The highest-ever recorded levels of change fatigue, a rise in ‘resenteeism’ and misaligned communication about organisational growth could be a recipe for a disengaged and disgruntled workforce. Here’s how you can reverse the impact of organisational ennui.

If you’ve seen a noticeable increase in languishing behaviours from employees of late – they’re less inclined to go above and beyond, they seem disinterested in supporting organisational growth agendas, they’re displaying visible signs of disengagement – then you’re not alone.

Gartner’s latest Global Talent Monitor survey data, relaying sentiments of 6000 employees from April to June 2024, shows that engagement among the workforce continues to flatline, with just 22.8 per cent of the workforce rating themselves as “highly engaged”.

It also shows that Australian employees’ perceptions about how innovative their work environments are reached an all-time low of 14 per cent this quarter, which is a 10 per cent decline from a high of 24.5 per cent in 3Q21.

There are many reasons for this, says Aaron McEwan, Vice President of Research and Advisory at Gartner.

“There’s a lot going on. We’re still in a post-pandemic hangover, there’s a cost-of-living crisis and political turmoil – everything feels like a more intense version of Groundhog Day,” he says.

These external pressures are driving businesses to increase the dial on transforming their operating models at an enterprise level, meaning employees are facing extreme periods of change both in and outside the workplace.

McEwan says this is resulting in a worrying trend.

“We went from the Great Resignation to Quiet Quitting, and now we’re moving into this new buzzword: resenteeism. This is where people are resentful of their employer. They’re not planning on going anywhere, but they’re resentful.

“We know from previous research that there’s this interesting direct correlation between the number of what we call ‘career moments’ – things like getting a new boss, your responsibilities drastically changing or losing a team member through a downsizing exercise – and the likelihood that an employee will engage in misconduct.”

This could be anything from stealing company stationery through to bullying, harassment or industrial sabotage, says McEwan.

“People don’t want to be managers anymore, because you have to carry cognitive dissonance 24/7 to be a leader today.” – Aaron McEwan.

“One of the things we’ve been tracking is that workplace conflict is rising. Sitting underneath this is the fact that people are experiencing the highest level of change fatigue we’ve ever recorded. The danger for organisations is that even if a small percentage of your workforce – which might not show up on an engagement survey – are resentful, they might be slipping into more active forms of misconduct.

“We saw this recently with the CrowdStrike issue. This one software glitch can shut the world down overnight. All it takes is a disgruntled, resentful employee to let a nefarious agent into your systems to wreak havoc. This is a dangerous time for organisations, and I don’t think our current approach to engagement is up for the task.”

We’re missing a critical period of stability

The majority of business leaders McEwan is communicating with at the moment are seeking support to achieve enterprise-wide transformation.

“Human beings aren’t change-resistant. Sometimes they’re change cynical, and often for good reasons.”

He says more workplaces need to ask the critical question: Is our workforce ready for this?

“I don’t just mean, ‘Are they going to be resistant?’, because that’s the usual assumption, but rather, are they in the right place to take on this additional level of change? If you had a piece of machinery that had been running at 5000 revs for the past three and a half years, you’d be a little bit worried about the wear and tear on that. If you were then about to embark on another accelerated period of growth, you’d want to make sure that equipment is up for the task.

“I do think there are probably segments of the workforce that are broken or damaged.”

Instead of trying to shoe-horn a change initiative across all segments of your workforce, he recommends chunking strategies down and starting with change-ready units.

“HR has a huge opportunity to be a stabilising force in the organisation while transformation is occurring. Transformation is going to happen, it has to happen, but it doesn’t have to be this overwhelming tsunami of change which seems to be constantly buffering the workforce.”

HR can create pockets of calm. This sometimes means ensuring close collaboration with ‘transformational leaders’ – i.e. those who tie a large portion of their identity and success to the amount of transformational change they deliver.

“There’s an increased rate of turnover at the executive leadership level. On average, we’re down to about 18 months’ tenure for the average CEO. What does every CEO do when they join a new company? Transformation. This might be a little controversial to say, but maybe it’s time to say, ‘Enough already.’

“If the transformation is needed, and it’s necessary to achieve [desired] growth levels, then absolutely embark on it. But if your workforce is already in a tailspin, and you’re going to send it into another tailspin [with more change], then that should be justified.”

While McEwan notes that it can be challenging to get a CEO to hit pause on their plans, he says there are plenty of “brave CHROs out there” who can champion the readiness and capacity of the workforce to absorb and respond positively to transformation.

Help your organisation manage change and transformation effectively by arming yourself with the key skills required for successful change management with this short course from AHRI.

Employees feel like workplaces don’t need them

While volume of complex change is a key factor driving these feelings of organisational ennui, there are also other factors at play – factors that are within the control of businesses.

“The pandemic was really hard, but it was also a period of intense innovation. We had to work out how to do our jobs differently. There was a brief period where employees were given a really clear sense of what’s needed in a crisis and then were left alone to do it. That resulted in a lot of innovation and creativity.”

Now, the context isn’t as conducive to creative thinking. Return-to-office mandates are a notable part of the issue, says McEwan. We’ve seen local examples of such mandates in the NSW government, but this is also happening on the global stage. Just this week, Amazon ordered employees to return to the office full-time, and it’s possible a lot of other businesses may soon follow suit.

“This sends the message: ‘We trusted you then; you stepped up and productivity went through the roof… but now we don’t trust you.’ That’s a rather negative message.”

But a subtler factor that could be contributing to lower engagement and innovation levels among employees can be found in the way leaders are talking to their workforces about AI.

“CEOs have been really bullish on generative AI. There has been lots of investment in that space with a very distinct desire for growth.”

These leaders aren’t just looking for the type of growth that stems from “sharpening the pencil and looking for efficiencies”, says McEwan. They’re seeking ambitious, top-line growth in the form of new products, markets and business opportunities.

“Leaders have delivered the message that technology is the way to get that kind of growth.”

This can tap into the age-old fear that technology might replace employees’ roles, and, at a more subconscious level, it can also send the message that employers don’t see their human workforce as a key driver of innovation and growth, says McEwan.

“It sends the message: ‘We don’t need you.’ During the pandemic, leaders didn’t really have to be inspiring. What they had to be was caring and understanding. But now that it’s all about growth, it’s almost like leadership has lost the art of how to inspire and motivate the workforce.”

To combat this, HR practitioners can champion the mindset that growth and innovation are going to come from the human workforce.

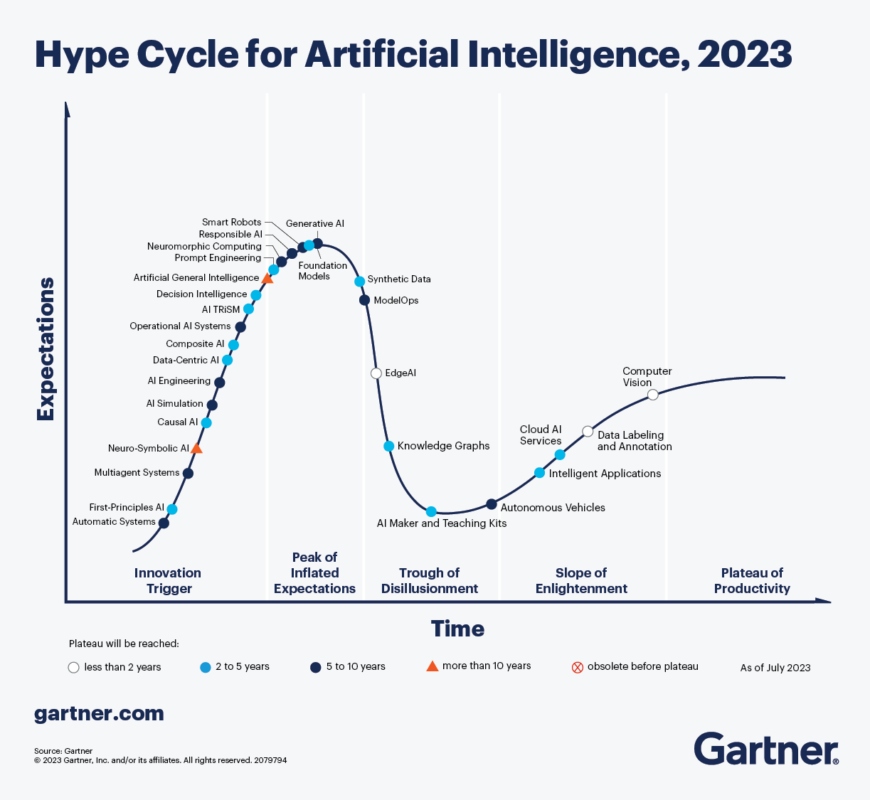

“AI is at that predictable part in its adoption curve where it’s difficult, expensive and intensive, and it’s not generating [much] return on investment – yet. That could be a couple of years away, maybe more.”

“In the meantime, how is an organisation going to grow if the big bets aren’t paying off in the short-term? It’s going to come from where it’s always come from: the willingness of your workforce to go above and beyond. At the moment, the workforce is not feeling confident that they have the environment and climate to be able to do that.”

A huge part of leaders’ job is now about inspiring the workforce, says McEwan, and reminding people how critical they are to reaching the organisation’s end goal.

“Shareholders expect [leaders] to… make tough decisions and be rational, objective and dispassionate. But the humans that work for them expect them to be human, authentic and caring. That can feel like an impossible task.

“That’s showing up in the fact that people don’t want to be managers anymore, because you have to carry cognitive dissonance 24/7 to be a leader today.”

This is where training that equips leaders with the capabilities, behaviours and skills they need to lead a workforce in 2024 and beyond becomes mission-critical.

Workplaces are not delivering on their tech promises

Another factor weighing people down is their experience of technology at work.

Despite promises of ambitious, aspirational growth agendas fuelled by cutting-edge technology, McEwan notes that many employees are still suffering through clunky, old-school technology at work.

“Their experiences with technology outside of work are magical, but when they step into work, it’s pretty uninspiring. People are like, ‘Well, I’m still stuck in meetings all day and working with spreadsheets and Powerpoint.’”

“If you had a piece of machinery that had been running at 5000 revs for the past three and a half years, you’d be a little bit worried about the wear and tear on that. If you were then about to embark on another accelerated period of growth, you’d want to make sure that equipment is up for the task.” – Aaron McEwan

And while employers are holding AI up as the panacea to all workplace challenges, that’s not employees’ reality.

“Some employees have reported that, for example, using generative AI is actually making their job harder; it’s taking longer to do things.”

And, in many respects, the more impactful gains can be made outside of technology use.

“Some research studies on users of generative AI at work show that people are saving seven to 10 minutes per day in order to gain productivity. That’s not much, right? Cancel a meeting and you can quadruple that.”

Help employees to “see the point” of work

Post-pandemic and amid chronic financial strain, many employees have simply lost sight of the ‘point’ of work.

“It used to be that if you worked hard, you could buy a house, have a comfortable life and get your kids educated,” he says.

But that’s not the case for many employees anymore.

“A lot of people are now thinking, ‘Even if I work hard, there’s no guarantee that any of those things will become reality for me, so what’s the point of work?'”

This can be a challenging perception to shift, but the antidote lies in realigning employees with a sense of purpose and recognising and rewarding their role in the bigger picture.

“I’ve never met someone who doesn’t like getting a pat on the back for their hard work,” says McEwan.

“Remind people that this is an exciting journey. If they’re going to be part of the journey, they have to feel like they’re part of it. At the moment, my take is that the workforce feels like technology transformation is something being imposed upon them, rather than something that they are not just a part of, but integral to.”

Thanks @Katie for a great article. Packed with lots of food for thought and the pivot points for action.