Investing in refugee talent can elevate your business, but organisations must first remove the barriers holding this group back. Here are four fresh ways to make that happen.

Trigger warning: This article on refugee talent mentions violence which might be distressing to some readers.

On a hazy morning in October 1999, Republican Guards stormed into Baghdad’s Saddam Hussein Medical Centre with three busloads of army deserters. Professor Munjed Al Muderis, then a trainee surgeon, was ordered to commit the unthinkable: mutilate the army evaders by amputating their ears.

“The head of the department openly objected, so they took him outside and put a bullet in his head in front of everybody,” Al Muderis recalls. “They turned to the rest of us and said, ‘Anyone who agrees with him should come forward, otherwise proceed with your orders.’ That was the most challenging moment in my life.”

Al Muderis could obey the commands and live with guilt for the rest of his life, or refuse and suffer the same fate as the department head. Fortunately, he didn’t settle for either option. Fearing for his life, he hid in the women’s locker room. When it was safe to do so, he emerged and prepared to flee Iraq.

After a gruelling journey, with 150 asylum seekers crammed onto one rickety boat, Al Muderis landed on Christmas Island, and then in the Curtin Detention Centre in the Kimberley.

Nine months later, he was released, and secured his first job as a toilet cleaner while waiting for his medical qualifications to be recognised in Australia.

Nearly three months later, in November 2000, he began working as a surgeon in Wollongong, NSW.

Al Muderis will expand upon his experiences later this month at AHRI’s Diversity and Inclusion Conference, held in Sydney, and online for virtual attendees.

Want to hear more from Munjed about the value of embracing refugee talent? Then book your spot at AHRI’s D&I Conference.

Unfortunately, Al Muderis’ keynote address, and the topic of embracing refugee talent in Australia more broadly, has recently re-entered the headlines in light of the humanitarian crisis currently sweeping through Ukraine. Since February, when Russia’s invasion began, more than 4000 Australian visas have been issued to Ukrainians.

Beyond providing a safe sanctuary for refugees, regardless of their country of origin, it’s essential to support them as they adjust to life in a new country.

Engaging refugee talent in meaningful and sustainable employment can be achieved by thinking about migrant talent in four different ways ways.

1. View skills gap through a positive lens

When you walk into Al Muderis’ practice in Norwest Private Hospital in northern Sydney, it’s clear he has made an indelible imprint on his chosen profession.

Framed newspaper clippings detail the ordeals he endured as a refugee and his remarkable contributions as an orthopedic surgeon and human rights advocate. He is a pioneer in the field of osseointegration, which involves implanting a prosthesis into the skeleton, and regularly returns to Iraq to help amputees to walk again.

When Al Muderis reflects on the innumerable benefits that refugees bring to Australia, he could very well be talking about himself.

“A lot of people who come to this country will work 10 times harder than if they have been living in the same place for a long time.”

While the absence of certain skills might be viewed as a gap, this could also be reframed through a more positive lens.

“[Many] refugees could have significant difficulty with English, but they also have a strength. They know at least one other language and that can be harnessed. There are always treasures inside people’s brains and you need to invest in them.”

Approaching refugee recruitment with an open mind is key, especially in a tight labour market, says Padmi Pathinather FCPHR, General Manager, People and Culture at Settlement Services International (SSI), a not-for-profit organisation that helps refugees, asylum seekers, migrants and newcomers settle in Australia. SSI was recently awarded for its work in the D&I space at the 2021 AHRI Awards.

When there have been educational gaps in a refugee’s skillset, SSI has had great success in helping refugees access education and secure sustainable and meaningful work upon their arrival in Australia.

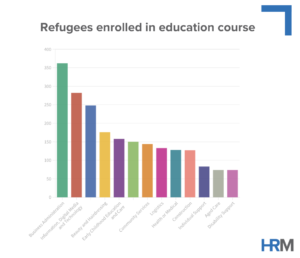

Since SSI’s Refugee Employment Services Program (RESP) began in mid-2017, 2700 refugees have been enrolled in an education course. This amounts to 32 per cent of the RESP client base.

Source: RESP, SSI.

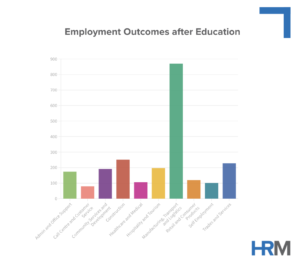

Of this cohort, 2600 refugees (31 per cent of the RESP client base) have secured employment after undertaking an education course. The below graph indicates the top industries that refugees engaged in RESP have entered.

Source: RESP, SSI.

“Australia is a very multicultural community,” says Pathinather. “If organisations want greater access to certain communities, this can be enabled by having employees who speak a second language.”

2. Rethink existing processes

Skilled workers from overseas – whether migrants, refugees or asylum seekers – often run into difficulty when trying to have their overseas qualifications recognised in Australia.

It’s why the Global Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications concerning Higher Education is imploring the Australian government, and other countries, to ratify a United Nations convention which would give greater assurance to migrants that their overseas university qualifications will be recognised.

On an industry level, it might be possible to validate overseas accreditations more easily, but this may require a more fundamental shift in attitude.

“Many professions… want to guard themselves from anyone claiming the status of being able to do X, Y and Z so they have that exclusivity of professional status,” says Dr Betina Szkudlarek, Associate Professor in Management at the University of Sydney Business School (USBS).

“But how much of a real difference is there between being a nurse or a designer in Australia, Korea and Afghanistan? The question is: in some professions – and there are many of them – can we create accreditation processes that are inclusive?”

Often, industries and employers are reluctant to adjust their entry processes because of discriminatory attitudes, says Szkudlarek, who recently wrote The Employers’ Guide to Refugee Employment, published by the USBS and Crescent Foundation, with Dr Jeannie Lee, Lecturer in Management at Newcastle Business School.

Szkudlarek says most organisations believe their workplaces are free of discrimination, but prejudice is often playing out in subtle ways.

“Some candidates find that including a qualification from a foreign university works against them. Social welfare organisations that work alongside refugees are aware of those prejudices and advise refugees to remove foreign qualifications from their resumes.”

But that elimination comes with a price – including the removal of impressive credentials, says Szkudlarek, leading refugees to have to build everything from scratch.

There are other barriers that can prevent refugees from securing employment in Australia, says Lee, including the absence of local connections and knowledge of Australian customs, and speaking English as a second language.

These hurdles led Lee and colleagues to coin the term “canvas ceiling” – a concept that draws from the notion of a glass ceiling, and refers to the temporary tents set up in detention camps.

“Even if they get out of those temporary camps and find refuge in a receiving country like Australia, they’re still metaphorically trapped in those temporary camps,” says Lee. “It’s very difficult for them to climb up the ladder or entirely remove themselves from those tents.”

“We need to broaden our thinking because bringing refugees, asylum seekers and migrants to Australia is the only way we’ll be able to inject talent quickly and overcome the shortage.” – Padmi Pathinather FCPHR, General Manager, People and Culture Settlement Services International

Breaking through the canvas ceiling starts with recognising refugees’ unique expertise and determination.

They are usually very determined to rebuild their lives and create the “sense of normality” that was robbed from them, says Szkudlarek.

“It’s not like they can change their mind and say, ‘I gave it a try and now I’ll go back.’ Quite often, there is no point of return. Many refugees are applying for job after job after job… They’re often in a negative headspace, having put a lot of effort into the job search process but not getting a single response.”

So when a job offer comes their way, they’re unlikely to let it pass by and will often go above and beyond to “prove themselves and show the employer they made a good decision”.

3. Build dedicated programs to engage refugee talent

Many organisations that have set up short-term refugee employment programs have forged strong relationships with members of multicultural communities, be they customers, clients, suppliers or job candidates. The common heritage can create a strong sense of shared identity.

IKEA launched its ‘Skills for Employment’ initiative in October 2020, and project leader Harriet Pope says it has shown “clear examples of a deep cultural understanding and shared languages between many refugee employees and [IKEA’s] customers”.

“That leads to a better customer experience, especially in some of the more diverse markets across the country.”

The program provides refugees with a two-month paid work placement and operates in every IKEA store in Australia.

“It’s an opportunity to create new social and professional networks, build on existing skills and improve English confidence,” says Pope. “We want to help create a bridge between the situation that people find themselves in and where they have the potential to be.”

Pope attributes the success of IKEA’s program to the partnership formed with Community Corporate, a social enterprise organisation that provides services such as developing a shortlist of participants, verifying the working rights of participants and delivering pre-employment training for refugees.

Before finding a suitable provider, it’s best to home in on the skills your business requires, says Lee.

The service and/or training provider can then work with your business to co-create a refugee employment program.

In IKEA’s case, Community Corporate created customised cultural awareness training for the program buddies – existing employees who are paired with a refugee throughout the program – and line managers who are responsible for supporting refugees in their new roles.

The cultural awareness training “focuses on the refugee experience, barriers they face in Australia, supporting those who may have English as a second, third or even fourth language, and building rapport”, says Pope.

“It’s still in its early days, but we are seeing early indications of significantly lower turnover and absenteeism… We’ve unearthed a new talent pool of highly motivated, adaptable and loyal people.”

4. Take a trauma-informed approach and consult community leaders

Being aware of the sensitivities around embracing refugees – many of whom have significant trauma in their recent histories – has been front of mind throughout the roll-out of IKEA’s program.

Many refugees arrive in Australia after witnessing unspeakable acts of torture. Others have survived natural disasters or seen their homes and cities destroyed. All have had their lives suddenly uprooted and are adjusting to life in a foreign country. They’re mourning the loss of their home, and often the loss of family members.

Employers should always keep this front of mind by adopting a trauma-informed approach, says Pathinather.

“When someone presents themselves for an interview, we need to keep in mind that they’re not just having to secure a job, but they’re also perhaps looking for affordable housing, or trying to settle their children into a new school, or they simply might not own professional clothing that’s typically expected for a job interview.

“They may be dealing with a greater emotional load than other candidates.”

“There are always treasures inside people’s brains and you need to invest in them.” – Professor Munjed Al Muderis, Orthopaedic Surgeon and Human Rights Activist

To understand refugees’ unique trauma backgrounds, employers could consult community leaders who understand the lived experience of refugees in their respective communities, suggests Pathinather.

“We engage with a number of Afghan community leaders in particular on a regular basis. We run a lot of forums and discussions with them so we know how to prepare for any newly arrived refugees.

“The cultural nuances and barriers to be aware of can form anything from etiquette to greetings to unique religious requirements.”

Forming authentic connections with various community leaders can help employers to respond to the unique needs of individuals and prepare for the arrival of refugee talent, to ensure a smooth transition into the Australian work environment.

“To drive successful employment outcomes, HR and other leaders in an organisation need to focus on listening to refugees, more than offering a solution. This will require unpacking the different layers of their trauma, treating them with respect, understanding their aspirations, drawing upon their strengths and giving them hope for a sustainable future.”

A version of this article first appeared in the April 2022 edition of HRM magazine.

Just a clarification regarding Ukraine. It is referred to as Ukraine, never the Ukraine. Thank you.

I was involved in educating refugees in Thai camps. They had been to Hell and back. Once they had their diploma they were able to travel. Many landed in Sydney and Melbourne. They now contribute wonderfully to their communities and remain eternally grateful to our government for making it possible.

Excellent article! Recognizing refugee/ migrant talent and developing inclusive policies is the best way to build a stronger more cohesive Australia