In part two of HRM’s long-term impacts of COVID-19 series, we look into how remote work is having some alarming impacts on our cognitive functioning.

Shortly after remote work arrived on the scene, it was praised as an effective way of replenishing our mental and physical resources.

With fewer distractions from colleagues in a busy workplace, we could put our heads down and work in a quieter, often more peaceful, environment.

We quickly revelled in the ability to plonk ourselves in front of a computer two minutes after rolling out of bed, allowing us to cut out a stressful commute time and achieve better work-life balance.

But a few months into the great WFH experiment, most of us cottoned onto the fact that remote working isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

With no commute time to separate work from home life, it’s often harder to switch off from the responsibilities of a demanding job, and we quickly realised that distractions in the workplace are replaced by interruptions at home, whether that’s kids or housemates or the temptation to finish domestic chores.

And these are just some of the more immediate challenges we face when WFH. Remote work is having a significant impact in other ways that are far less readily apparent. HRM speaks to Natalia Ramsden, founder of London-based brain optimisation clinic SOFOS Associates, to explore the cognitive impacts of remote work, and what prolonged periods of working from home could be doing to our brains.

Don’t have time to read the whole article? Here are the key points:

- The number of decisions we have to make in a work context has increased significantly since the introduction of remote work. As a result, we have a greater cognitive load to manage. Cognitive load also increases in situations of uncertainty.

- To deal with the cognitive impacts of remote work, Ramsden encourages employees to take regular breaks, and consider their health and wellbeing practices such as sleep hygiene, nutrition, exercise and stress management.

- Remote work can reduce the opportunities for learning, since a home environment typically isn’t as rich and stimulating an environment as the workplace. It’s possible to create a more dynamic working space at home by mixing up your routine.

Increased cognitive load

Even before COVID-19, the demands of modern life along with rapid technological advances increased our cognitive load – defined as the total mental effort used in working memory to process information and make decisions.

“People are living complex, multi-faceted lives, perhaps in a way they did not many years ago… Executives may hold a number of board positions, contribute to charitable organisations, have a family and be involved in various associated activities – lives seem quite full to say the least,” says Ramsden.

“In addition to that, our way of living has changed – we now have so much content for our brains to wade through.”

Throw remote work into the mix, and the cognitive demands quickly multiplied. It’s relatively straightforward to show up to a meeting in person, but virtual meetings by comparison require consideration of many different elements. Checking that every participant can access the meeting, working through technical glitches and ensuring your backdrop is in a presentable state can be mentally taxing.

Experts also suggest our brains are working overtime to try and comprehend seeing more than one person on a screen as we’re unable to make meaningful eye contact with anyone as we would in person. We also tend to be distracted by seeing our own faces, so we’re not always giving others 100 per cent of our attention. (You can read more about this in HRM’s breakdown of video call fatigue).

Bout of doubt

Ramsden says greater attention is needed if we’re attending to various different stimuli simultaneously in an unknown environment as cognitive load is likely to spike in situations of uncertainty.

“Working memory is heavily involved in problem solving, decision making and processing information, and its capacity is limited. The more novel a problem or situation you are facing, the more you call on your working memory to help,” says Ramsden.

“It isn’t until an individual is an expert that this ‘information’ is transferred to long-term memory. Very simplistically, you may find you require more effort when dealing with uncertainty because of the call on working memory rather than long-term memory.”

It therefore seems plausible that as we acclimatise to the new world of work, our cognitive load will decrease as these additional decisions become a more entrenched part of our daily routine. (See HRM’s article on change fatigue for more information).

But Ramsden is less optimistic that we’ll automatically adjust to the new state of affairs over time.

“I am not sure that the increasing cognitive load people face is necessarily purely related to the pandemic and working from home set up. I suspect that we have been on this trajectory for quite some time because of things like technological advancements, ways of living, and expanding age span,” says Ramsden.

“The work from home life [some of us have] been living this past year has contributed but it might be that increasing demands on our bodies and brains is a result of modern life (and the things we no longer do like down time, switching off etc) than COVID-19.”

Detrimental cognitive impacts of remote work

Even if there are more decisions to consciously work through, apart from being a little more tired and overwhelmed than usual, why is this such great cause for concern?

Burnout is one good reason. We might be used to thinking of burnout in a psychological sense, says Ramden, but it can also have dire physical impacts.

“Reports have shown the physical consequences on the brain as a result of burnout – studies have shown that the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex (all linked with stress response) age prematurely when an individual experiences burnout. The human body is a complex set of symptoms so any long-term impacts will not be ring fenced in the brain.”

Got an HR question that needs a personalised response?

AHRI members can send their questions to AHRI:ASSIST.

Ramsden highlights how a heightened chronic stress response can lead to sleep disturbances, consequently impacting heart health. It can also cause levels of cortisol to spike, which can have short- and long-term consequences including diabetes, anxiety and depression.

Preserving cognitive energy

We need to both increase cognitive capacity, and reduce cognitive waste to stave off burnout and help individuals who “want their brains to do more, to work faster, and more efficiently”, says Ramsden.

Taking stock of health and wellbeing practices to ensure good sleep hygiene, nutrition, exercise and stress management is a great starting point.

Implementing these strategies and effectively managing a WFH routine with less face-to-face interaction from colleagues necessitates managerial support. Supervisors can help to ensure effective boundaries between home and work life are maintained, so that employees are clear on their role responsibilities, and don’t feel they are expected to be available during non-work hours.

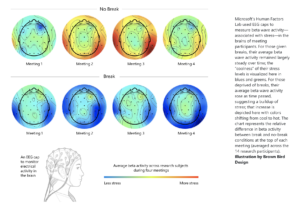

Carving out regular breaks is another strategy worth putting in place. New research from Microsoft has reiterated the importance of breaks, by indicating how they can help to combat stress caused by back-to-back virtual meetings (see graph below).

Ramsden says this recent research is a “call out on the importance of breaks rather than how we go from meeting to meeting irrespective of medium”.

“The message here should be to create a work structure that leverages our cognitive capacity irrespective of where and how that work is taking place.”

Image: Microsoft study, 2021. Illustration by Brown Bird Design

Learning losses caused by cognitive impacts of remote work

In a physical workplace, we’re constantly thrown a variety of different stimuli. It can feel overwhelming at times, but the opportunities for group problem-solving, formal and more spontaneous conversations, and creative collaboration present valuable learning experiences.

Remote working doesn’t offer the same input, and it can leave employees devoid of a dynamic and stimulating environment.

“When we talk about a rich environment, we mean one that offers the brain both physical and social stimulation,” says Ramsden. “Stimulating environments are better for mental health and cognition because they encourage the growth and function of neurons – brains exposed to these environments have higher rates of synaptogenesis (the formation of synapses which connects neurons in the nervous system. Imagine this as how messages are transferred or communicated). Very simply speaking, this process leads to increased brain activity.”

Ramsden caveats this observation by noting that it’s not impossible for a home working setup to foster a dynamic learning environment – it just requires some creative thinking.

“Perhaps one of the most limiting aspects of working from home or virtually is the monotony. For most people, each day working from home is incredibly similar to the one before. They follow the same routine, sit in the same place, stare at the same screen and whilst in some ways this seems productive, they aren’t exposed to a changing, unpredictable environment.”

“We now have so much content for our brains to wade through.” – Natalia Ramsden, founder of SOFOS Associates.

To break up the monotony and minimise the negative cognitive impacts of remote work, Ramsden recommends organisations encourage their remote employees to alter their daily routines.

Studies conducted by Simone Ritter from the Department of Social and Cultural Psychology at the Radboud University Nijmegen about increasing creativity, for instance, achieved “great results by doing the simplest of things, changing the order of doing things in everyday life – i.e, making your coffee a different way”.

“Expose yourself to something different every day,” she says.

It’s great advice for any day of the week – and particularly so for monotonous WFH days that might need a little more variation.

Read part one of this limited series, on the long-term impacts COVID-19 will have on our connections at work, here.