It turns out we might need more money than we thought for a comfortable retirement, so should workplaces start utilising higher superannuation contributions as a retention tool?

Do you know how much money you have in your superannuation account off the top of your head? If you do, you’re in the minority. For the rest of us, our low engagement with our super balance often comes down to a lack of tangible reward in the here and now. Think about it, what would excite you more? If I told you I was planning to bake you a cake for your birthday in three months time, or if I waved a fresh slice underneath your nose?

On the other hand, with the superannuation assets under management in Australia totalling a whopping $2.7 trillion as of December 2018 (fun fact: the ABC says that’s enough to buy all companies listed on the ASX), and superannuation set to become a more contentious political issue than it already is, employers might start to think about how they could utilise increased contributions as a tool to attract new talent and retain existing workers.

But are perks that only pay off in the future good enough?

A brief history of super

A recent 7:30 Report series on superannuation highlighted that employer’s superannuation contributions, at currently legislated rates, won’t be enough for the average Australian to retire on.

Plans laid by former Prime Minister Paul Keating to increase employer’s payments to 12 per cent by 2000 were derailed by the Howard government. As it stands incremental growth to employer contributions will now commence in July 2021, and is planned to meet Keating’s original 12 per cent target by 2025, decades behind the original schedule.

“Should the upcoming Budget demonstrate an early pathway to surplus, this provides an opportunity to accelerate the move to 12 per cent sooner, rather than later. Each year we delay is costing Australians superannuation savings that could help improve their retirement outcomes,” says ASFA CEO Dr Martin Fahy.

It’s not just older workers (250,000 Australians will retire this year) that we need to consider. While increased payments are likely to capture the attention of older workers, it’s the younger ones that would reap the most reward from such a policy.

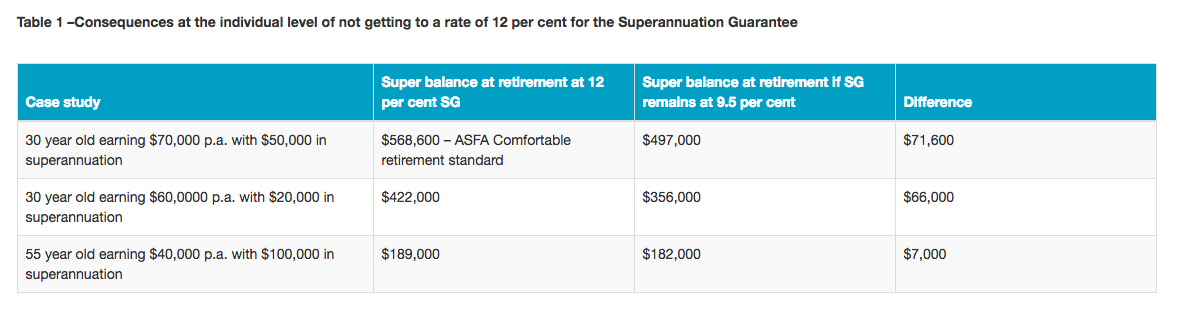

ASFA reports show that the average 30-year-old earning a $70,000 salary (the national average is $82,436) stands to lose $71,600 if they retired at 67 if the super guarantee remains at 9.5 per cent. Bringing the target forward by two years alone would boost their savings by $7000.

Some organisations are already contributing more. Many people working in the public service sector – which are highly-unionised – receive superannuation contributions of 10-12 per cent. And some university jobs can go as high up as 17 per cent.

“Each year we delay is costing Australians superannuation savings that could help improve their retirement outcomes.” – ASFA CEO Dr Martin Fahy.

More money now or more money later?

“The problem in superannuation is this – for most people they don’t choose to go in to it. The money is taken out of their wage by law. They know they can’t get hold of it for 20 or 30 or 40 years. They don’t feel as if it’s theirs,” former treasurer Peter Costello told the 7:30 Report.

That is a commonly thrown around reason for disengagement in super, especially with regards to younger people. If this is true and the benefits of superannuation are seen to be too far into the future, then it’s safe to assume most workers would not see increased contributions as a workplace perk, but more of a necessary evil.

Our brains are programmed to prefer immediate rewards, with research showing that the part of our brain that focuses on emotions responds very positively to instant gratification.

“Some people don’t see the value in having patience during difficult times or working toward a goal; they want to lose the weight now and would rather buy the latest, greatest cell phone than save for retirement,” says psychotherapist IIene S. Cohen for Psychology Today.

What does HR think?

“Broadly, I don’t see it as being the best retention and engagement tool because of the long run of time before an employee is able to access that money. There are a whole range of reward methods and I think it’s worthy of being in that toolkit, but it wouldn’t be the first one I’d call on,” says James Hancock, business director at Making Work Absolutely Human (Mwah).

From an investment perspective, he agrees that it makes perfect sense that employees should want a benefit like this, but that’s not always how it works.

“There can be a little bit of short-termism mindset from some people and that comes through on things like incentives. If I said you can have $5 in ten years or a dollar today, what would someone take and why?”

He also notes that for someone who is entering the workforce for the first time, the traditional approach to super could change by the time they retire.

“Considering how opaque the future looks, it makes it hard to say this is the thing we should turn to as an engagement tool,” Hancock says.

Where he can see it working as a retention or attraction tool is in organisations where base salaries aren’t competitive with that of larger corporates, or transient workers.

“There are a lot of pay structures out there. If you were to compare and contrast, you could look at an entrepreneurial/start-up company. Incentives there might look like lower base pay but equity in the business, which aligns that person out to growth, and gives stability for that company of its personnel. On the flip side, a more established corporate might mix cash bonuses with long and short term cash and equity incentives.”

Employer and employees alike shouldn’t put all their eggs into one basket, says Hancock. Just as an employee should diversify their investment portfolio, so too should employers when it comes to the engagement and retention tools they rely on.

Not just a perk

On the other side of the coin, companies that are seen to care about their employees’s retirement wellbeing are likely to attract candidates who place ethical organisations at the top of the pack. We know millennials in particular care about this, and they’re soon to make up 75 per cent of the entire workforce.

So you’re not just looking after individual employees when you increase super guarantee, you’re also strengthening your employer branding. Although some experts suggest that even the progressive 12-12.5 per cent being offered by some companies isn’t anywhere near enough.

Susan Thorp, professor of Finance at the University of Sydney told 7:30 that in order for people to live independently of the aged pension, “they would need to start contributing super at a rate of about 18 per cent at the beginning of their working life and contribute at that rate all the way through their working life”.

That would mean most of us are already far behind the eight ball and could potentially shock employee’s into action. While they might not have cared so much for the health of their superannuation balance beforehand, this information might change their mind, and packing information such as this into your employment branding means you could get great millennial staff fighting to get their feet under your desks.

“They would need to start contributing super at a rate of about 18 per cent at the beginning of their working life and contribute at that rate all the way through their working life”– Professor Susan Thorp.

Alternative perks

The Australian superannuation system is one that’s highly beneficial for some and not so much for others.

Ian Silk, CEO of AustralianSuper – a top ten Australian industry fund – told the 7:30 Report that for well paid, full-time workers in a good fund, it’s “a terrific system for you. But if you’re a part-time worker on a low income and you’re in a poor fund… the system is not working as well for you as it might.”

With 36 per cent of the working population thought to be working in part-time roles, the conversation about retirement savings in the workplace is more important than ever.

The 7:30 Report spoke with retired journalist Peter Bastick, who says he was personally negligent for not paying enough attention to his retirement savings. He says super just wasn’t on his radar and now he doesn’t have enough money.

His story is all too common of those in his generation. Employees like Bastick only started accruing superannuation payments towards the end of their careers, when the compulsory employer contribution scheme was introduced by the Keating government in 1992.

“If you truly want to become independent of the government, a self-funded retiree, live off superannuation, you’re going to have to put your own money in,” says Costello. This point is very valid. Employees do have a responsibility to think ahead and plan accordingly for their futures, but when looking at former employees like Bastick, you have to wonder if there was a point where his employer should have stepped in.

“Providing staff with education and information, particularly about the insurance they receive within their super, the choices available to them and the contributions made on their behalf, will make a big difference later in life,” Fahy told HRM.

“This can be a real differentiator for employers trying to attract talent in a tight labour market. We know from experience that employees value these extra savings a great deal, particularly when faced with rising living costs that make it difficult to set aside discretionary savings. If you’re an employer offering a higher rate of superannuation when others aren’t, you can attract higher quality staff and increase loyalty.

“Of course, where employees can save on top of their employer’s contributions, a little can go a long way. Contributing an extra say, $50 a month, early in your career could add tens of thousands of dollars to your final retirement savings.”

Should HR be taking a more leading approach in employees’ superannuation? Hancock thinks HR’s role is to empower staff with knowledge.

“Giving people a greater awareness of what’s out there and what they should be thinking about – giving them a stronger financial literacy – is where a lot of the big organisations are playing. It might not be that HR has to keep up to date with an employee’s balance, but instead give them information about how much they should have for their age and tenure. There are plenty of online calculators that can do that.”

He says it’s often a conversation that’s had with those entering their final years in the workforce and while some organisations might be targeting young new starters, it’s not widespread enough.

“A lot of big organisations have graduate programs and perhaps this is something that should be included in their onboarding to the company… and their onboarding into working life.

“It’s not just about the monetary factor, it’s setting these behaviours in employees early. That might not just apply to super. It could be building a share portfolio or simply investing in savings. Encourage employees to take charge of their financial future.”

It’s thought that in order to be completely independent of the Age Pension, individuals would need $1 million in savings. To say that most people feel daunted by that fact would be an understatement.

“Reliance on a part Age Pension during the course of retirement is a very reasonable outcome for both individuals and Australian governments. Our Age Pension bill in total remains a very modest proportion of GDP and is not set to increase. ASFA has estimated that a single person needs $545,000 and a couple $640,000 to achieve a comfortable standard of living in retirement,” says Fahy.

Are higher employer contributions a draw card for you? Or is your organisation already offering above the national standard? Let us know in the comments below.

Learn how to stand out from the pack and source the very best talent with AHRI’s short course ‘Attracting and retaining talent’.

Where this comes undone is the government’s maximum contribution threshold which is currently set at $25,000 per annum. If an employee is receiving 9.5% SGC + 3% employer contribution (for example) and is salary sacrificing, this cap is quickly reached and the benefit becomes redundant being consumed by PAYG. The government needs to look at indexing or increasing the maximum contribution threshold to enable emplioyees to save for retirement. It was $35,000 which was feasible bu $25,000 is untena

I agree with Mark. I’m no economist but I find it strange that there is a cap on employee contribution towards their own superannuation fund. I have a family of seven and two mortgages to navigate, so I am not salary sacrificing anywhere near that annually, but once the kids have moved out and the house is closer to paid off, I will ramp it up. I know many colleagues who are close to retirement hit the cap half way through the year and it frustrates them that they can’t pump more in.

Thank you for your super article on whether higher super can be used to retain employees. In your article you raised two key reasons it might not be: • People seek more immediate gratification • During the early years of most people’s employment they tend to earn less and need cash now – not later. To counter the above you stated, “companies that are seen to care about their employees’ retirement wellbeing are likely to attract candidates who place ethical organisations at the top of the pack” which aligns with the millennium workforce. I have two concerns with this argument.… Read more »