PwC and KPMG are leading the way in transparent corporate accountability. Here’s why you should follow in their footsteps

In a radically transparent move, two major professional services firms, KPMG and PwC, have released reports detailing the number of recent workplace complaints both firms have received, setting an impressive corporate accountability benchmark in the hope that others will follow suit.

According to its inaugural Impact Report, KPMG employees reported 27 complaints, including three allegations of sexual harassment, that were fully or partially substantiated.

Meanwhile, PwC’s Transparency FY21 report reveals 13 bullying, harassment, sexual harassment and serious misconduct complaints that were reviewed by its Employee Relations Panel.

These details of the workplace complaints only scratch at the service of what these corporate accountability reports included. Both firms took things a step further, sharing details of gender disparities, cultural diversity in leadership, the firms’ climate impacts and how much tax both companies pay.

Neither organisation is publicly listed, meaning they weren’t under legal obligation to release this data. So why do it?

“We’re doing this voluntarily because we know if we don’t people will still ask the question, ‘How do we know what’s going on at PwC?” says Catherine Walsh, PwC’s Head of People and Culture.

“We can’t ask our people to trust us if we’re not going to give them the information they need to build that trust.”

According to a report from Workplace Express [gated], KPMG addressed its substantiated complaints, with consequences including warnings, financial penalties and terminations. In response, the firm has also indicated that it would rejigg its sexual harassment policy to be victim-centric, a move that Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins has previously called upon all employers to do.

Corporate responsibility

Both reports were inspired by the World Economic Forum’s Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics, which encourages organisations to measure their financial reports against environmental, social and governance indicators.

For Walsh, it was a chance for PwC to show that it stands by the values it holds its clients and employees to.

“We’ve taken a really strong position around environmental sustainability and governance,” she says. “If we’re going to be talking to clients about that, we obviously need to make sure we’re holding ourselves to the same standard.”

This sentiment is echoed at KPMG, where its National Managing Partner for People and Inclusion, Dorothy Hisgrove, says these reports show the organisation is walking the talk.

“We believe that transparency helps our clients, our people and partners, and other stakeholders better understand our values,” says Hisgrove.

Both Hisgrove and Walsh say the reports have been great conversation starters in their workplaces, prompting employees to ask questions and hold the organisation accountable for its actions.

“We’re showing, ‘Here’s where we are, here’s where we want to be,’ and we want our people to be involved with that. We want to continue having conversations about the things in this report over the next 12 months,” says Walsh.

These reports also act as benchmarks to share year-on-year progression in areas that matter to the various stakeholders and, since both firms have essentially shouted their intentions from the rooftop, there’s a healthy amount of public pressure to make good on these promises.

“We can’t ask our people to trust us if we’re not going to give them the information they need to build that trust.” – Catherine Walsh, Head of People and Culture, PwC

Creating a transparent workplace

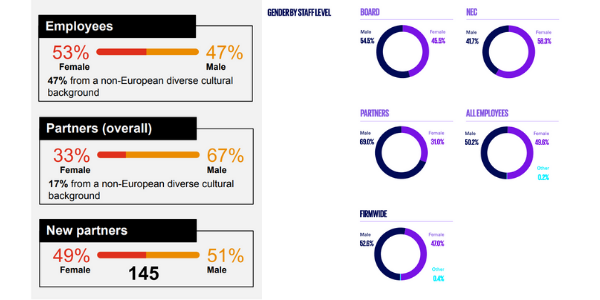

Both reports have a ‘people’ section which breaks down how diverse each workplace is in terms of gender and age groups. Both organisations revealed they have a pretty even split between male and female employees. However, both still have male-dominated C-suites. See graphs below.

Walsh acknowledges that the report airs out some not-so-positive truths, but she believes it’s important for the organisation to acknowledge its shortcomings.

“This is us demonstrating that we’re not perfect, there’s always room to improve, but we’re prepared to do that work,” she says.

The details of the various workplace complaints regarding poor behaviour also sit in this ‘people’ section of the report, which Hisgrove identifies as one of the most necessary inclusions in the report.

“I don’t think you can share an Impact Report without being open about where you’ve had to make hard decisions,” she says.

“Our people, clients and stakeholders have been really pleased by the openness that we have shown, that we treat workplace complaints with the gravity they deserve, and that we have taken action. ”

This report is just the start, says Hisgrove. Future reports may reveal more information about KPMG’s workforce and outline room for improvement.

“We see our first Impact Report as the start of a conversation that we will build on, reflect upon, and continue to add to on a range of topics and metrics,” says Hisgrove.

“This is us demonstrating that we’re not perfect, there’s always room to improve, but we’re prepared to do that work.” – Catherine Walsh, Head of People and Culture, PwC

Lean into the discomfort

If these reports are just the beginning, should other employers be following suit?

According to Hisgrove, absolutely. The next generation of employees are demanding more from their employers, so leaders need to be prepared to show them what they stand for.

“There is much to be gained from engaging openly and transparently, even when this creates discomfort,” says Hisgrove.

“Such honesty, I believe, is the only way to build the trust necessary to move forward together with confidence in a world that is increasingly complex and challenging.”

Walsh agrees, saying: “You need to be fearless.”

“It can sometimes feel uncomfortable and you can feel a bit exposed. But it drives a really great conversation and it drives us and the team to be better.”

Reports like these mark a new step in how organisations approach issues such as corporate social responsibility and corporate accountability.

Organisations that don’t acknowledge that employees, prospective and current, demand more transparency and action are ignoring the writing on the wall.

“Generation Z now make up a huge proportion of the workforce and this generation expects, [and often] demands, more from the companies they choose to work for,” says Hisgrove.

“If we are to continue to attract the best talent, we have no choice but to do more in this space.”

Walsh adds: “Any organisation that thinks that it can exist without [listening to] the scrutiny of its workforce doesn’t really see what’s happening in society more generally.”

It will be interesting to see how reports of this nature evolve over time, and if more employers join the fray. The World Economics Forum hopes corporate accountability at this level will lead to “more prosperous, fulfilled societies and a more sustainable relationship with our planet”.

In the meantime Walsh and Hisgrove are keen to dive into the work of putting their words into action.

“This is a great tool for me to now work with the business and our leaders to drive those things that matter most to our people,” says Walsh. ”You just need to be fearless and dive in.”

What do you think about sharing details such as these with the public? Let us know in the comment section.

Publishing workplace complaints is a bold step, but before that you need a robust investigation process. If this is an area you could improve on, AHRI has a short course that could help.

What must I do with sexual harassment reports and bullying reports if I have nothing to do with them?

What is the level of detail that is divulged? Investigations and outcomes are kept confidential – are these reports simply outlining the types and numbers of complaints/issues or does the transparency extend to a “name and shame” level?