Women are usually the ones breaking through workplace barriers, but this form of discrimination actually disadvantages men.

You’re a pregnant woman and you’ve just shared the good news with your colleagues – everyone is overjoyed. One of the first questions asked of you – after ‘do you know the sex?’ – is how much time you’re planning on taking off.

You say you’re thinking of taking at least six months, and perhaps coming back part time for a while. The manager nods her head because you’re doing something expected.

Now imagine the same scenario, but this time you’re the dad and it’s your partner who’s pregnant. When you make the announcement at work congratulations are issued, shoulders patted and hey, there might even be a few hugs thrown in for good measure. But it’s likely that the conversations will end there.

When the baby arrives, there’ll be more hugs and congratulations. But once the fanfare is over, it’s expected that everything will return to business as usual.

Obviously each workplace is different, but this is a standard experience for working mothers and fathers. It’s true that these days many men (and women, for that matter) are demanding more options from their employers. But there is a problem. Even when these options are afforded to working dads, there are barriers in place that restrict uptake.

Is ‘flexism’ present in your workplace?

In the latest Quarterly Essay, Men at Work, political journalist Annabel Crabb delves into research that looks into the disparities between men and women when it comes to flexible work and parental leave.

To set the scene, let’s start with this fact. Men are twice as likely to be denied flexible work than women, according to a 2016 study from Bain and Company. This kind of discrimination has been given the name ‘flexism’.

Crabb puts this data into context with a real life example. Brothers Craig and Cameron Zammit both worked as painters for Liverpool Hospital in Sydney. They’d spent eight years starting and finishing early in order to pick their kids up from school. But with new management came a change of policy. All staff had to now work until 3:30pm, meaning the Zammits would have to fork out to pay for childcare as their wives were also unable to pick up the children.

The case was taken to the NSW Industrial Relations Commission. After a four-day hearing, the brothers were denied flexible hours. In her essay, Crabb wonders if the results would have been different had the Zammits been mothers.

There is a growing feeling that flexism is preventing men from participating in household chores and childcare.

And this isn’t just a matter of equality. Having more of a role in the life of their children has been linked to an increase in fathers’ quality of life, including lower mortality, lower risk of alcohol related care and/or death and a reduction in household conflicts.

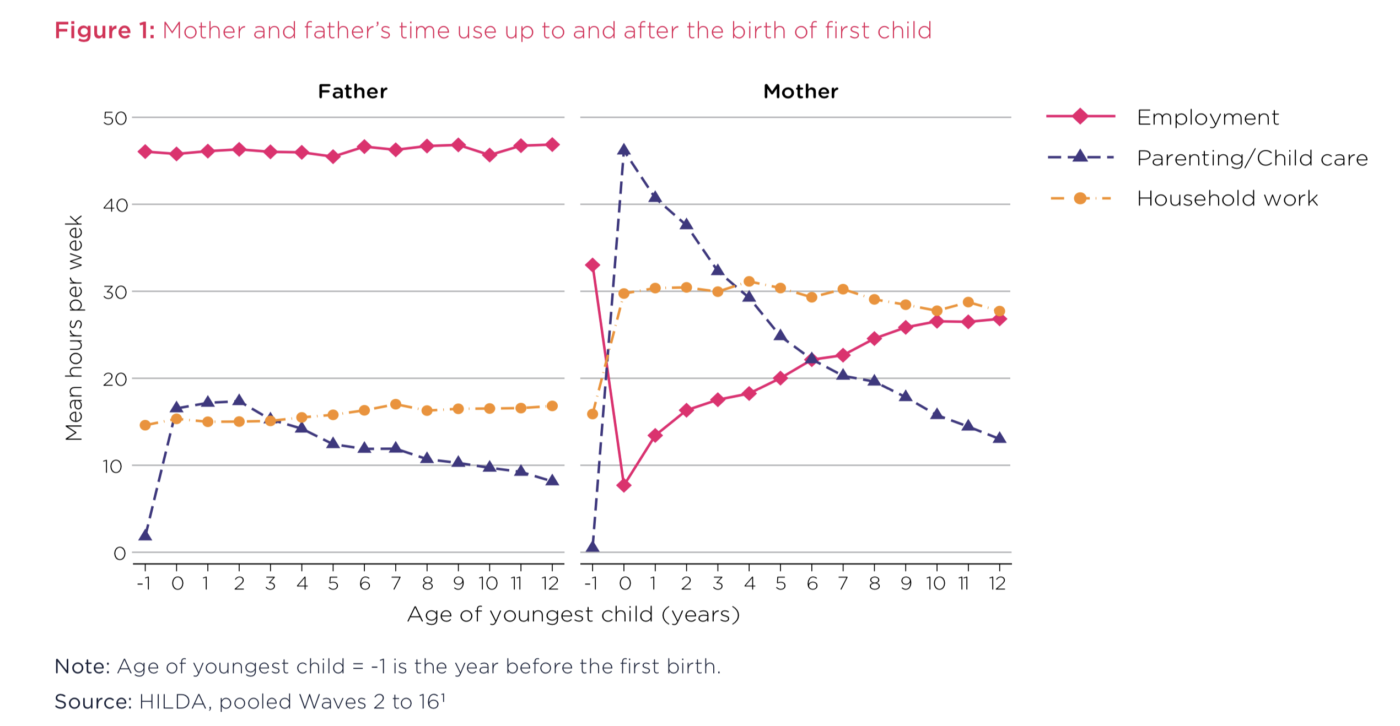

The current disparity between the genders when it comes to both childcare and household work is staggering. In case you missed this gobsmacking graph from our previous coverage of parental leave, here it is again. It’s the only graph that Crabb includes in her essay and it really is worth a thousand words.

Social roadblocks

Parental leave disadvantages both men and women, but in almost completely opposite ways. As Crabb writes, “While motherhood tends to jam a stick in the spokes of a woman’s marketability in the workplace, fatherhood is consistent with greater employability, greater perceived reliability and increased likelihood of promotion.”

Basically, working dads are seen as the breadwinners and are financially rewarded by employers (this is known as the fatherhood bonus). Where the deal sours for dads is when they go against the grain.

Crabb points to a 2013 Canadian study which showed mistreatreatment is worse for those who act against the expectations of their gender – so fathers who take on primary carer roles and women who choose not to have children. The former were considered soft and the latter cold or indifferent.

After the birth of a child, fathers face a chutes and ladders dilemma. They’re in line for more money and prestige, but should they chose to defy the unspoken rules imposed by their gender, they slip down to the bottom of the pack. Crabb calls this the ‘hero-to-zero’ complex.

“This is where the Stay-at-Home Dad is treated as though he has ceased to exist, or has chosen a way of life of no significance whatsoever. Typically, this treatment comes from former workmates who stop inviting him to things and, when they do run into him, say awkward things like ‘Still being Mister Mum, then?’ or ‘So when are you coming back to work?’”

What role do workplaces play in changing this?

You can hear more from Annabel Crabb at AHRI’s International Women’s Day event in March 2020. Register here.

The gold standard

Phil Robinson’s wife was essentially able to keep her job because his employer is serious about supporting working fathers.

As a director in Deloitte’s Financial Advisory Restructuring team, Robinson is entitled to 18 weeks of paid parental leave. This can be taken as a lump sum, as 18 weeks at full pay or as 36 weeks at half pay (including superannuation payments up to 34 weeks).

“Taking parental leave has enabled my wife to retain her Registered Nursing qualifications (which include minimum work requirements for maintaining registration) and keep her engaged in a career she loves,” says Robinson.

Upon returning to work, parents can utilise Deloitte’s ReConnect Program, facilitated in partnership with Parents@Work, to receive coaching and educational resources to ensure the transition back into work is as smooth as possible.

In a bid to remove the misconception that parental leave is a female responsibility, Deloitte re-launched this policy in March this year with a push to ‘share the care’ between mothers and fathers by removing the primary and secondary carer labels in its policy.

The policy is not just a once-off. Robinson has taken advantage of it three times for each of his three kids, and he’s considering a variation of this leave for his soon to arrive fourth child.

“Spending time with my children as they grow up means I get to see the little changes that occur in their lives each day. You see that so much more clearly when you spend a significant period looking after them. I’ve also seen a change in their behaviour. They used to run to Mum for a cuddle when they fell over, but now they come to me as well when they want comfort. We are both seen as providing that role,” says Robinson.

Having an impressive HR policy around parental leave for men is great, but that’s often not enough to quash men’s fears that taking time off will hurt their careers.

Speaking to HRM, Deloitte’s national lead partner, inclusion, diversity and wellbeing, Margaret Dreyer, talked about the layer of social permission in their policy. Much like any organisation-wide cultural shift, it has to come from the top.

“In September 2015 our former CEO, Cindy Hook, personally encouraged men at Deloitte to take extended parental leave through our ‘town hall’ forums and by engaging with new dads to encourage them to take parental leave. Our current CEO Richard Deutsch has continued to champion this cause and build on it, by endorsing a major refresh of our parental leave policy to further challenge societal norms on caring responsibilities,” says Dreyer.

“To encourage more dads to take leave and bring our new policy to life, we created the Deloitte Dads photo exhibition: professional photos of dads from Deloitte spending time with their children. Each photo is accompanied by comments from the dad on the value of parental leave. This exhibition toured the country, being shown in the reception areas of Deloitte offices, to encourage conversations around the acceptance of dads taking parental leave.”

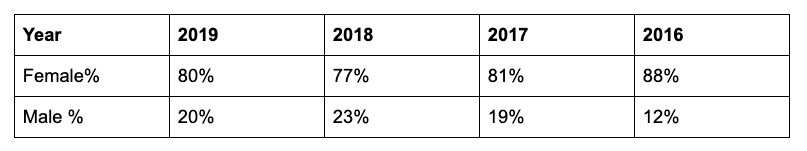

You can see the relative uptake of parental leave, split by gender, in the table below.

It’s encouraging that organisations like Deloitte take a progressive approach to parental leave. But policies like this highlight another issue about flexible work for men – it’s not always a gender issue, sometimes it’s an industry issue.

Blue-collar dads

Bill works 60 hour weeks as a bricklayer. He and his wife are also expecting their fourth child, but Bill has never had the opportunity to take more than the government allocated two weeks of secondary care at minimum wage. His employer simply doesn’t have the resources to offer paid leave and, as it’s a male dominated workplace, it hasn’t really been forced to confront the issue.

It’s crazy to think that the factor determining if a father forms a special bond with his child during its early development stages is whether or not his employer has a policy in place.

Crabb touches on this topic too, writing that while flexible hours are sometimes available for blue-collar workers, the option to work from home is all but non-existent for many of those working on a construction site, in a delivery truck or in a mine.

“The truth is that equality of opportunity for both flexible work and parental leave is coming quicker for well-paid white-collar workers than it will for other workers,” says Crabb.

She refers to Telstra as an organisation with a strong portion of both blue and white-collar workers that has bridged this divide. It took a similar approach to Deloitte this year, banishing primary and secondary care policies in favour of a blanket parental leave policy for all staff (it has been offering flexible hours for all roles since 2014).

Again, this is fantastic, but again, it’s a policy born from an organisation with very deep pockets. It’s not doing anything to help Bill spend more time with his newborn.

In her essay, Crabb talked to Emma Walsh, CEO of Parents at Work, who said, “We need to make sure that government is in step with the mood. Leaving it to the private-sector has the effect of improving things only for a certain group.”

But without government legislation to drive a wider change, that’s exactly where the responsibility currently lies. It will be interesting to see if growing demands from all parents – both those concerned with flexism as well as gender equality – will change things.

A great article that is supported with solid evidence.

My neighbour had her baby mid 2019, she took the first 6 months maternity leave now her husband has taken 6 months LWOP so she can return to her career – such a lovely and uncommon gesture from her husband

My neighbour will have his baby mid 2020, he’ll take the first 6 months LWOP and his wife the next 6 months maternity leave so he can return to his career – such a lovely and uncommon gesture from his wife.

[…] both Deloitte and Medibank noticed an uptake in men utilising parental leave when flexible options were introduced. Medibank saw a 25 per cent […]

[…] matters because we know that if more fathers are involved in parental leave, that is a boost for women’s full-time labour force participation. That’s going to help […]