Even though we know unnecessary meetings are time-suckers, concepts such as the egocentric bias and pluralistic ignorance often prevent us from hitting ‘decline’.

Unnecessary meetings are the bane of most knowledge workers’ existence, closely followed by an overflowing inbox and the use of complicated jargon.

A day full of meetings is universally understood as a day that could have been better spent, yet when it comes to clicking ‘decline’, or deciding not to schedule a meeting in the first place, we struggle.

How can we overcome this decades-long issue?

What’s meeting overload actually costing us?

Before we dive into the psychology behind why we’re so addicted to meetings, it’s worth assessing what we’re losing when we add more and more names to that meeting invite list.

Research from Otter.ai, an online transcribing platform, found that 15 per cent of an organisation’s time is spent on meetings and that middle managers spend 35 per cent of their time in a meeting.

You can read hundreds of articles and research papers on the productivity drain caused by excessive meetings, but it’s not until you cost up your own financial losses that it really hits you.

“In general, we aren’t very good at calculating the opportunity costs of our time,” says Ashley Whillans, Associate Professor at Harvard Business School, who originally wrote about the psychology behind meeting overload for Harvard Business Review, alongside co-authors Dave Feldman, Founding CEO, and Damian Wisniekski, Founding COO, of Miter.

“We often fail to realise… the value of the time wasted in unnecessary meetings. By calculating the cost of meetings to the company, we can begin to realise how expensive meetings really are and hopefully schedule fewer of them.”

How could we possibly put a number to that, you ask? This handy meeting cost calculator can do all of the heavy lifting for you.

Take a moment to look in your diary and find the last meeting you went to that had more than two attendees. Input the number of people present, estimate the salary range of each person and then input the length of the meeting. The calculator will then generate how much money that meeting cost the company (my last meeting cost approximately $1,218 for 30 minutes).

Now think about the purpose of that meeting. Did you achieve what you wanted? Was everyone needed there? Was there an outcome that will help to further your business somehow?

If the answer is ‘yes’ then that was money well spent. However, this often isn’t the case. The majority of meetings, according to research, prevent employees from completing work, are unproductive and inefficient, and interrupt people’s deep thinking time.

“For the most part, managers see employees wanting to protect their calendars as a signal of commitment and motivation to produce higher quality work.” – Ashley Whillans, Assistant Professor, Harvard Business School

And research from Atlassian found that people wasted 31 hours per month in unproductive meetings and considered half of all their meetings as being time-wasters.

All of this isn’t to say we need to stop having meetings all together. When done properly, they function as vital knowledge sharing and decision-making forums, and in hybrid environments it’s important that we’re facilitating moments of connection between teams. We just need to be aware of the various factors that are preventing us from being more strategic with our meetings.

Egocentric bias gets in the way

Egocentric bias describes the tendency to zero in on your own perspectives, meaning you might struggle to put yourself in someone else’s shoes.

This can manifest in a few different ways. For example, an individual might worry that people will notice they’re wearing the same outfit as they did earlier in the week, when most people wouldn’t notice (or care).

In a workplace setting, leaders might succumb to this bias when scheduling meetings. They’ll find a small gap in their own calendar and assume everyone else is also free to meet, or they’ll deem a topic important enough to interrupt people’s workflow, assuming other people will feel the same.

In their HBR piece, Whillans, Feldman and Wisniekski write that egocentric bias can sometimes lead to ‘selfish urgency’.

“That is, leaders will schedule meetings whenever convenient for them, without necessarily considering their teams’ needs or schedules. Sometimes leaders even knowingly schedule meetings when their team has conflicts, forcing everyone to shift their calendars around to accommodate,” they write.

Whillans says this phenomenon is rarely intentionally harmful on the leader’s end.

“Leaders are very busy and trying to juggle many tasks and priorities simultaneously. We know from the academic literature that being busy can make us focus on what is in front of us, without seeing the bigger picture – which is referred to as myopic thinking,” she tells HRM.

“By scheduling at a time that is convenient for them but not necessarily good for their teams, leaders are engaging in myopic thinking. To avoid this, [they] should stop and think about the impact of any one meeting on their team’s productivity and happiness.

“Will another meeting move the needle? If yes, go for it. If not, consider whether an entire team meeting is needed or whether your teams’ time might be better spent elsewhere.”

If leaders don’t come to the realisation that not all meetings are essential, it can be really challenging for their teams to decline yet another ‘quick’ catch up from someone in a position of authority or influence; they don’t want to seem rude.

“I would suggest that employees come together to provide input to leadership,” says Whillans.

“Employees could focus the conversation on how managers could help them be more efficient and productive, and feel less stressed, such as by having fewer meetings.

“My research suggests that employees fears are often unfounded. They worry about the signal that asking for more time will send to their managers, but for the most part, managers see employees wanting to protect their calendars as a signal of commitment and motivation to produce higher quality work.”

Meetings make us feel important

As HRM has covered before, many of us have a tendency to glorify being busy. What better way to do that than with a day packed to the brim with meetings?

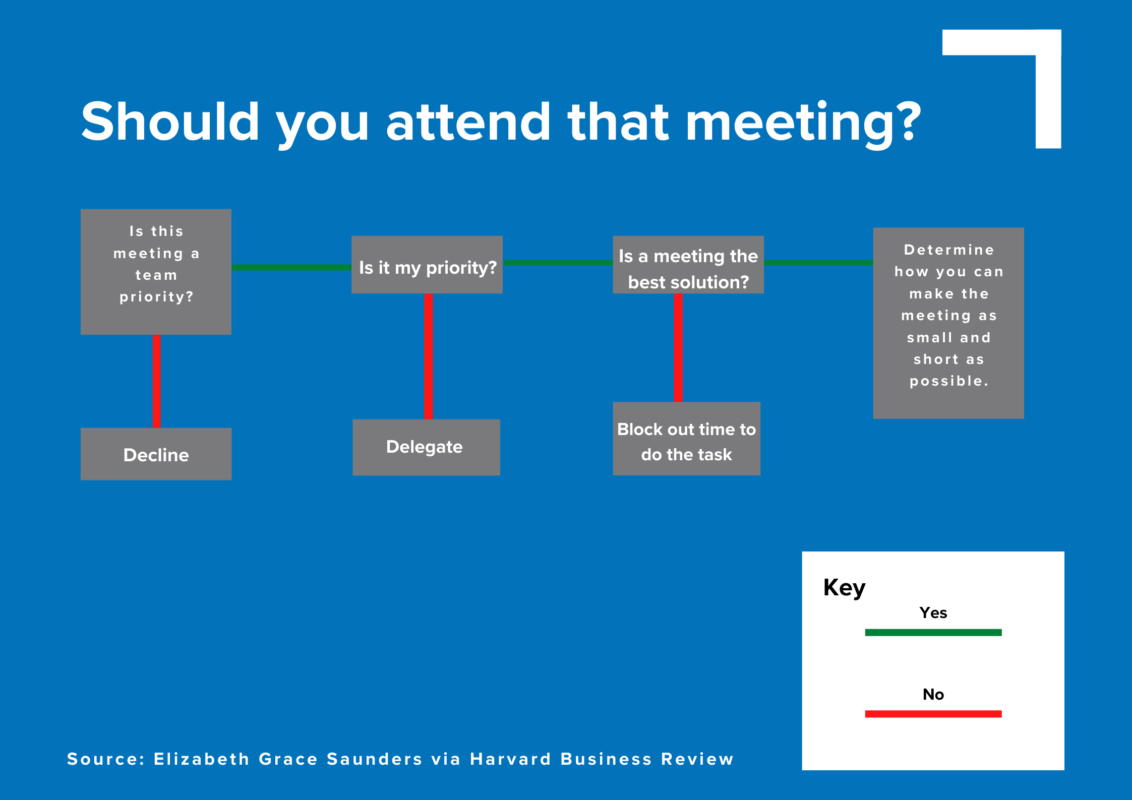

In a separate HBR article, time management coach Elizabeth Grace Saunders poses the question, ‘Do you measure your value by how many meetings you’ve been invited to?’

It’s worth really considering your answer.

Even if you don’t realise it, if you’re someone who often talks to other people about being in back-to-backs all day, or if your first instinct when seeing a meeting-free day in your calendar is to start scheduling in calls, the answer might be ‘yes’.

This isn’t to say you’re an unproductive worker – meetings are part and parcel of some people’s jobs, afterall – but it could mean you’re suffering from a bout of productivity guilt.

We’re operating in work environments that demand more of our time, efforts and resources than ever before. That can be overwhelming and one way to feel as if we’re making progress is to schedule a meeting, even if we’re just meeting for the sake of meeting.

We know we need to be more discerning about how meetings are utilised, but how can we do that?

For attendees, Saunders suggests asking a question like, ‘Would this meeting be cancelled if I was off sick?’ If not, and you can’t attend the meeting for a different reason, think about other ways you can contribute, such as adding thoughts to the meeting notes after the fact.

Saunders has developed a helpful decision-making tree that you could follow.

We feel we need to be seen

Meetings are often treated as a place to show face. Employees might think if the boss sees them pop up on the screen, they’ll be deemed as an engaged, committed and hard-working employee for that day. Of course, this isn’t always reflective of reality.

A 2021 study of Microsoft employees in the US found that multitasking during meetings has become common practice. The research found that during meetings employees would interact with their emails 30 per cent of the time and attend to work files 25 per cent of the time.

Atlassian’s research supports these findings, stating 91 per cent of people have daydreamed during a meeting and, surprisingly, 39 per cent have actually fallen asleep.

While this is obviously much easier in a virtual environment where you can turn your camera off, let’s not forget that it happens in person too – that’s why laptops around the meeting table are generally considered a no-no.

You can assume these people feel there’s little value in their involvement in the meeting, so why even attend?

Whillans, Wisniewski and Feldman suggest it’s because most of us have what they call “meeting FOMO”; we don’t really want to attend the meeting, but we don’t want to necessarily miss out on it either.

We fear non-attendance could look like we don’t care about our jobs, or worry it could mean we’ll get left behind, they suggest.

“Deeply ingrained norms around what it means to be an ‘ideal worker’ lead us to equate presence with productivity, and these assumptions are bolstered when bosses use facetime as a proxy for commitment, or when they fail to represent absent employees’ opinions in meetings,” they write.

But this isn’t really providing us with any useful data. Instead, Whillans says “we should use quality of work as opposed to constant responsivity as a proxy for commitment”.

Another interesting point the trio raise is that many people also have a tendency to become invite-happy. Not only do we feel we have to attend all the meetings we’re invited to, we feel pressure to invite more people than are needed, for fear of hurting someone’s feelings by leaving them out.

To combat this, they suggest:

-

- Reframing your thinking. Don’t think of leaving someone off a meeting invite as a bad thing; you’re being respectful of their time.

- Utilise the ‘optional’ functionality on most meeting invites. This means people can assess if they really have the time to attend on the day.

- Allow people to share their perspective via email rather than having to attend the meeting.

- Weigh up the costs involved. Before sending out that invitation, try using a tool like the calculator above to determine if the benefits will outweigh the costs.

We think other people actually enjoy the meetings

When you’re sitting in your fourth Zoom call for the day and you see all your colleagues seemingly engaged in the conversation and nodding along, it can be easy to think you’re the odd one out for feeling frustrated by another meeting eating into your work time.

Whillans, Feldman and Wisniewski refer to this phenomenon as ‘pluralistic ignorance’, “a phenomenon whereby even though we’re all experiencing the same thing, we assume that other people don’t feel the same way about it as we do,” they write.

When this happens, we’re more likely to let the same behaviours continue – in this instance, scheduling, attending and advocating for more meetings.

But this practice isn’t exclusive to meeting overload.

In 2014, when flexible work arrangements were only afforded to a small minority, sociologist Christin Munsch of Stanford University’s Clayman Institute found that pluralistic ignorance held a lot of people back from utilising flexible working arrangements.

While most people actually viewed flexible work favourably, they assumed others viewed it negatively, meaning the uptake was low and the overall perception of flexible work was negative.

This strays into confirmation bias territory, which is when we go against our gut feeling in order to conform with the view of the majority – a concept popularised in the 1950s by Solomon Asch with his famous ‘Asch experiment’ (see video below).

A phenomenon like this could prevent people from engaging in all sorts of healthy workplace habits, like leaving on time, taking annual or sick leave or taking up parental leave as a working father.

The lesson? HR professionals and leaders play a critical role in helping to shape the narrative of certain workplace practices to help people put practical boundaries in place.

“Teams should have explicit conversations about large meetings,” says Whillans. “If you see a large meeting that is recurring, have a team conversation about it where you ask everyone to report what they see as the value of that meeting.

“Very likely you will realise you all think that meeting isn’t useful, but didn’t want to say anything because no one else had mentioned [it]. Critical conversations are a good way of breaking silence and pluralistic ignorance.”

Quick suggestions to combat meeting overload

So now that we know some of the reasons we’re addicted to attending and scheduling meetings, what are some small changes we can implement? Whillans shares some ideas:

-

- Create ‘time affluence‘ for your team – that means giving people back time in their day. Whillans says it’s one of the top three predictors of engagement for employees right now. An easy way to do this is to assess your upcoming meetings for the week and cancel any that you don’t think will add value.

- Schedule meeting-free time in everyone’s diaries (say 12-2pm every day) or introduce a rule that you won’t ever schedule meetings after 5pm.

- Set up ‘team norms’ around employees’ time at work, so people are accountable for how they’re spending their breaks or deep work time effectively.

Finally, here are some other suggestions you could try:

-

- Nominate one person to attend a meeting and represent the views of their team (which can be collated via email beforehand).

- Don’t schedule meetings for things that could be communicated via an email, such as FYI items and progress updates. Meetings should be reserved for discussions and decisions.

- Create shared and agreed upon language for declining meetings across your company. This article from Meister includes some good templates for various circumstances.

- Conduct regular ‘meeting purges’. Every quarter you could look at all the recurring meetings in your team’s calendars and axe those that are no longer serving you.

- Consolidate all your meetings into one or two days. This will help people to plan out their weeks better. It could also work well for a hybrid environment when people are determining which days they should be in the office.

These might feel like relatively minor changes, but that last point alone has proven to pay businesses back in spades.

In a recent survey from MIT Sloan, 76 companies that had introduced meeting-free days were studied. Nearly half were able to reduce all meetings by 40 per cent after doing this, and many saw increases in autonomy, communication, engagement and productivity as a result. So why not try something similar in your workplace?

Next step: set up a meeting to discuss which meetings to cut out…

This article was inspired by a Harvard Business Review article originally published on 12 November 2021. Thanks to Ashley Whillans, Dave Feldman and Damian Wisniewski for starting this conversation with their original article, which you can read here.

Got some great tips to cut out unnecessary meetings? You can share your thoughts on topics like this with your HR peers over at the AHRI LinkedIn Lounge. This is exclusive to AHRI members.