, with 20 per cent of respondents saying they were left out of social gatherings.

Earlier this year, DCA CEO Lisa Annese told HRM that not enough workplaces considered class an important intersectionality that would affect their workers. In some cases, she says, it actually has a bigger impact than other demographics.

“Our research looked at nine diversity demographics… but class was the diversity demographic most linked to workplace inclusion – there were clear differences between self-identified lower and higher class people on every question we asked,” says Annese.

As HRM also reported, class became even more of an issue in 2020, with a report showing that over four million Australians are limited to mobile-only data, meaning working from home is no piece of cake. With a nation-wide move towards remote work on the table, this could potentially lead to lower-class candidates missing out on or choosing not to apply for roles that require staff to work from their homes.

Annese believes change on class issues should come from the top with leaders beginning by acknowledging their own privileges.

“We know leaders are more likely to have come from certain backgrounds. Not all of them but many. And they should understand how that might impact their organisation and possibly add to unconscious biases,” she says.

The Class at Work report included nine recommendations for D&I practices, but HRM has pulled out the six that can be implemented sooner rather than later:

- Make class a standard part of D&I vocabulary and practice.

- Keep all intersections in mind (i.e. when developing a gender diversity initiative, don’t forget to consider the experiences of women from culturally diverse backgrounds).

- Ensure that D&I initiatives reach and positively impact people from all classes.

- Recruit for class diversity.

- Use inclusive language in your job ads and internal communications.

- Review informal networking and its impact on your workplace.

3. Size bias

Like the other biases in this article, some people wouldn’t think someone’s size as a potential point for workplace discrimination. And we’re not talking about overt body shaming – that would be classified as workplace bullying. Size bias is a much more subtle yet equally pervasive issue.

Learn how to effectively manage cases of workplace bullying and harassment with AHRI’s half-day course – next running on 16th February, 2021.

A 2012 Harris Interactive/HealthDay poll found 61 per cent of people don’t consider making negative remarks about someone’s weight to be offensive. Instead, they see it as showing care by worrying about the health of the overweight person.

Larger employees face a raft of issues in the workplace. Some are the victims of outright bullying – like the employee whose colleague watched them take a bite of a doughnut and commented they were “slowly killing” themselves, as HRM reported earlier this year.

For others, the harassment was more subtle, like the woman who was the only employee to receive a gym membership as her ‘end of year bonus’ (all her colleagues received financial benefits).

People who experience size bias often feel shamed into silence, which is why Annese suggests employers implement bystander training in their workplaces.

“The person experiencing the discrimination might be mortified or might not want to be seen as being difficult. It really helps if somebody else speaks out. We need allies in our workplaces,” Annese told HRM earlier this year.

Bystander training aims to empower employees to speak up whenever they witness problematic behaviour – be it discrimination, bullying or harassment. Bystanders don’t have to actively engage the perpetrator (which in the most severe cases could be dangerous). Instead, they can take certain actions such as interrupting the situation by calling the victim into a “meeting”.

The bystander can also use this opportunity to check on the victim and let them know they are willing to support them should they want to make a formal complaint.

Those who experience size bias can feel isolated and judged by their peers, so letting them know you support them is a very important part of making them feel like a valued member of your workplace.

Biases are a natural part of being human and are mostly involuntary, but Annese recommends learning to challenge your own unconscious bias whenever possible. She also notes that reprogramming yourself to overcome these biases can take time but says it’s worth it.

Unconscious biases can be particularly difficult to process because a lot of the people who perpetrate them think they’re being kind. But if this year has taught us anything, it’s that life is hard enough. Let’s try to make work psychologically safe for everyone, it’s really the least we can do.

Great article – well written, and food for thought. Thank you.

Talk about putting people in “boxes” – is this a bias There has been quantitative means of defining position competence and sizing position before we even consider the applicant. Then the same quantitative system takes over in the matching (of competence and attributes) process I.e. recruitment, assessment etc. While these systems will never take out all the bias but goes a long way to how we manage other assets. These systems were developed in early 1990’s and helped pull us out of that recession, improved the diversity etc. However as soon as the economy recovered and boomed we seemed to… Read more »

Size bias is not restricted to weight. There are sizes you have no control of, such as, “You really are tall aren’t you? “ Like to set out to get this tall. “You mean your feet are that big?” Like I pulled at my toes every night to make this happen! “You mean you wear that size hat?” Yer right, it’s to keep my large brain in. I have “suffered” from all three of those. What the bloody hell do they think I can do about them?