Automating roles in your organisation is sometimes a necessary decision. But you don’t have to alienate staff, or even fire them, when doing it.

A lot of people are scared automation will make their job redundant. One study even found evidence that fear of automation is causing workers enough anxiety to make them physically ill.

Research from McKinsey looked forward to 2030 and found that while less than five per cent of occupations are fully automatable (predominantly those with a lot of repetitive physical activities, or data processing or entry) 60 per cent of jobs can have 30 per cent of their activities automated.

While this suggests a future where very few of us won’t be affected by automation and just a small number should be truly ‘scared’, it needs to be unpacked.

Organisations treat different roles differently. In some organisations that 30 per cent of activities might be the most valuable contribution you make. Optimistically, removing almost a third of your activities would free you up for other tasks. In reality many companies will simply make a third of the people in your role redundant.

How HR manages staff in this situation will become an evermore important skill. Because while redundancies are never easy, imagine how much more difficult it must be when the staff who are leaving know they won’t find another role elsewhere.

If done right, redundancies can run so smoothly that the staff leaving actually appreciate the company for how they handled it, and even help with the transition. If done incorrectly, redundancies can hurt the engagement of the remaining workforce. This might be especially true of those who actually conduct the automation.

It’s not just those being automated

A less told side of the automation narrative is the distress felt by those who are tasked with automating the jobs of their colleagues.

This experience is captured in an article from MIT Technology Review titled ‘Confessions of an accidental job destroyer’. It’s the intimate tale of a woman streamlining a company’s mould making process with 3D printing during a summer internship. She quickly discovers that to complete her task a man she calls ‘Gary’ is crucial, as he has over 30 years’ experience in making moulds. She also discovers that when she’s finished Gary will be redundant.

Gary goes along even after she makes him aware of this, though he does complain about the company. After she’s done Gary is moved to another job, but he doesn’t like it (or the company itself anymore) and so he quits.

An article on Gizmodo refers to more employees who have to automate their colleagues’ jobs, and their responses to the situation. Some understand the stakes immediately, others only realise the full implications of what they’re doing later on. One even quits when he realises.

So, given the potential harms, what’s the right way to automate staff out of a job?

Be upfront

In the article on MIT, the writer says they reconnected with Gary. He was happy to talk to her. He says the company took “a very aggressive stance with [him] and some other employees in similar positions… I assumed, wrongly, that I would have an opportunity to follow along with the evolution of the process.

“The ‘official position’ of the company was that there was no attempt to change anything about how things were being done.”

If that’s true, it’s no wonder Gary didn’t stick around. The company lost a long-time worker and made the person who helped them with automation feel so nervous she felt compelled to write about it years later.

The lesson is obvious, if staff are going to have their jobs either partially or fully automated there is no benefit to pretending otherwise. In fact, you give them their best chance to help themselves, and your organisation to succeed, if you tell them immediately. They can have the opportunity to think about retraining, you can plan more openly for the automated future, and you can retain the right staff if the automation process goes awry.

Get them to self-identify

The most intriguing option for an organisation that knows automation is in their future is to follow the example of UK insurance company Aviva. In 2017 it asked 16,000 employees if their job could be automated and offered to train them for alternative jobs if they said ‘yes’. Doing this has multiple benefits.

- It establishes your organisation’s openness.

- It makes the conversation around automation less toxic, and staff feel less afraid.

- It gives your company valuable data to help direct automation funding and fine-tune a workforce strategy.

- It’s a positive story that plays well to current staff and potential job seekers.

Retrain or reposition them

Everyone in the future will need technology-based skills, but not everybody today has them. At the 2018 ReimagineHR conference in Sydney, a presentation from Gartner looked at the digitalisation of organisations. It quoted the head of talent management at an insurance company saying, “Just because we don’t have the right skills, doesn’t mean we don’t have the right people.”

This is an important point because hiring is quite costly, and for some roles it’s very difficult. As HRM wrote in late 2017, the workforce who can handle AI related roles is very small (Canada has a similar population, but double our talent pool).

If you want someone who has expertise in a specific role with strong technology skills, it might end up being a smaller investment trying to retrain rather than firing and hiring someone else. After all, a world economic forum report found that 51 per cent of Australian workers will need upskilling or retraining before 2022. This will create a shorter supply in the talent market.

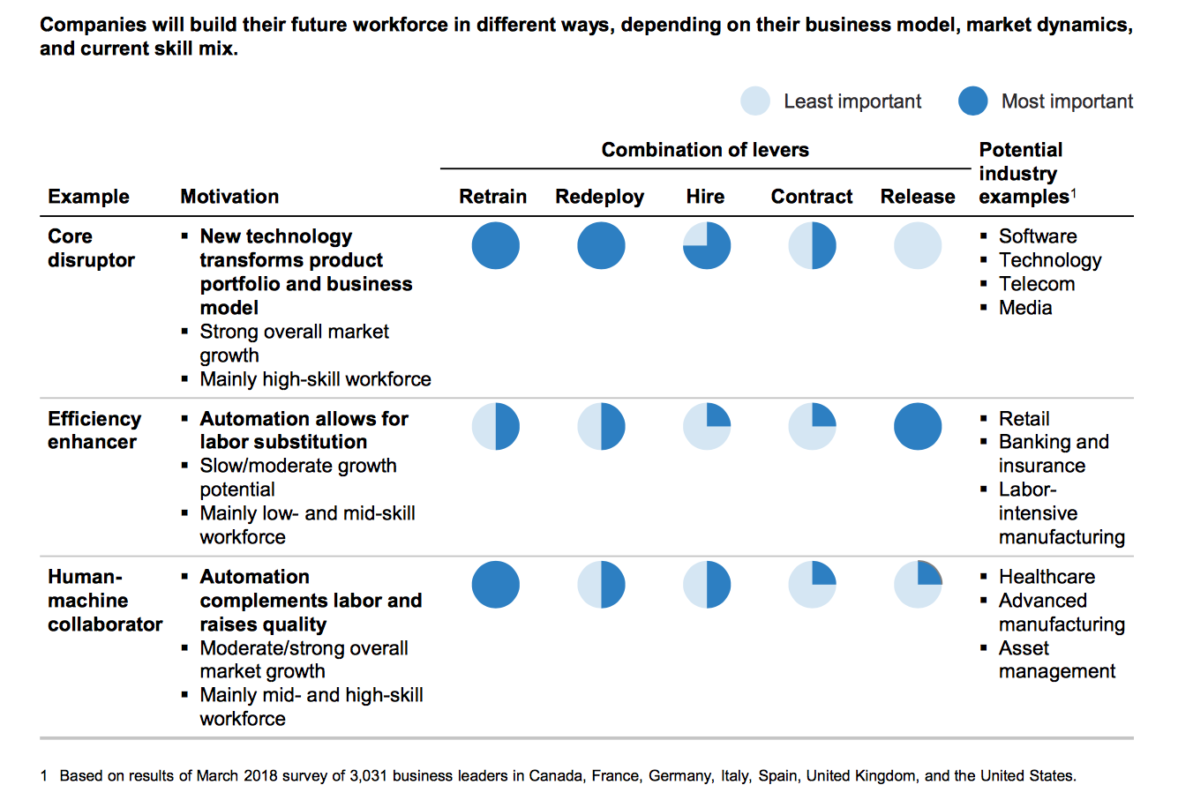

A different piece of research by McKinsey looked into the five strategies employers can take when faced with automation of job tasks; retrain, redeploy, hire, contract and release. Not surprisingly, the importance of strategies is decided by the disruption each industry faces.

Retraining and redeployment were rated as relatively important to every industry. Of a release strategy, the report says, “the risk is that knowledge of the company, culture, and operations is lost. Layoffs can also diminish employee productivity and satisfaction, and can be difficult and costly to carry out.”

Still, redundancies are sometimes a business imperative. But there is a right way to do it, and that’s being upfront.

Recent surveys have shown that those projects that use formal change management processes have a much higher return on investment than projects that do not. Sign up for AHRI’s ‘change management’ short course to get ahead on your next strategy.