Over the years, work has demanded more and more of our time, leading to the rise of ‘greedy work’ and a wider gender pay gap. Could the pandemic bring about a change for the better?

Australian employees are engaging in obscene amounts of unpaid overtime. They’re letting work bleed into their leisure time. And they’re burning out at extremely worrying rates.

While we often think about these things from a wellbeing perspective, it’s also worth looking at it from a gender perspective, too.

For working couples with children (currently around 4.3 million couples in Australia), if one person is engaging in gruelling work hours, that means the other person has to be home in time to defrost the lasagne and draw the bath. Often (but not always) that person is female.

Often these jobs with demanding hours are what experts call ‘greedy work’, sometimes referred to as ‘greedy organisations’.

Greedy work rewards those who put in really long hours with high salaries. Think of the high-powered lawyer working on the weekends or the business executive who spends a large portion of their year jetting off from country to country (at least they would have pre-COVID-19).

“The employee who is willing to work at all hours – in the evenings, on weekends, on vacations… is the worker who gets the bigger rewards. When these rewards are disproportionate to the time put in, meaning that doubling the time more than doubles the earnings, we get ‘Greedy Work’,” says Claudia Goldin, Harvard economic historian and labor economist, in a podcast for Princeton University Press.

Organisations operating in the finance and banking sectors, and larger law firms, are particularly ‘greedy’, says Goldin.

“It isn’t necessarily the number of hours [either],” she says. “It is often ‘which’ hours (weekend, vacation, dinner time, evening). And the relationship can also be dynamic and be part of the “up or out” system common to many high-end employments. Work more now, and get big rewards in the future – e.g. partner, tenure, first promotion.”

Goldin, who has been studying gender pay gaps for decades, says her research indicates that women are more likely to work in firms that are less demanding of their time – ergo, greedy work attracts more men, which further expands the glaring gender pay gap.

“Why can’t dual-career families share the joys and duties of parenting equally? They could, but if they did, they would be leaving money on the table, often quite a lot. The 50-50 couple might be happier but would be poorer,” she says.

In Australia, industries such as finance and medicine are particularly prone to greedy hours, says Marian Baird AO, Professor of Gender and Employment Relations and Head of the Discipline of Work and Organisational Studies at the University of Sydney.

“It’s those highly specialised industries where this expectation of long hours is a mark of surviving… and [the narrative is] that if you can’t hack it, you have to get out,” she says.

“Why can’t dual-career families share the joys and duties of parenting equally? They could… the 50-50 couple might be happier but would be poorer.” – Professor Claudia Goldin, Harvard economic historian and labor economist.

So what’s driving this trend?

“My thinking is that it goes back to the 1980s,” says Baird. “We saw an explosion of high pay and bonuses to people in certain industries, especially in finance. This surprised people at the time. People then [felt they had to] justify why they got such huge bonuses.

“They’d think, ‘I have to work for this’ so they’d get into a cycle of working really long hours.”

This was influenced by the rise of the lean organisation, she adds, which stripped away managerial levels in businesses, and “put enormous pressure on those remaining”.

This arose from improvements to manufacturing processes in Japan, says Baird, which demonstrated how an organisation’s processes could be streamlined. We learned how to do more with less, stretching employees very thinly in the process.

“What’s also [influenced this] is that we’ve seen much greater wage or salary dispersion in countries like Australia and America. So you’ve got people earning really high amounts on one end and people earning very low amounts on the other, and so you need to justify that in some way. And so, yes, that probably means that organisations have become more greedy.”

What does Australia’s gender pay gap look like in 2021?

A recent report, titled Bridging the Gap? An analysis of the gender pay gap report in six countries, outlines the stark reality of Australia’s progress in terms of addressing the gender pay gap, or lack thereof.

Based on 11 indicators, such as best-practice reporting, penalties and accountability – and compared against France, South Africa, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom – Australia ranked at the bottom of the pack, alongside the UK, in terms of pay equality.

Australia is good in terms of collecting data and offering industry reports, says Baird, but there’s a lot of secrecy in terms of pay transparency, as well as a lack of accountability for inaction.

“If you’re found not to have done a gender pay gap audit… there’s no sanction on that. There used to be a time when [non-compliant businesses] were named in Parliament. I think the whole compliance and accountability has softened. [The government] has lent towards the notion that businesses will correct themselves.”

The thing is, Australia used to be world-leading in terms of taking action to address gender inequality at work. We introduced legislation for equal pay in the 1960s and 70s. Gender equality reporting was mandated in the 80s. And, in 2012, the Gender Equality Act required employers to report to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency regarding how many women they recruited and promoted, and what they were paid, amongst other metrics. This data was only shared in aggregate form.

We’re educating and training women at rapid rates, but that’s not translating to increased workforce participation rates. Australia ranks consistently well for women’s education on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index, but has been declining rapidly in female economic participation and opportunity (from 17th place, globally, in 2014 to 70th in 2021).

After a long string of wins, we’ve hit a wall. And COVID-19 hasn’t made things any easier, with the pay gap now sitting at 14.2 per cent, which means women earn, on average, $261.50 less than their male counterparts each week.

The Bridging the Gap report’s authors go on to say that, in 2021, the average female employee needs to work 61 more days each year to make as much money as the average male.

“That’s an aggregate figure and it’s good for publicising the gender pay gap, but the reality is that our labour market is very strongly segregated by industries,” says Baird. “If we look at childcare, for example, the gender pay gap isn’t that [large], but if you look at finance, it could be [larger than a 61-day gap].”

Will ‘downshifting’ make a difference?

One of the legacies of COVID-19 is that many employees have re-evaluated how much of themselves they’re willing to give to their employer. So there could be an employee-led movement towards working less hours. There are even rumblings at a government level of a four-day work week.

So perhaps we shouldn’t be figuring out how to get more women into greedy work, but rather making work less greedy in general.

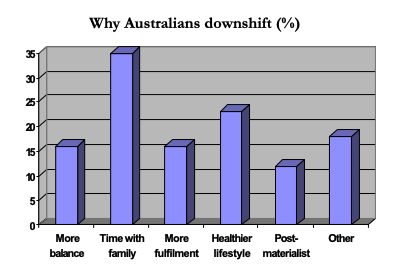

An interesting trend that’s gaining momentum, which could influence this, is ‘downshifting’ – that is, employees choosing to take less pay and reduce their hours in order to give more attention to their personal lives.

Downshifters tend to value time over money and are driven by a desire for a simpler life. The concept is nothing new; researchers have been studying this phenomenon since the early 2000s, but some people are suggesting it could gain momentum post-COVID.

Baird says she can see downshifting gaining traction, but warns that it might exacerbate the issue. It could mean that employers are more likely to hire people who are “willing to put in the extra hours”.

“These people might be better off which could mean we could see a widening of the gender gap.”

In saying this, she believes the pandemic could be helpful to women in other ways. Now that remote meetings have been normalised, we may see less need for international and regional travel, which used to be part and parcel of these high-flying professionals roles.

“Do we actually need people working so many hours?” – Marian Baird AO, Professor of Gender and Employment Relations, University of Sydney.

“[This] opens up opportunities for women to take up those roles.”

Working from home could also moderate some of the greediness of work, she adds. People might still do long hours, but if they’re doing some of it from home, they might be less likely to feel the impacts because of the time gained due to the lack of a commute.

How else can we make a difference?

One thing employers can do to equalise their pay rates across all genders is to make people’s pay transparent, says Baird.

“Then you start to remove that asymmetry of information. That’s the information people use when they’re doing their individual pay bargaining.

“The other way an organisation can limit its wage dispersion is to stick to the enterprise agreements or awards, but a lot of places pay above that now,” she says.

“Another thing we’ve found is that unless you have supportive policies around parental leave, childcare and flexible work, in that order, women will reduce the number of children they have. That’s them internalising the greedy organisation. There’s an inability to reconcile the demands of work with the requirements of becoming a parent.

“A lot of people still want a two-child family, but our research showed that we’re moving towards a one-child family.”

Interestingly, her research also showed a similar sentiment from working fathers.

To her earlier point about the government expecting businesses to take the lead, Baird suggests setting KPIs or goals that you plan to reach within a year.

“Don’t make it a long timeframe, otherwise you’ll never get there.”

The authors of the pay report suggest some other changes.

In an article for The Conversation, they say: “In the short term, we need to make our current legislation work harder to incentivise employers to reduce their gender pay gap. The upside is that accountability and transparency can be improved with minimal change.”

They say this can be done in three ways:

- Publish individual organisation’s pay gaps, rather than just the aggregate data that’s published now. The authors say this change would only require minimal legislative changes for potential maximum gains (i.e. public pressure to improve).

- The Minister for Women, Marise Payne, currently has the authority to set minimum standards for business. The current standards are satisfied simply with the presence of a gender equality policy. This needs to be tied to an action, they argue.

- Introduce consequences for inaction. While the current consequences include potentially not being eligible for government contracts or financial assistance, an audit found that 31 non-compliant businesses were still granted government funding. The consequences need to be stronger and more consistent.

In terms of addressing the greedy work phenomenon, Baird says, “Do we actually need people working so many hours?” Greedy work might simply be a resourcing problem.

“Let’s do the maths. If we all do five hours of extra work each week, and there are ten of us in a team, that’s 50 hours. That’s at least one other person’s job. So going back to [the rise of] lean organisations, something employers could look at, or should look at, is employing more people.”

Address the gender pay gap and workplace inequality by introducing policies designed to support working women. AHRI’s short course on developing and implementing

HR policies is a great place to start. Sign up today.

While we may be working longer hours, I’m not entirely sure it’s unpaid. In the survey referred to, the highest incidence of ‘unpaid’ overtime is amongst mangers and professionals, who are typically paid salaries, inclusive of overtime. I’d suggest the survey question (at Appendix A in the hyperlinked report) needs review.

Why would a business employ an extra person when they can get away with fewer people making up the numbers? Plus, the business may not be able to afford additional staff without making it unprofitable, or because as a government department, that is the limit of their funding (yes, government departments can be greedy workplaces as well !)

I’m not justifying poor business behaviour, just pointing out facts. From the employees perspective, when we keep propping up the system (often through our own pride in getting the job done) then nothing will change.