You can’t stop at offering employees a psychologically safe workplace – that’s just a basic expectation. Here’s how to take it to the next level.

Psychological safety is a commonly discussed topic at the moment, and rightly so. Most employers understand that in order to get the best out of people, they need to provide an optimal psychological environment in which they can flourish.

This sense of safety is about giving permission for candour and inviting people to welcome bad news, says Amy Edmondson, Novartis Professor of Leadership at Harvard Business School and the researcher who put team psychological safety on the map in the 1990s.

“Psychological safety describes an environment where you believe you can offer ideas, ask for help or report a mistake without negative repercussions.”

Why does this matter? That is the million-dollar question. Or rather, the billion-dollar question.

Mentally unhealthy workplaces cost the Australian economy about $60 billion a year, according to Deloitte. While there are plenty of factors contributing to this – such as stress from the pandemic, or our increasing tendency to overwork – research from the University of Pennsylvania shows that feeling like you can’t speak up at work also has significant impacts on wellbeing, as it can increase our likelihood of burnout.

Low levels of psychological safety also tend to result in less innovation, as employees are unlikely to share their half-baked ideas, or point out errors they notice. In the best-case scenario, that could mean you miss out on a revenue-generating idea. In the worst-case scenario, it can open you up to safety risks.

In short, if you want a thriving, innovative workplace culture, you need a foundation of psychological safety. However, it is just that – foundational. Employers don’t get a pat on the back for simply catering to their people’s baseline psychological needs. That would be the equivalent of an employee arguing they should be paid simply for showing up to work.

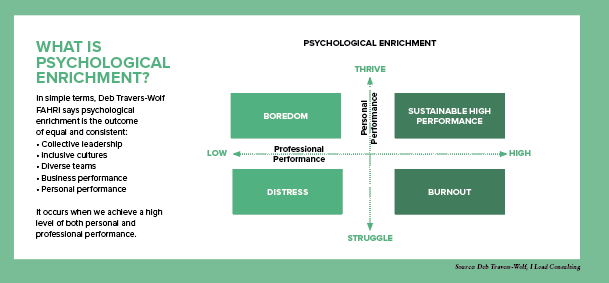

“Psychological safety is just one dimension, albeit an important one, that we need in our workplaces,” says Edmondson. The way to think about it, she says, is as a means towards excellence. It’s what HRM is calling psychological enrichment – the things that motivate, challenge and inspire us at work.

“There are different ways of thinking about the fuel that motivates us to exert ourselves,” says Edmondson.

What enrichment looks like for one person will be completely different for another. Someone might want their employer to help them live a healthier lifestyle, for instance; whereas enrichment for another person might look like sinking their teeth into a fascinating project that requires them to learn about something completely different from their ‘day job’.

“When I think of psychological enrichment, I think of a garden,” says Deb Travers-Wolf FAHRI, founder of I Lead Consulting.

“I’ve got this big row of plants I’ve been looking after for about three years now. I’ve watched them thrive then not thrive, and I try to figure out what the consistent factors are.”

There’s no silver bullet for psychological enrichment, she says. It’s built upon a collection of purposeful acts.

However, one of the key elements, she thinks, is intentional inclusion efforts.

“Every time I slice and dice data, psychological safety, engagement, inclusion, belonging, whatever dimension you analyse, is reduced for diverse and under-represented populations. You’ve got to try to ensure everyone is having consistent experiences equally. When I look at that line of plants, they’re all equally thriving. Not just one or two that have had more sunshine or water.”

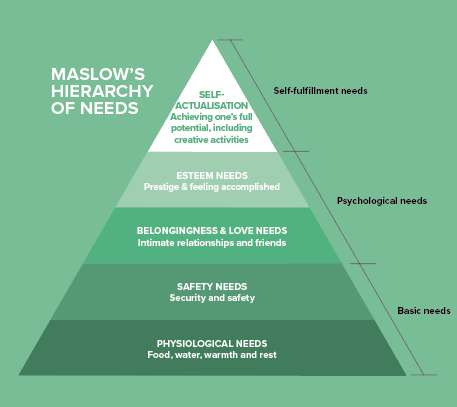

Lynda Edwards, Director of Consulting Operations and Insight Design at the NeuroLeadership Institute, points to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to demonstrate the difference between psychological safety, which exists in the lower two sections of the pyramid, and psychological enrichment, which kicks in from the third level up.

“We need psychological safety to survive,” says Edwards. “If we think about the neurobiological response in terms of threat and reward, when people aren’t psychologically safe, they’re sitting in a threat state. In this state, their cognition is impacted, their creativity is impacted, their perception is impacted. And collaboration – playing nicely with others in the sandpit – doesn’t happen.”

It’s the flight-or-fight state. If people feel in threat, which many would right now when you consider the world we are living in, they’re potentially going to hunker down and hold back.

“That can encourage protectionist-type behaviours. They’re not tapping into their discretionary effort. They’re not going to add as much value. They might feel defensive and they’re not going to feel fulfilled.”

Helping an employee to feel enriched doesn’t just mean eliminating the threats, says Edwards. You have to “take it to the next level”.

“I think of it like those regenerative practices from farming – leaving the earth better than we found it. We need to think about this in terms of talent and leadership. How can we provide a sense of enrichment to our people so we leave them much better than when we found them?”

From psychological safety to a thrive state

A psychologically enriched workforce will equal greater innovation, engagement, retention, business outcomes and a bigger competitive advantage, says Edwards.

“You’ll have people who feel more valued, have greater wellbeing and resilience, and they’ll be more motivated, which we know has significant positive health outcomes. All of that can be translated to the bottom line.”

This might sound obvious, but despite the clear win for businesses, many organisations are still struggling to get to this ideal state. That’s most likely because dealing with a collection of individuals and their respective needs and challenges can be tricky. But it could also be because some employers are stopping at the start point.

A workplace that’s free of toxic behaviours such as bullying, harassment or gossip is not inherently enriching. It’s standing at the beginning of that journey.

It’s about setting high standards, facilitating impactful motivation and having a shared ambition or purpose, says Edmondson.

“I also think we as human beings want to be stretched so we grow. That feels good because we have something hard to do that we can eventually master,” she says.

“Even if that’s taking a process we currently have and making it just that tiny bit better. We get that feeling of ‘I got well-used today.’”

This important sense of mastery or purpose could be achieved through a process known as ‘job enrichment’. It’s a concept popularised by psychologist Frederick Herzberg in the late 1960s, whereby an employee’s work is altered in a way that makes it more stimulating or challenging, so they can learn new skills and stretch themselves.

Importantly, job enrichment isn’t the same as job enlargement – i.e. simply expanding an employee’s remit – which could result in further disengagement, burnout or increased intention to quit.

Building off Herzberg’s work, in 1976 psychologist J. Richard Hackman and economist Greg Oldham developed the Job Characteristics Model, which has since been used as the basis for job enrichment strategies. It includes five pillars:

-

- Skill variety – increasing the skills an employee uses (or needs to learn) to do their job.

- Task identity – seeing a project through from start to finish to feel a sense of ownership.

- Task significance – offering work that has a strong sense of purpose to the individual, organisation or other important stakeholders.

- Autonomy – allowing employees to take on more decision-making power and giving them the freedom to choose when and how the work is completed.

- Feedback – ensuring consistent, regular recognition of good work is shared throughout the organisation.

Neel Doshi, co-founder of Vega Factor, former partner at McKinsey & Company and author, might offer a sixth point to that framework: experimentation.

“Experimenting in your work is actually a lot of fun,” he says. “It’s very motivating.

If you have a job where you feel you can try things, see what works, try something different, and feel creative, you will be much more motivated to do that work.”

When we go into crisis mode – when our physical, emotional or psychological safety is threatened – we tend to lean towards tactical work (rote tasks), he says. What people need to feel motivated is to engage in adaptive work (work that engages our creativity and ingenuity).

“How can we provide a sense of enrichment to our people so we leave them much better than when we found them?” – Lynda Edwards, Director of Consulting Operations and Insight Design, NeuroLeadership Institute

The trouble is, a thriving organisation requires a healthy balance of both sides. People need to be able to solve problems and challenge themselves, but tactical work is still required.

“Imagine if the building is on fire,” Doshi previously told HRM. “People don’t want you to empower them to find the door. If it’s a genuine crisis, they want you to just tell them how to get out.”

Many employers misdiagnose the moment they’re in, he says. They always think the building is on fire. Therefore, they might double down on the rules or tighten employee freedoms and, often without realising, they smother the last lick of the flame that is that individual’s sense of experimentation.

Leaders often don’t have the confidence to try new things in crisis, says Travers-Wolf.

“When leaders are fearful, they play it safe, which makes exploring and experimenting really hard. But we know from research on high-performance teams that being able to explore far and wide increases not only our own performance, but our own intelligence.”

Experimentation leads to a stronger sense of motivation. To demonstrate how impactful this can be on an individual and organisation’s sense of enrichment, Doshi uses the example of a call centre he worked with.

“The opposite of purpose is fungibility – when you feel you’re easily replaced. These days, call centres are designed to make [workers] completely fungible. You sit down, log into the phone system and then a customer is in your ear. The moment you log off, it’s really no big deal because your calls are automatically redirected to hundreds of other call centre workers.”

“We as human beings want to be stretched so we grow. That feels good because we have something hard to do that we can eventually master.” – Amy Edmondson, Novartis Professor of Leadership, Harvard Business School

Doshi and his colleagues worked with a call centre in the insurance industry to increase employee motivation through experimentation.

“These are big football field-sized rooms with thousands of people, many of whom are in a low-play, low-purpose state,” he says.

They asked the workers to identify the things they wanted to improve and made sure they were engaging in experimental work every week to solve these specific pain points.

“It took us a few weeks to set this up,” says Doshi. “But within a week of working this way, a frontline call centre rep came up with a multi-million-dollar idea. This kind of stuff happens all the time.”

We need to work together

Job satisfaction and psychological enrichment shouldn’t just sit on a leader’s shoulders alone, says Edwards.

“Co-creation around things like this is important,” she says. “This approach does a couple of things. Firstly it tells people that they’re valued and that they’re masters of their own destiny. It gives employees autonomy to plan their work or the projects they want to work on, or to take on that volunteer opportunity, for example. We want to give people a sense of ownership and empowerment.”

This is more likely to offer enrichment to an employee than taking a prescriptive route, she says, because if you assume you know what people need, there is a good chance you will get it wrong.

“You need to be asking them questions like, ‘What would it look like for you to get more from your work and fill your cup?’

“Remember, sometimes it won’t be about climbing the ladder. It could be being able to lean in and add value to something they feel strongly about, such as a particular project or part of the business.”

We can’t forget that our organisations are made up of living things, says Edwards.

“It’s about enriching the individual and growing them in many ways, enriching the team through cross-skilling and enriching the organisation in terms of diversification.”

This people-centric mindset is what has got businesses through the pandemic so far. And it will be the mark of a successful business strategy moving forward.

If all you do is plant the bulbs, dust off your hands and call it a day, you’ve got little chance of creating a thriving garden. You need to constantly tend to it and respond to its changing needs in order to see it blossom.

A longer version of this article first appeared in the October 2021 edition of HRM magazine.

AHRI has a suite of fantastic health and wellbeing resources available for its members. Browse them all here.

Great article – jam-packed with some key messages on how to create a thriving workplace culture!