Experts and a person born with a facial difference explain the challenges of gaining meaningful employment and promotion opportunities while living with a disability.

How can you get your foot in the door if your wheelchair doesn’t fit through it? You can never truly understand the specific difficulties many employees and job seekers face unless you talk to someone who lives with a disability.

Carly Findlay identifies as a disabled woman with a facial difference. Born with ichthyosis, a rare and painful genetic skin disorder, she has been an active voice in the disability community for some time now. It’s likely you’ve already heard of her or read her work.

Findlay holds a masters of communication from RMIT University and a bachelor of e-commerce from La Trobe University, so when I was speaking with her over the phone, I was shocked by the fact she’s been asked to work for free. She’s much more experienced than I am. She’s received higher qualifications, written for larger media platforms and has even penned her own book. Despite this, no-one has ever asked me to work for free. Yet people have asked Findlay to do just that. And not because she just loves volunteering her time and writing expertise, but because she looks different.

“Many people with a disability rely on charity,” says Findlay. This means that many organisations that have “done their bit” put people with a disability in a different category and expect their work to be unpaid.

“They see disabled people as charitable objects,” she says. “We really have to value ourselves. If we continue to say yes to working for free, there will be an expectation that every disabled person should work for free.”

Now, as the access and inclusion officer for the Melbourne Fringe Festival, Findlay enjoys an inclusive work environment that’s flexible and supportive of her needs – but that hasn’t always been the case.

Professional barriers

As well as the obvious physical barriers, such as a lack of wheelchair access preventing someone from using the bathroom or entering the building, Findlay highlights attitudinal barriers such as the low expectations that are sometimes placed on people with a disability.

“I work really hard to raise people’s expectations. I used to feel that I had to impress someone before they’d even met me. I don’t care as much anymore,” she says.

Once disabled people have overcome the initial, and perhaps biggest, hurdle of gaining employment, promotion opportunities can be few and far between. During a 15-year career in the state government, in a series of executive assistant and event planning roles, Findlay “didn’t really progress at all”.

“At the time, I was forging my freelance career in the media, and when I’d go for communications jobs in the government, they’d tell me that I didn’t have enough experience and didn’t write for a big enough audience. I’d say to them, ‘A story I wrote was number one on The Age today, so I’m not sure what you mean by that,’” she says.

When you’re in the workforce as a disabled person, not only do you have to fight against the misconceptions of your colleagues, but you also have to manage your responses to their behaviour.

“When I’m on the street and someone stares or is rude to me, I can react any way I want. I’m generally polite, but sometimes I’m not. It depends if it’s deserved or not. But in the workplace, it’s really tricky because you could be up for harassment even though you’re only reacting to something more inappropriate. That’s something I find really hard.”

False expectations

Findlay’s experiences, unfortunately, are not unique. The bright side is that there are many organisations set up to assist employers to create a disability-fit workplace. Daniel Valiente Riedl is the general manager of Job Access, a government-led organisation gathering momentum around disability employment and supporting disabled workers across Australia.

“We think about disabilities in terms of not what the person can’t do, but how we can adapt their environment so they can do anything they wish to do,” he says.

As an example of an employer assuming it understood her limitations, Findlay recalls going for a job in the health care sector. They told her they didn’t think she was right for the role because the job involved doctors who “would be more interested in [her] skin condition” than in the product she was meant to be selling.

Employers shouldn’t assume they know what a disabled employee can and can’t do. Instead, they should take Valiente Riedl’s advice above and alter their environment to assist the disabled worker. Perhaps that’s an electric wheelchair for a paraplegic doctor so they can whizz around the emergency department with ease; perhaps it’s offering Auslan training to your team to help them better communicate with a deaf colleague.

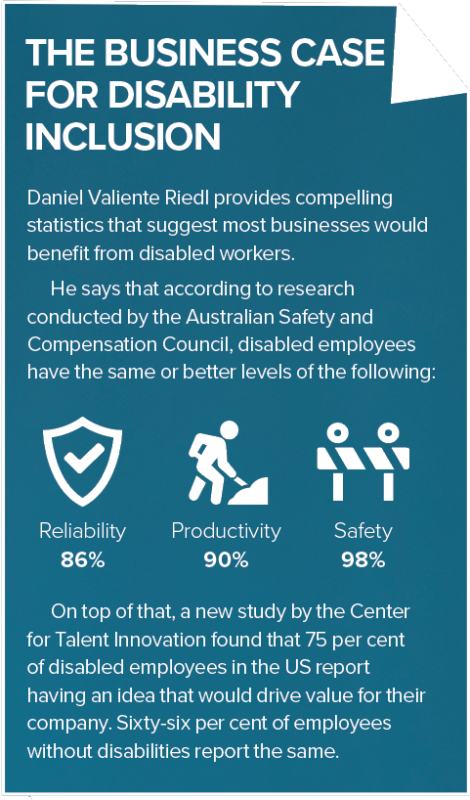

“It’s vital to understand the barriers that are holding employers back from hiring people with a disability. The Department of Social Services says 77 per cent of employers believe it’s important for their workplaces to include people with disabilities, but only around 35 per cent demonstrated any behaviour that showed a commitment to doing this,” says Valiente Riedl.

One in five Australians identify as having a disability, but this is not reflected in the workplace.

“Because we don’t have a lot of exposure to people with a disability, we tend to hold fears that we may offend them, that they might be less productive/reliable, or that there could be workplace safety issues involved.” – Daniel Valiente Riedl

Jessica Arthurson CPHR, assistant director, workforce strategies section at the Department of the Environment and Energy, understands the importance of disability diversity more than most. She dedicated her HR certification capstone project to creating a new stream to the department’s graduate recruitment program called GradAbility

The department originally allocated two spaces for those identifying as having a disability, but after receiving a flood of great applications it boosted it to four

“A lot of the time, people won’t know if they need an adjustment until they understand the requirements of the role. So we take the time to tell them about it so they can make an informed decision,” she says.

“The top candidate of the entire grad program was actually a GradAbility candidate and they would have been knocked out at round two had they gone through the general stream without any of the program’s adjustments.”

No flexibility

Another barrier, Findlay notes, is the lack of employers offering part-time options to disabled workers. While she works part-time in her current role with Melbourne Fringe (the other days allocated to freelancing gigs), her previous employers haven’t been as accommodating.

Findlay recalls asking for a part-time load on two occasions, once to pursue her freelance work and another time due to health reasons. When she was quite young, she was told by an employer that maybe she could “get pregnant and then you’d be able to work part-time”.

Valiente Riedl highlighted this as an important area for employers to improve upon. “I myself have two young kids and I wonder why the conversation is different when I need some flexibility in terms of my parenting role than if I had a mental health condition. Suddenly that conversation becomes very different, and it shouldn’t be,” he says.

Meaningful opportunities

When you speak to people about disability employment, the same thing is always brought up: the importance of providing meaningful work opportunities for people with a disability. The benefits of this are (hopefully) obvious.

What is meaningful work? It helps to define that by what it’s not. Findlay is particularly concerned about ‘jobs’ for people with an intellectual disability that, she says, don’t pay much because they’re categorised as a ‘community program’. She cited a case of people sifting through pig faeces to find worms for fish bait.

Derek Brown, the manager of the organisation that facilitates the worm bait program, Orana Riverland, spoke to ABC Online. “We do a lot of work that other people don’t want to do.” While he certainly meant “our workers are willing to give anything a go”, his comment also highlights something potentially troubling. If “other people” don’t want to do it, does it mean we think it’s appropriate work for people living with a disability?

“These jobs are degrading and the people in charge justify it by saying, ‘They wouldn’t be anywhere else. It gets them out of the house.’ But non-disabled people would never be asked to do that kind of stuff,” says Findlay.

When asked if she had a message for Australian HR practitioners, Findlay’s response was straightforward: “Don’t underestimate us. Hire us. Pay us.”

This article originally appeared in the Dec/Jan 2019 edition of HRM magazine.

Photo credit: Proud Haus

Drive inclusion and diversity outcomes in your organisation by raising awareness of both conscious and unconscious bias and its impact on decision making at work, with this Ignition Training course ‘Managing unconscious bias’.

As a workplace Diversity and Inclusion champion with lived experience of disability I thank you for your eloquent representation. To my HR colleagues, there are many talented individuals who struggle to find employment because of assumptions/hesitation/fear of employing those with disability. As HR practitioners we have a platform to assist our clients to extend their selection pools, through tapping into the considerable talent available through Job Access which specifically connects employers with job seekers with impairment/disability. One way to potentially break down those barriers may be by participating in 1-day work experience trials through AccessAbility Day. Help me to spread… Read more »