A look at the evidence, and whether Australia’s particular situation means we are exempt.

Though Australia has had a relatively lucky experience with the COVID-19 pandemic, people are still worried about getting infected as the lockdown restrictions ease. Workplaces all over the country are doing what they can to standardise cleaning, social-distancing and personal hygiene (though employees seem to think these efforts aren’t sufficient).

One notable absence from these return-to-the-workplace conversations is whether people should be wearing masks. This article will look at why that is, and whether the research suggests it should change.

Culture is powerful

On one level, it’s not surprising Australia is not seriously considering wearing masks. It’s just not a cultural norm here (or in any Western country for that matter).

On another level, it is a little surprising it’s not being considered more seriously. Afterall, rigorous hand washing and social distancing also weren’t cultural norms, yet they have been adopted very quickly.

One of the significant differences between these things is how they were talked about early on. The best opportunity to normalise mask wearing would have been in February and March, when people were desperate to learn how to protect themselves and their families. But instead of being told that masks could be effective, we were often told by both the media and public health officials (both local and international) that they were unnecessary (and perhaps dangerous) unless you were a health professional or had symptoms.

It turns out the reason for this messaging may have been to prevent a shortage in health care that could have been disastrous. But having been told they weren’t effective at all, it has made it difficult to convince people to wear masks even now that the danger of a shortage has passed. Our cognitive tendency towards anchoring means that we tend to privilege initial information over more recent information, regardless of context.

This is an issue, because the research suggests that a lot of indoor workplaces could become hot spots for viral transmission.

COVID-19 and the indoors

To be blunt, indoor work situations can be quite dangerous during the pandemic.

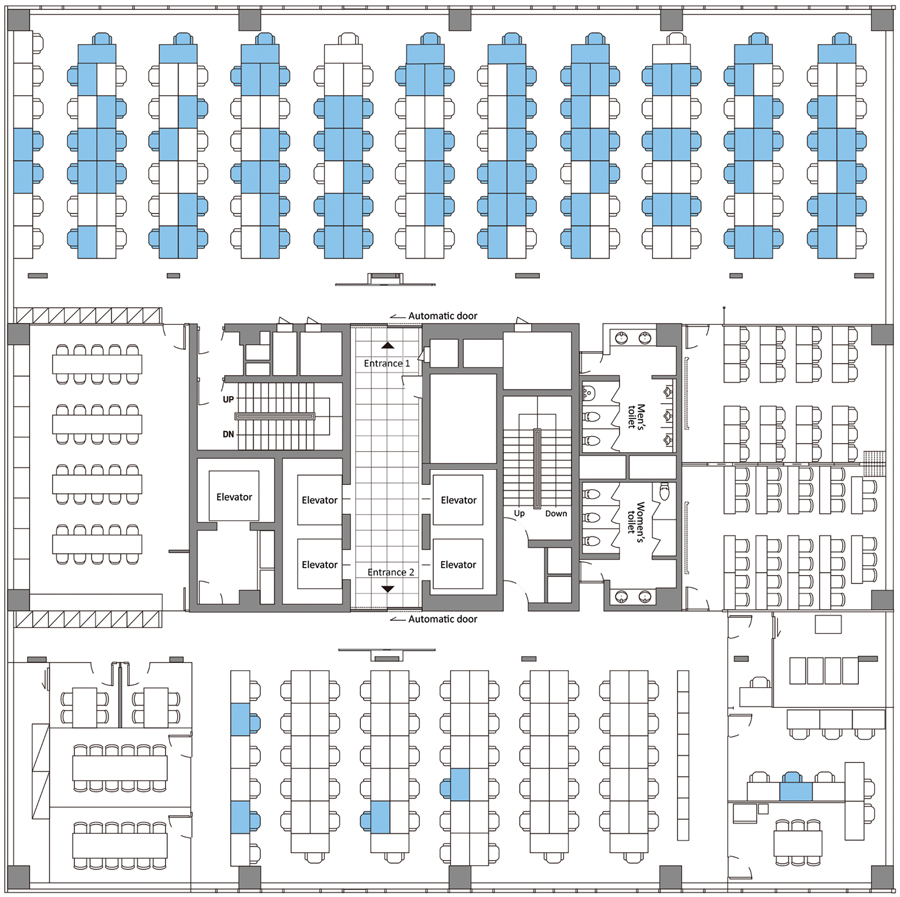

In a study that looked at transmission in a South Korean 19-storey building, a total of 1,143 people were tested for COVID-19. Ninety-seven tested positive. Of those, 94 worked in the same 11th-floor call centre. This business had 216 employees all up, so this translates into an attack rate of 43.5 per cent. Driving home the risk of longer-term proximity with colleagues is a diagram of where the employees sat in the office (positive infections in blue).

Source: CDC

Source: CDC

These workers shared the same bathrooms and elevators. So it wasn’t incidental contact with colleagues that spread the virus, but rather a longer period of working near them.

Other studies back up the danger of indoors. One from Japan found that “the odds that a primary case transmitted COVID-19 in a closed environment was 18.7 times greater compared to an open-air environment”.

Of course, not all indoors situations are equal. The closer you work with others, and the more you shout or sing, are all factors that have been linked with increased chance of infection – meatpacking plants are the most famous example.

But even if indoors is bad, does wearing a mask help?

The evidence for mask wearing

The research proving the effectiveness of masks – even homemade ones – is growing. A Cambridge study, written about by Reuters, found having 50 per cent of the population routinely wear masks reduced the factor of viral spread of COVID-19 to less than one person per infection (so curbing exponential growth).

“Our analyses support the immediate and universal adoption of face masks by the public,” Richard Stutt, who co-led the study, told Reuters.

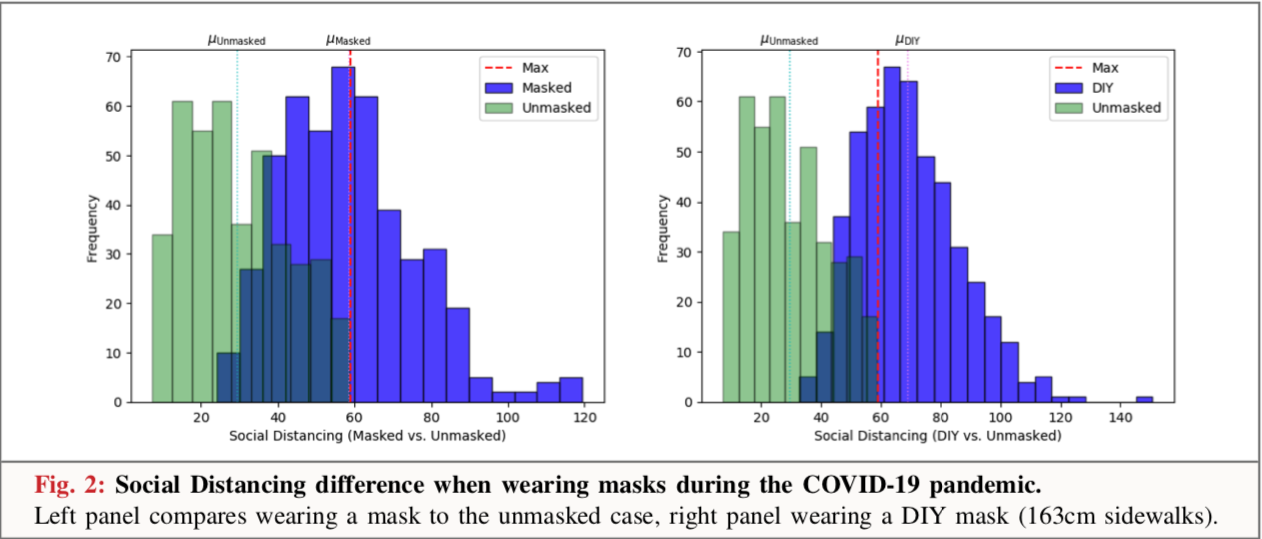

Far from giving mask wearers an undue sense of vulnerability (a much cited reason for not promoting their use), the research shows that masks encourage more social distancing. An Italian study found that the absence of masks meant people were more likely to stand closer to each other. The authors believe it has to do with ingrained social conditioning. If no one is wearing a mask we just feel safer, even if consciously we know we’re not. The mere visual stimulus of a mask is enough to jolt us into safer behaviour.

Source: University of Padua and the European Institute for Science, Media and Democracy

Source: University of Padua and the European Institute for Science, Media and Democracy

The safety of mask wearing certainly extends to workplaces. One powerful example: two hair stylists in Missouri who tested positive for COVID-19 did not spread the infection to over 140 clients. Both the stylists and their customers wore masks.

But isn’t Australia safe regardless?

Given the success Australia has had in suppressing the virus you could make an argument that asking employees to wear masks is superfluous. Afterall, it’s not as if masks are 100 per cent effective, and no one can catch the virus if it never enters the workplace in the first place.

It would be way outside the purview of this article to actually recommend mask wearing – this is very much a decision every organisation should assess for themselves. What can be said is that, given the growing evidence for its effectiveness, discouraging the use of masks in your workplace just because it looks weird and isn’t culturally normalised might be something you regret down the line.

An interesting read. Personally speaking, if I felt we here in Australia were more at risk and therefore be more likely to benefit from wearing a mask, I would be all for it. Given our success in controlling Covid-19 in this country WITHOUT the need to don masks means I would not think it necessary at this stage

Thank you for the information Girard. As a CPHR + microbiologist, I must say the article is well written; exceptionally high standard.

I both do, and don’t agree with this article…. this is another case of ‘be careful not to twist data to fit the result that you want to achieve’… this is the greatest mistake that many people make with data, and is the quickest way to get people to not take you seriously. The point I would make in regards to your reference data, is that you are looking at a scenario where people worked in close contact, and your diagram clearly shows the lack of social distancing of these staff. Masks or no masks, it is not surprising to… Read more »