Safe Work Australia has announced its plans to create safer workplaces by reducing fatalities by 30 per cent over the next decade. But does this workplace health and safety strategy go far enough?

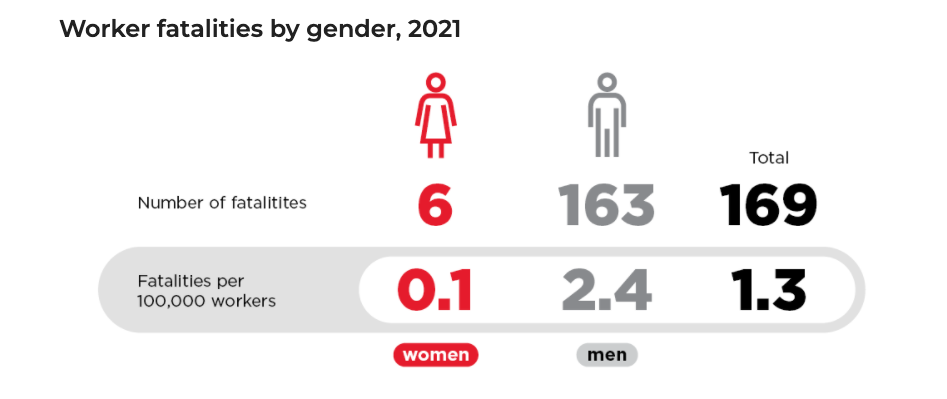

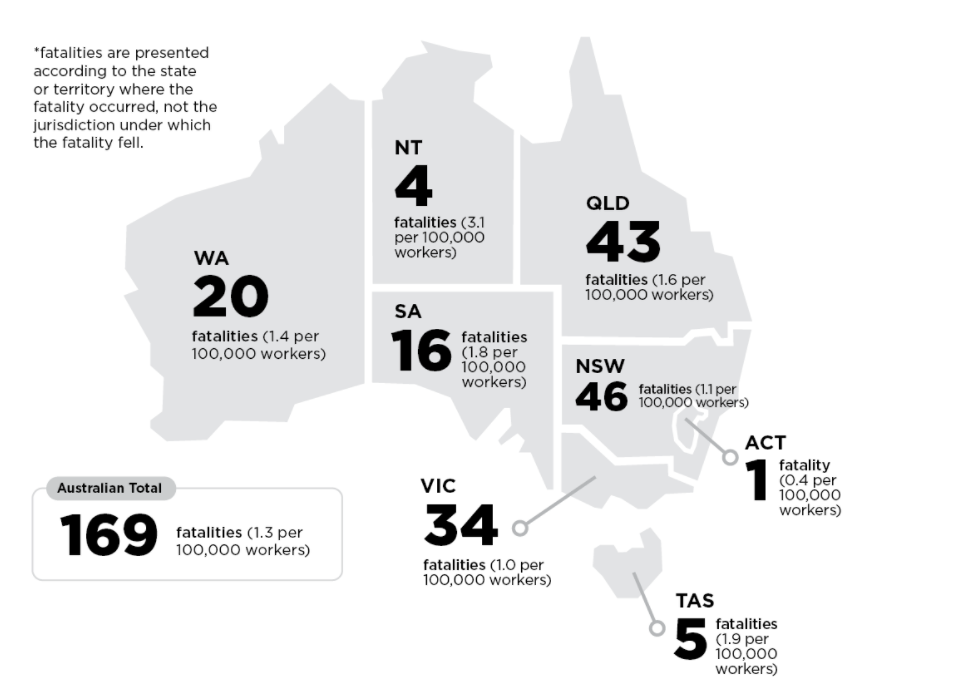

Nearly 170 Australians lost their lives due to a workplace fatality in 2021, the majority of which were male workers, according to the most recent statistics from Safe Work Australia.

Safe Work Australia is committed to reducing that number by 30 per cent over the next ten years, as part of its recently released Australian Work Health and Safety Strategy 2023.

As well as reducing fatalities, the safety agency is looking to reduce serious workplace injuries and illnesses (that is, those that result in one or more weeks off work) by 20 per cent, with workers compensation claims hitting 130,000 in 2021.

Despite fatality numbers steadily decreasing over the years – we’ve seen a 57 per cent drop since 2007 – 170 lives is still 170 too many. There’s also an economic benefit to reducing accidents and fatalities – estimations suggest these incidents cost Australia over $60 billion per year.

On top of this, Safe Work has seen a worrying rise in psychological injury claims in recent years, which can often lead to suicidal ideation in workers or pose serious risks to employees’ long-term mental health. That’s why, as part of the 2030 strategy, it’s putting psychological hazards on the table for discussion.

Emerging workplace health and safety risks to keep on HR’s radar

When you look at the most common causes of workplace fatalities, it’s likely what you’d expect: falls, vehicle incidents, mental health concerns etc. See the full list in the graph below.

The industries classed as ‘high-risk’ are also unsurprising. Seventy per cent of injuries occur in agriculture, construction, transport, manufacturing, healthcare and social assistance or public administration and safety – the majority of which are male-dominated industries.

While there tend to be fewer plans in place to tackle psychosocial hazards, they are still on many organisations’ radar, which is important when you consider there has been a three per cent increase in mental health claims from 2014-15 to 2020-21.

Most savvy employers, especially those in high-risk sectors, will have prevention strategies in place to mitigate these challenges. However, there are also some new and emerging risks that employers will need to start factoring into their existing workplace health and safety policies and processes.

They include:

- The rise of AI, technology and automation – while this could help free up the human workforce from some of the more mundane work, it also has the potential to cause burnout and other psychological hazards. For example, it could lead to a culture of overworking, as this technology will undoubtedly assist in churning out higher volumes of work, most of which will still need a human touch.

Moreover, technology like the metaverse is already accruing claims of bullying, harassment and ‘virtual assault’.

- Climate-related risk – as well as obvious risks such as increased flooding, bushfires and severe winds, it’s also worth having a strategy in place for working in the heat, which will increasingly become a challenge in certain roles, such as construction workers who are out in the sun all day. (Here is a guide with helpful information on this.)

- Hybrid working – this could include incorrect set-ups for workstations, overworking and a lack of oversight for risk management from the employer.

- New workforce demographics – as Australia’s workforce ages, we run the risk of an increase in serious, long-term injuries occurring in older workers. In industries that hire a lot of migrant workers, some of whom may not understand English clearly, we also need to ensure that safety briefings, risks and training are communicated clearly.

Is HR adequately prepared?

Ciaran Strachan, Managing Director and CEO of the Australian Workforce Compliance Council, says HR leaders and employers need to understand the difference between fiduciary responsibility (legal and ethical), capability and accountability.

“The WHS Act now has a strategy to be executed nationally by private organisations and Commonwealth regulators. However, under the Fair Work Act, every agreement and Award must have a grievance process,” he says.

“Are you prepared for not only a bullying/harassment complaint, but also a sexual harassment complaint which now carries with it a positive duty? In plain English, the employer must satisfy the burden of proof that it had an effective grievance process in place and psychosocial hazard management controls, both preventative and responsive.”

“We have a long way to go for safety and IR to effectively integrate.” – Ciaran Strachan, Managing Director and CEO of the Australian Workforce Compliance Council

Importantly, Strachan adds that not all HR professionals currently have the necessary expertise, experience or qualifications to investigate safety hazards.

“Many high-risk physical sectors, such as mining, have dedicated investigators, many of whom have qualifications in investigations and – for those who frequently represent their employers or clients in front of the FWC – are qualified mediators.”

Without this dedicated in-house support, he suggests engaging the services of a qualified contractor to ensure your organisation is operating compliantly.

What is the strategy proposing?

The main objective set out by the strategy is to increase awareness of employers’ duty of care to protect their workers from physical and psychological harm at work (namely those running small businesses, which account for 43 per cent of employees with higher injury rates).

It also aims to build awareness around managing psychosocial hazards. Safe Work is set to release a new Code of Practice later this year for further advice on this.

You can view Safe Work’s full strategy here, but here are some of the main points:

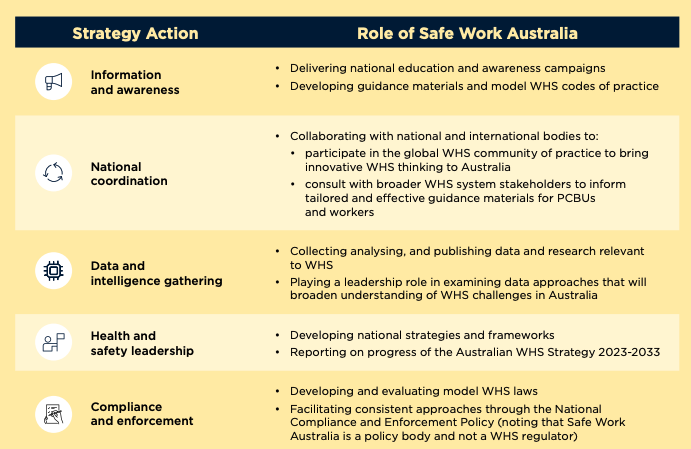

- Increasing information and awareness

Safe Work feels there’s a lack of public awareness around psychosocial risks and how to weave them into a WH&S approach. The strategy includes the creation of compliance checklists, consultation with small businesses, training supplied for knowledge gaps and targeted support for high-risk industries.

- National coordination (i.e. helping companies that operate across multiple jurisdictions)

This will include various states sharing their success stories, so initiatives can be replicated and scaled elsewhere with the aim of an eventual best-practice national framework. Safe Work also recommends engaging with national employers to learn more about the challenges they face when navigating state-based laws.

- Data gathering to see the full-picture of the issue

Safe Work aims to collaborate with government, social partners and researchers to ensure that national surveys and other data collection efforts include WHS measures and occupational information. - Health and safety leadershipSafe Work plans to engage with the training sector (vocational, tertiary, private etc.) to influence the way in which future health risks are taught, and to promote WH&S careers, such as occupational hygienists and physicians.

- Compliance and enforcement

The strategy suggests targeting national compliance and enforcement campaigns to poor-performing and high-risk sectors. It also seeks to develop insights from data on prosecutions, notifications and breaches to increase knowledge-sharing across the WHS system.

“The real standout for me is the increased focus on data, such as insurance claims, which was previously ignored, and expanding the focus from physical safety management [to include psychosocial risks],” says Strachan.

“However, I don’t yet see a clear path for anybody wearing both the ‘Fair Work’ and ‘safety’ hats, as the strategy appears to be lacking the mechanism to deliver on the expectations of psychosocial hazard management. This requires a combination of risk management and the Fair Work grievance process, which is more often than not used to manage psychosocial hazards including allegations of bullying, yet treated as separate from safety.”

Strachan’s recommendation for those responsible for managing risks is to combine the capabilities of both to ensure all processes are integrated.

“This means HR does not exclusively own all allegations of bullying/harassment, nor does safety. However, neither should be excluded. In my opinion, best-practice would be for all complaints or allegations to be referred to an independent and qualified workplace investigation [professional] – whether that be for minor situations requiring only workplace mediation, or more serious situations that require an official workplace investigation.”

Strachan is also concerned by other gaps that he sees in the strategy, including:

- A lack of focus on the operational side of the strategy.

“If we look at the tax system, the Australian Tax Office has free standards (Australian Accounting Standards Board), a series of regulated professions or self-regulation via a professional regulator, yet there is nothing like this for safety,” he says. “Safety standards are generic… both safety and HR are not regulated, and therefore the line-by-line expectations of their professions are not benchmarked according to the government, and in turn Safe Work Australia’s expectations.”

- A lack of integration regarding psychosocial hazards.

“Although Safe Work Australia sits in the same portfolio as the Fair Work Commission, as well as the National Workplace System, I see no sign of consultation on the joint issue of psychosocial hazard management as of yet. Meaning, we have a long way to go for safety and IR to effectively integrate.”

Safe Work’s desired outcomes

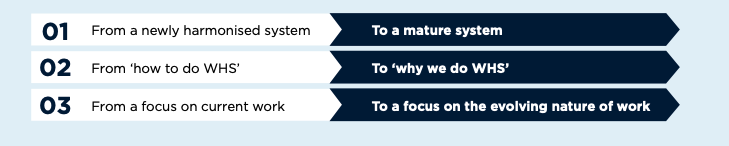

By 2033, the end goal for Safe Work Australia is that the workplace health and safety landscape will look something like this:

The soon-to-be released psychosocial hazards Code of Practice and the Australian-first construction silica Code of Practice are set to share further insights into how Safe Work Australia, in partnership with industries, can meet these ambitious yet critical fatality and injury reduction targets.

The hope is that Australia will soon have increased collaboration between state and federal governments (i.e. coordinated compliance and enforcement and national awareness campaigns), and a national WH&S model that is updated in a timely way with replicated/scaled prevention methods.

Since 2012, when Australia’s workplace health and safety laws were first harmonised, we’ve seen a steady drop in both fatalities and claims, but now it’s time to go further and create even safer workspaces.

Learn how to develop effective workplace health and safety processes by signing up for AHRI’s short course, ‘Developing policies and procedures’.