Some staff are fed up with poor quality co-workers, so much so they’re willing to quit despite the unstable job market. Is this just end of year blues or something bigger?

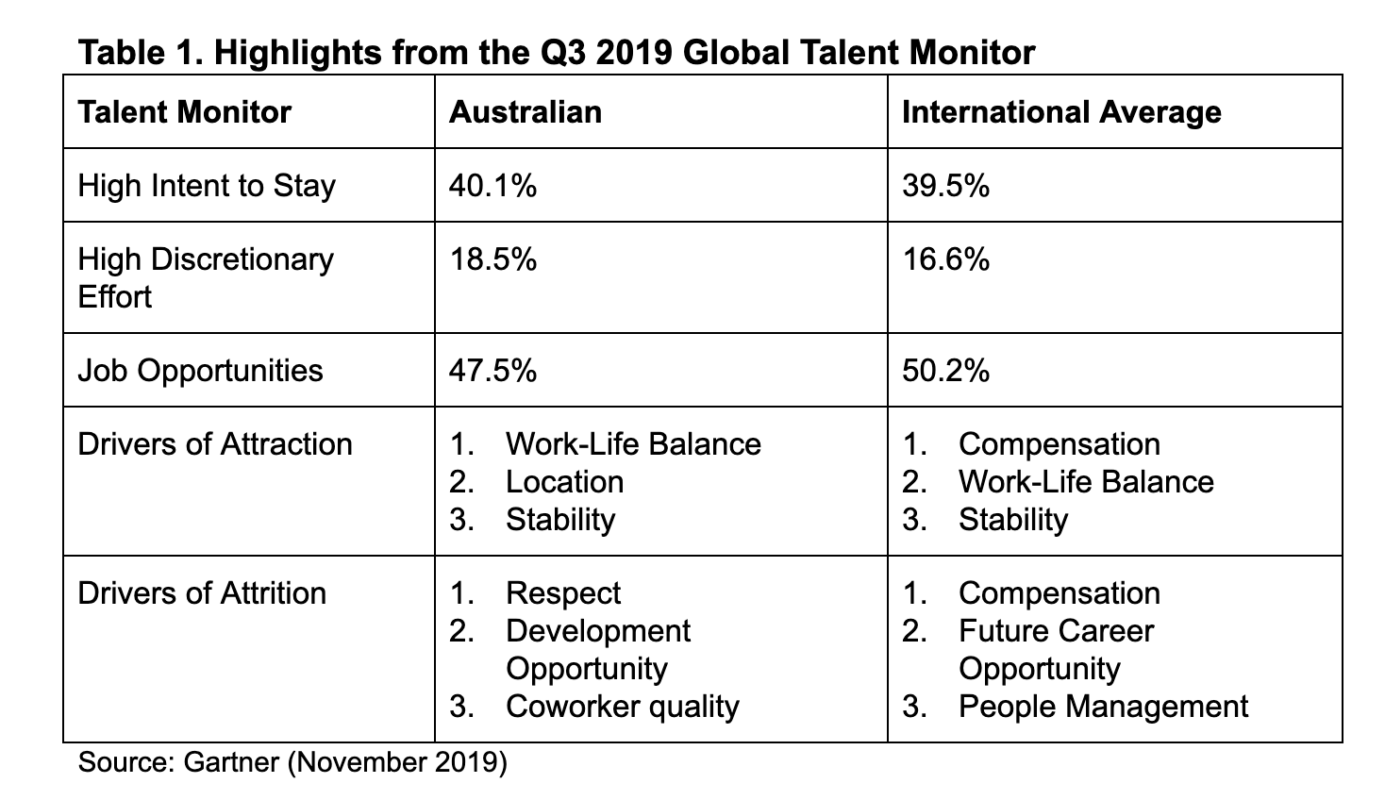

Australian employees have worryingly low engagement levels, a decrease in discretionary efforts and intent to stay with an employer, and a new focus on the quality of their colleagues, according to Gartner’s third quarter global talent monitor for 2019.

When it comes to drivers of attrition, ‘poor quality coworkers’ has risen eight positions since the previous quarter and now sits as one of the top three reasons staff would quit.

“Work is more interconnected than it ever has been,” Aaron McEwan, vice president research and advisor of Gartner tells HRM. “What that means is that the average person relies on their co-workers to get their jobs done. The saying ‘no man is an island’ has never been more true in the context of the modern workplace.”

Tensions are high

It’s not as if the underperforming staff have only just started doing so. It’s more that the patience of other employees is wearing thin at this end of the year.

“We have a stressed, stretched and overworked workforce,” says McEwan. “Staff are being asked to produce more with less and they’re not always getting recognised for that additional effort.

“It’s been like a sprint since the first of January. People are way less tolerant than they were [earlier in the year] in regards to bad behaviour from colleagues.”

McEwan says that low wage growth and a lack of promotional opportunities and development plans could also be a contributing factor.

“There are many employees who’ve been through more than ten years of cost cutting, transformations and organisational restructures. So you can imagine if someone wasn’t quite pulling their weight or putting their hand up, that could mean that a lot of the most critical work is left to a small percentage of employees who are doing the bulk of the high impact work.”

Pull all these factors together and you’ve got a troubling situation: some staff are willing to jump ship, even if they might fall into murky waters.

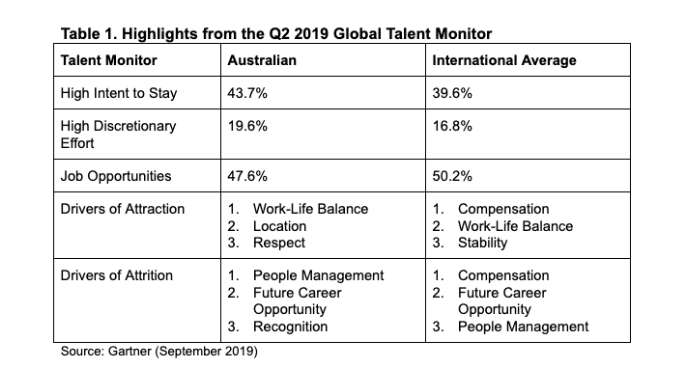

When HRM last spoke with McEwan to unpack the results from the Q2 Global Talent Monitor, job searching behaviour was low and discretionary efforts were high, but not for good reasons.

Back then, McEwan suggested a potential looming recession could have been to blame. Staff were fearful of losing their jobs, so they were buckling down to prove their worth. This time around, economic uncertainty hasn’t changed, but employee attitudes have.

“The most logical conclusion to draw here is that people’s dissatisfaction at work is outweighing their fears of an unstable job market,” says McEwan.

Then of course there’s the string of various business scandals that we’ve seen recently. People are overexposed to unethical behaviour and perhaps less tolerant of it.

McEwan adds: “The other factor that comes into play is that people are less reliant on their managers. They aren’t the critical focal point of organisations like they used to be. We spend more time with our co-workers than we do our managers.”

So when they’re not up to scratch, employees really notice.

What else has changed?

As was true of last quarter, Australia sits above international averages for effort and ‘intent to stay’, but as you can see from the two tables below, other things have shifted.

While in the last quarter staff were seeking more recognition, career opportunities and better people management, now a lack of respect has taken the lead as the top attrition driver, followed by a lack of development opportunities and coworker quality.

This quarter’s results also found that only 11.2 per cent of staff feel engaged and, not surprisingly, these are the staff with the highest discretionary effort and intent to stay with their companies.

A new approach to performance management

Combatting underperformance is critical, says McEwan. Managers need to call it out and coach staff to do better.

One way to do this, McEwan says, is to re-think our approach to performance management. Instead of focusing on individuals, he believes we should be performance managing teams.

“Remember those group assignments that you had to do at university? People hated them because there was always a couple of people who didn’t show up or didn’t do any work. That’s what our workplaces look like.

“A lot of organisations use forced distribution approaches to individual performance management. But our research clearly points to the benefits of producing high-performing teams. Employers need to have a more conscious focus on how to lift the performance of a team rather than lifting the performance of an individual and hoping it correlates with high performance overall.”

McEwan says it’s still important to acknowledge and reward the individual efforts of those who go above and beyond, but performance management as a whole should be looked at from a team lens.

But you can’t foster high performing teams through management alone, you also need psychological safety.

“Managers need to create an environment where their staff feel safe to call out underperformance. That’s a really challenging conversation to have if you don’t feel like you have the permission to address these issues. People are choosing to leave, rather than having those challenging conversations.”

Some of these employee gripes might seem insignificant or fleeting, but they’re not. To reiterate a point made above, staff are becoming so fed up that they’re willing to jump into an uncertain job market just to escape. This fact should be ringing like an alarm bell for employers.

Gartner has a wealth of valuable research that AHRI members can access for free. Find out more here..