The push-pull leadership style is a subtle balancing act, but it’s crucial to get it right if you want to push employees out of their comfort zone.

Remote work, the pandemic and a general rise in rates of burnout and poor mental health have put leadership styles into the spotlight of late.

There have been calls for leaders to adopt empathetic and empowering leadership styles (including from HRM), as well as a new-found focus on offering employees more autonomy.

This is likely to set a new standard for the ways in which leaders are expected to behave, and could mark the beginning of the end for the authoritative leadership style that has reigned supreme for so long.

However, experts suggest that we shouldn’t ditch all elements of traditional leadership as we move towards a more empowering model.

In fact, Joseph Folkman and Jack Zenger, founders of leadership development consultancy Zenger Folkman, have conducted research which suggests that a highly effective leadership style combines both an empowering ‘pull’ approach with an encouraging ‘push’.

Push versus pull

If you think of a leader who is directive, prescriptive, authoritative and holds people to account, that’s generally someone who is adopting a ‘push’ method.

Leaders who are inclined to pull, however, tend to favour empowering models, such as collaborating with employees on the design, approach and deadlines of a task, or inspiring others to do their best work, rather than telling them to.

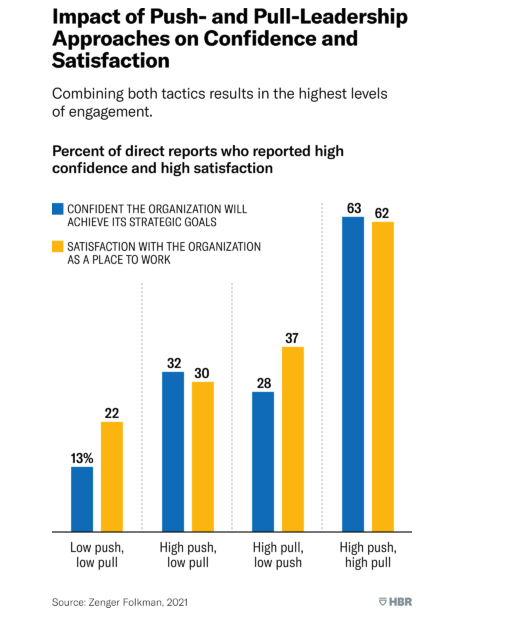

Zenger and Folkman conducted research based on data from over 100,000 leaders’ 360-degree assessments, the results of which were outlined in this Harvard Business Review article.

They found that the majority (76 per cent) of people felt leaders were more effective at the ‘push’ method – which isn’t that surprising. Less than a quarter (22 per cent) were identified as being effective at pulling and only two per cent were thought to be competent at both styles.

Zenger and Folkman’s data revealed that while respondents considered ‘pulling’ to be more important, it was leaders who could seamlessly move between both styles who were ultimately the most effective.

Not only were employees more satisfied working at an organisation where leaders employed a push-pull leadership style, they also felt more confident that the organisation would reach its goals (see chart below).

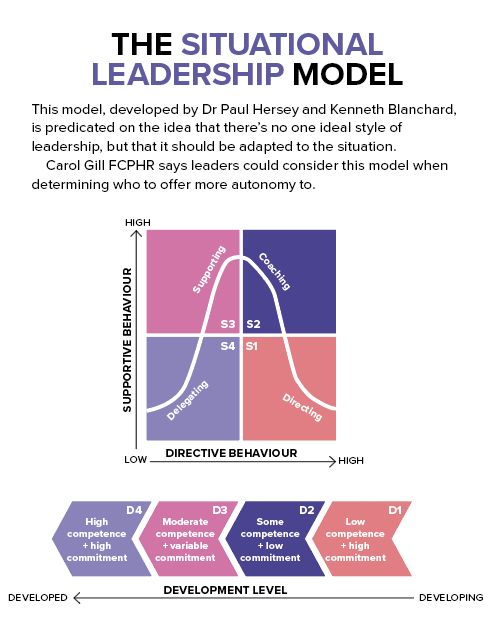

“This is a new interpretation of old material,” says Carol Gill FCPHR, Associate Professor of Organisational Behaviour at Melbourne Business School. “It’s much like situational leadership [see graph below], which is a more commercial version of path-goal theory.

“In situational leadership the suggestion is that leaders have a combination of something similar to the push and pull; they have to be directive at times, and other times they need to show consideration. But the difference with situational leadership is that it also proposes that sometimes you need low levels of both.”

In situational leadership, the approach is dependent on the followers, she says.

“Followers need different things. For example, when they’re new and don’t know what they’re doing, they need more of a push. The argument is that as someone develops, if you get these two things mixed up and you push instead of pull, you can alienate people.”

Being able to change your leadership style based on your circumstance is a “fantastic leadership capability”, says Gill.

“To do that, you need self-awareness. You need to be able to say, ’I know it’s my default to push, but I know this isn’t the moment to push, because my people have reached a particular level. I need to put aside my default and adopt new behaviours, even though I’m stressed.’ When you’re stressed as a leader, you go into a panic zone.”

Push techniques shouldn’t be used from a place of stress on the leader’s end. It needs to be a strategic, thought-out approach.

“You may not know at that moment how someone is going to cope, but if you’ve built up a pull-style relationship before you need to start pushing, you’ll likely have more success.” – Carol Gill FCPHR, Associate Professor, Melbourne Business School

Gill notes that most employees these days want to be pulled.

“The thing about pulling people along is that you develop commitment, whereas if you’re just pushing, it feels more transactional. So if you’re a leader and your back is turned or you’re on leave, that person will stop doing what you want them to do.

“It can lead to passive aggression – which is sometimes worse than them quitting. If someone leaves, there’s only a hole in the short term, but if someone stays… they can do all sorts of sabotage. That could be excluding others, not passing on information, or sabotaging clients or products. I think it’s a little bit of a dangerous strategy, but I do recognise that from time to time you might need to use a push strategy.”

Knowing when and how to push employees

So leaders may need to push in moderation, but how can you tell when a situation calls for a firm approach?

It’s not always an employees’ seniority or experience that would dictate when a push approach may be beneficial, says Gill. It may also be necessary during times of change or disruption.

“As [Zenger and Folkman] suggest in that article, even when very experienced people are faced with new things, they need help to address what’s required to be done because everyone resists change at a level.”

When time is of the essence, leaders may also need to push.

“If something is mission critical, you might [push employees] and then mop up the mess later. You might then say, ‘Sorry I was so directive yesterday, but the client needed this… and so on.”

There are other instances where leaders will need to put their foot down, such as on time-sensitive issues.

“They might then say, ‘I know you’ll probably have some issues around this, but, to be frank, you’ve got to put those aside because we’ve just got to get on with this.’

“Also, if you’re dealing with an individual who is recalcitrant, is an under performer or somebody who’s got a bad attitude towards the organisation and is a bit lazy, those people might need a poke… you’ve just got to be careful that it’s not bullying.”

If you’re in need of some examples of healthy and productive ways to push employees, consider the following points:

- Ask an employee to run a meeting they’d usually be a passive participant in.

- Get someone to work outside of their area of expertise on a challenging task.

- Avoid offering a solution the next time a problem emerges and ask the employee to come to you with their proposed solutions.

- Set ambitious but realistic goals for the employee to meet that take them out of their comfort zone.

- Have them present something to the company.

- Ask them for feedback on how processes/systems could be improved and then task them with coming up with a better approach.

- Place them on a secondment into a role with more responsibility.

- If they’re at an appropriate stage of their career, consider having them mentor or coach a junior employee, and make them accountable for elements of that employees’ development.

Going beyond the comfort zone

This may all sound well and good, but perhaps you’re still concerned that leaders will take it too far. In that case, you can share the following advice with them.

Firstly, they should make sure people are aware of their ‘why’.

“Leaders should explain to people why they’re doing something,” says Gill. “They might say, ‘I haven’t got time to explain everything to you now, but I might be able to do that later. For now, I need you to just to X,Y and Z.'”

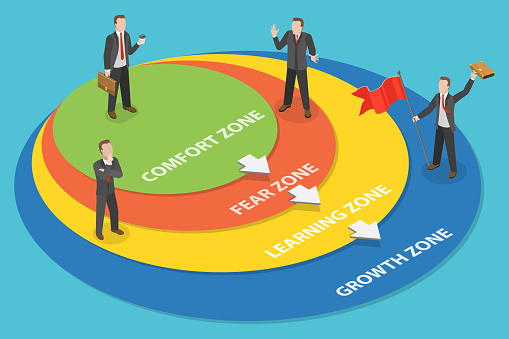

Leaders should also consider people’s comfort zone, growth zone and panic zone, says Gill.

“The argument is that when you’re in the comfort zone, which is the inner circle, you don’t grow; you don’t change. You’re just doing the same thing you’ve always done.”

“But if an organisation introduces a change [or challenge]… you move into the growth zone. And that’s the point of discomfort where you can learn something, but it’s not an imploding zone. You’re not at a point where you think, ‘I’m so stressed. I can’t deal with it’ – which is the panic zone. It comes down to a judgment call from the leader. They need to ask, ‘How far can I push my people?’

“The leader also has to build psychological resources for their people as much as they give direction. In other words, when someone is really stressed – like we were during COVID-19, or maybe today it’s about being short-staffed – it increases the demands on them. And if those demands hang around too long, it results in burnout.”

In these scenarios, Gill suggests leaders employ perspective-making statements to build people’s resilience.

That means using words of encouragement to get through a push period, reinforcing the ‘why’ and how long the push period may go for – e.g. ‘We just need to put our heads down this week and then we’ll be able to take a breather’ – and giving people a view of the bigger picture.

That might look like demonstrating why you’re putting them in a potentially uncomfortable position – e.g. ‘I’m asking you to run this meeting on your own, and without much guidance from me, because it’s really important that you know how to step up if I’m ever absent.’

Gill says the golden rule of pushing employees is to begin with a strong foundation built upon a pull approach.

“You may not know at that moment how someone is going to cope, but if you’ve built up a pull-style relationship before you need to start pushing, you’ll likely have more success.”

If you want to sharpen your leadership skills or go beyond your own comfort zone, AHRI’s short course, Leadership and Management Essentials, is designed to set you or your team up for success. Sign up for the next session on 10 October.

The push-pull-leadership may address the phenomenon of reluctant stayers (according to the PWST of Hom et al., 2012)