Those who entered the workforce in the last ten years are faring worse than their predecessors, says a new report from the Productivity Commission.

While Australia’s workforce grapples with the immediate impact of the pandemic, new research shows its long-term impact could be borne most heavily by Australia’s youngest workers.

A new report released by the Productivity Commission (PC) last week looked at the lingering impacts of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis in Australia and found they disproportionately affected those under 35.

Their salaries and job opportunities over the last decade have been less desirable than those over the age of 35, and worse than employees in the same age bracket prior to 2008.

The researchers refer to this long-term impact on careers as the “scarring” from the GFC and warn that COVID-19 has reopened a lot of those old wounds.

A decade-long issue

The report provides some answers to long-standing questions about Australian wage stagnation.

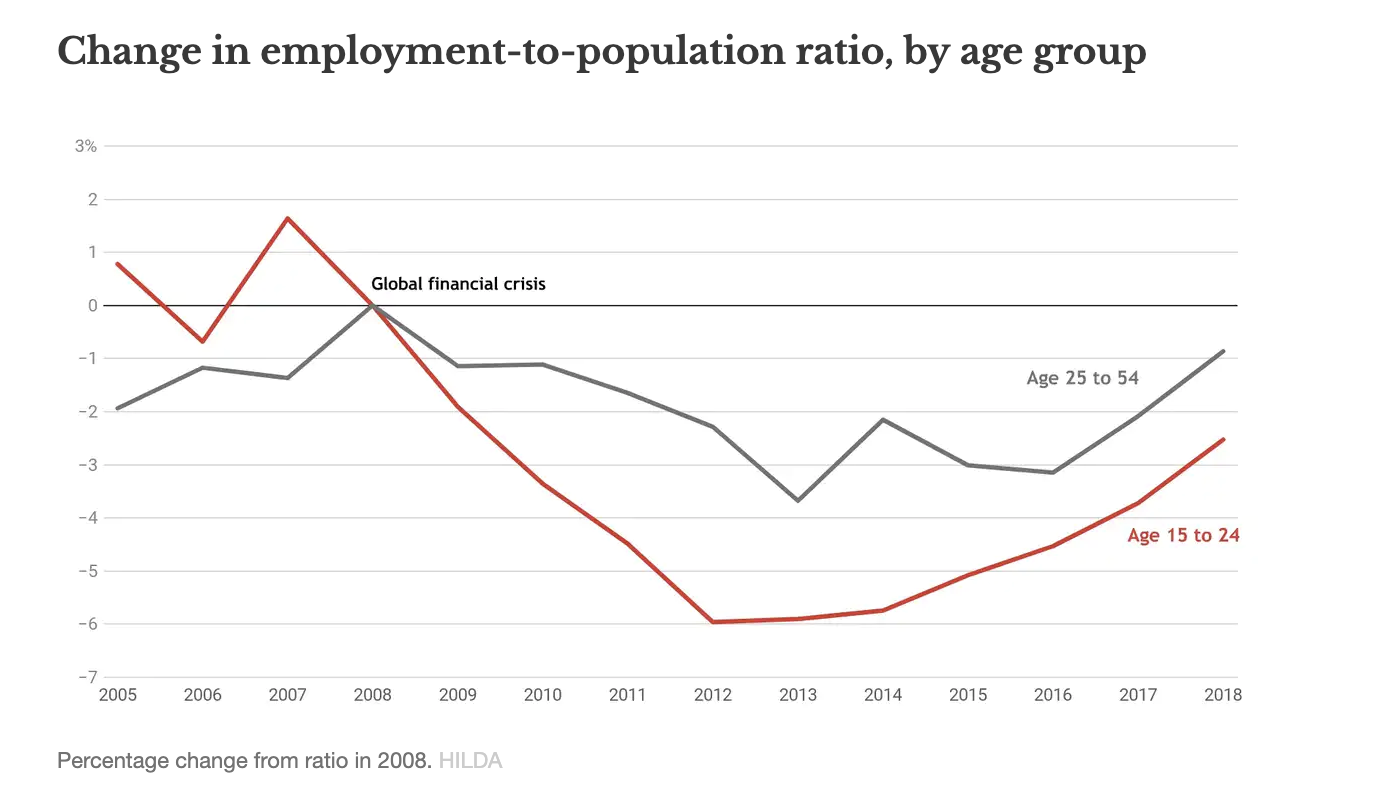

The graph below draws on data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Australia (HILDA) survey to show that while younger workers were doing better than older workers prior to the 2008 market crash, following it they were in a significantly worse position and it took them far longer to start climbing back up. Chances are we’ll see a similar trend in the wake of COVID-19.

“It turns out that the ‘low wage growth’ story is essentially a story about people under 35,” says PC commissioner Catherine de Fontenay. But why is this the case?

Many young workers mightn’t even be aware their incomes are part of the collateral damage of the GFC, because the current job market is all they’ve ever known. But the weak labour market that came off the back of the GFC coincided with the slowing of Australia’s mining boom, meaning the country had an oversupply of qualified job seekers.

Although jobs were available – Australia’s unemployment rate post-GFC only rose by 1.5 per cent compared with 4.5 per cent in the US – there just weren’t enough jobs that aligned with graduates’ skills and qualifications.

Of the jobs that were available, many of them weren’t full-time. They also tended to be lower-skilled, lower-paying jobs. This increase in part-time work disadvantaged younger workers in particular.

“Full-time employment has been in long-term decline since the 1980s for people aged 20-24, coinciding with them spending more time in education,” the report reads.

“That decline paused briefly during the boom (from 2001 to 2008). That said, the decline in full-time employment after 2008 occurred primarily for people aged 15-24 who were not studying, which suggests that it was driven by a weak labour market rather than by a preference for more education.”

Low-scoring jobs

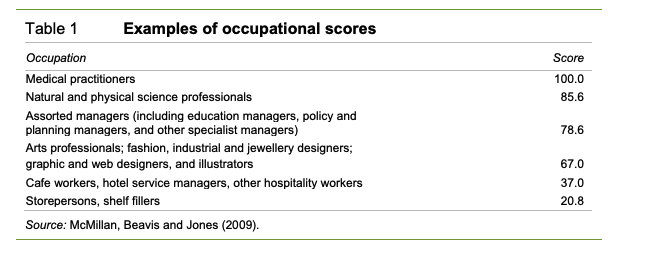

Using the Australian Socioeconomic Index – an occupational status scale that measures jobs based on their educational requirements and average earnings – the researchers drew on data from the HILDA survey and found that in the two decades preceding the the GFC, occupational scores were relatively high.

However, between 2010 and 2015, there was a decline in the percentage of employees under 35 gaining high-scored occupation opportunities – this was particularly the case for those in the 20-24 age bracket.

During this same timeframe, employees aged 35-54 saw an increase in high-scored occupations, which suggests younger workers’ job prospects are more sensitive to poor job market conditions than their older counterparts.

Also, low-scored jobs are inextricably linked with lower wages – the report backs this up.

Employees between the ages of 20-34 experienced very little wage growth from 2008-2018. The report suggests this is due to lower starting wages, less bargaining power and many people working for smaller organisations, which tend to offer lower compensation.

Not only did wage growth for the 20-34 age cohort never fully recover, it actually went backwards.

Prior to the GFC, growth in wage rates averaged 1.46 per cent per year. Following the economic crash in 2008, it dropped to just 0.86 until 2012 – then it declined by 0.08 each year. Compare this with those in the 35-64 age range. Before the GFC, wage growth rates averaged 1.7 per cent per annum, dropped to 1.36 from 2008-2012, then 0.62 per cent afterwards.

More education, more competition

While the increase in university graduates has been a boon for the industries desperate for highly skilled workers, it’s also what’s causing many young employees to start off on the back foot.

Job seekers with a bachelor’s degree were worse off in 2018 than in 2001, the PC report found. In an article for The Conversation, de Fontenay says this could be due to the increase in university and vocational education following the GFC; qualified candidates outweighed high-level job opportunities.

“Law graduates increasingly found themselves working as paralegals or in cafés,” she says.

The competition for jobs at the top of the ladder (high-scoring occupations), resulted in more competition at the bottom too.

“When we turn to people with sub-bachelor qualifications [vocational training], the probability of obtaining a high-scored occupation declined for all [age] groups,” says the report. “And for young people aged 20-24, the decline in average occupational score was substantial.”

Those graduating university between 2013-2015 had a particularly tough time, with the report indicating these graduates were only able to secure jobs towards the lower end of the occupational status scale and were likely to remain on this low job trajectory.

“It suggests that poor initial jobs for graduates have serious long-term consequences,” says de Fontenay.

This wasn’t just the case for the 2013-2015 cohort. Once a young employee was locked into a role in a lower-scored occupation, the researchers found they were likely to stay there if they joined the workforce during unstable economic times. That’s not good news for the graduate cohort of 2020 and beyond.

The PC’s report predicted that young workers would have likely soon recovered from this decade-long dip in job opportunities and wage growth, but COVID-19 has dashed that hope for the foreseeable future.

While many job seekers might be using this time to upskill for when the job market recovers, the research – and history – suggests this won’t help much. Our post-pandemic world could end up looking very much like it did in 2008 – too many qualified graduates and not enough full-time jobs.

Now more than ever employers need to think about how they’re engaging their workforce. AHRI’s short, virtual course job analysis and job design will give participants the skills to be agile and adaptive in how you make the most of your workforce.