In light of the recent Australian Federal Police tragedy, it’s worth thinking about how we talk about workplace suicide.

The Australian Federal Police has had four suicides happen in AFP offices in the last two years. An anonymous police advocacy spokesman told news.com.au of his concern that “officers might be trying to send a message by taking their lives in the workplace”.

This made me think about how people talk about suicide. Do we look for such messages? Should we? While it’s inappropriate to speculate too much about what’s happening at the AFP, what we can do is try and broaden our knowledge of workplace suicide.

The toughest conversation

Except for suicide bombings, we don’t tend talk to talk about suicides differently. This is partly because each suicide is just really hard to talk about. It’s not only emotionally difficult, it also means different things depending on who you’re talking to and where they’re from.

In her study, Colorado State University professor Silvia Canetto says cultural factors determine what we call suicidal. For instance, while more men die from suicide, more women attempt suicide. “If one includes only suicidal death, suicidality might seem a male problem… However, if one counts non-fatal suicidal behaviour as suicidality, suicidal behaviour reveals itself as a female problem, because females outnumber males in total number of suicidal acts.”

On a more intimate level, every suicide is so painful and disturbing to those it directly affects that many don’t have the inclination or emotional balance to think about it too thoroughly. And for people who are affected indirectly, the issue is simultaneously too sensitive and too distant. It’s no wonder each of us prefer to make sense of the act with whatever story is most comforting.

This extends to wider social norms. When I was young, I was told suicide was selfish. Now we’re more likely to tell each other that the root cause of suicide is mental unwellness, usually depression. Each narrative has its benefits. The former tells us it’s okay to refuse sadness and feel bitter. The latter, that the agony of the departed went with them.

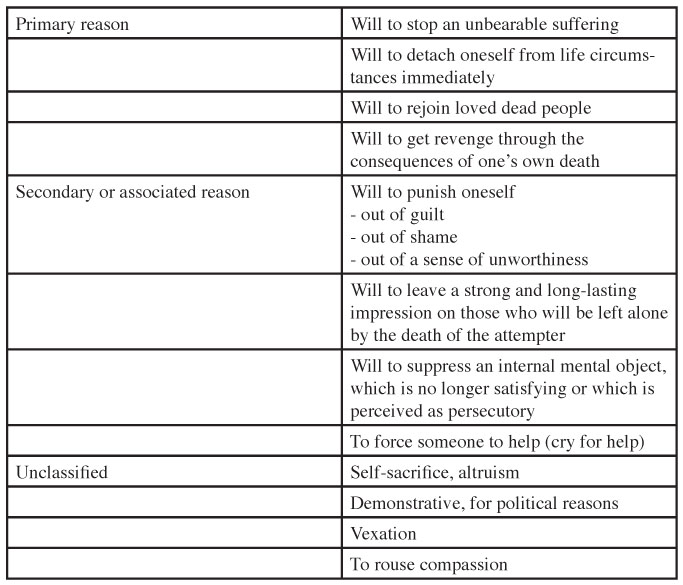

The truth is there’s rarely a single motivation for any suicide, let alone a single cause. Psychiatrist Antonio Preti, in his article On Killing by self-Killing, lists “motivations of suicide drawn from the case reports of survivors of severe suicide attempts”.

Since people are more likely to express culturally accepted reasons for suicide after attempts, the list isn’t authoritative. But it is interesting, as it catalogues primary and secondary (or associated) reasons we all know but rarely mention.

The reason we should strive to talk about each suicide with more clarity is to demystify each act. Getting better at talking about suicide gives us another tool to help prevent it. (And, from a media perspective, numerous studies have found that the frequency and manner in which the news reports on suicide can cause a copycat effect).

We should be able to distinguish differences. For instance, if someone takes their own life at work, it’s rational to assume they want to communicate something to the people in their workplace. Or, since suicide isn’t always or even usually rational, they could want to communicate with abstract notions, such as their organisation or their ‘work’.

Suicide over work

Some who have killed themselves have blamed work exclusively. In an analysis of suicide letters linked to 23 cases within French companies, Dr Sarah Waters, University of Leeds, says, “In these testimonies, suicidal individuals unequivocally blame work and workplace experiences as the cause of their self-killing and exclude personal or family circumstances.”

One testimony read: “I should however have everything to be happy, a loving wife, an adorable daughter. However, all this professional anxiety has encroached on my private life and I can no longer experience joy like before.”

Interestingly Waters says that the Japanese phenomenon of karo-jisatu (suicide from overwork) “bears similarities” to the ‘suicide waves’ of the three French companies she looks at in her article (for more on karo-jisatu, read this). So the idea of work being the primary factor behind suicide shouldn’t be limited to a single country.

Backing up this point, in a different study that compares workplace and non-workplace suicides in the US, researchers found different trends for both. Looking at the period between 2003-2010 they found that workplace suicide rates decreased until 2007 and then quickly increased (literature links increased suicide rates with the Global Financial Crisis, the authors say). Non-workplace suicides on the other hand showed a steady upward trend.

It should be noted that research has found risk factors for suicide are “universal across countries and culture” and include the presence of a mental disorder, a family history of psychopathology, and the effect of life events in the previous month. Those are fairly broad, and risk factors in general don’t tell the whole story.

As the US researchers state in their conclusion: “Occupation can largely define a person’s identity and psychological risk factors for suicide, such as depression and stress, can be affected by the workplace. Also, as the lines between home and work continue to blur, personal issues creep into the workplace and work problems often find their way into employees’ personal lives.”

What can you do?

There’s no ironclad workplace suicide prevention program. A meta study of several programs, both in Australia and the US, found there wasn’t enough data to draw definitive conclusions on what’s effective.

But they note that endorsement of a program by key stakeholders was key and that several programs stressed the “importance of having a multi-faceted, comprehensive and community-based approach that simultaneously operates at a universal level while also ensuring those at risk are able to be identified and provided with treatment in a timely manner.”

The call for a community-based approach shouldn’t be lost on us. One great workplace is not going to change our culture. So while it’s important to remember that, yes, we should certainly ask each other “are you okay?”, we should be prepared for the many different versions of “I’m not okay” we might hear.

Read more

If you would like to read more about how your workplace could start a conversation, HRM has written before about mental health at work. Including:

- A guide to coping with death in the workplace

- How workplaces can develop mental health literacy

- What workplaces can do to prevent suicide

- What they can do to help men’s mental health

- How organisations can help with the loneliness epidemic

- How HR can help with resilience

- How HR can help reduce bullying

- Why belonging is next on the HR and leadership agenda

Mental health is a serious issue, anyone needing support can call Lifeline on 13 11 14, and beyondblue on 1300 224 636.

Have an HR question? Access our online AHRI:ASSIST resource for HR guidelines, checklists and policy templates on different HR topics or ask you questions online. Exclusive to AHRI members.

Excellent article. Further to this important information I have read recent Australian research on causes of workplace bullying leading to suicide which identify the following: 1. Depression and anxiety global costs are estimated to be a high as $1 trillion U.S (P.A), 2. Collective well being cost $2 Billion, or 12% of GDP, 3. Top causes of psychosocial related injuries in Australia are: Bullying & Harassment, overwork/work pressure. And remember HR professionals, two of these, potentially three constitute breaches of both the FWA and WHS acts (including all harmonised legislation). The overwork should also be monitored by both WHS and… Read more »

It’s great that AHRI has put this firmly on the map to discuss, it’s shocking when suicide happens at work and it’s hard to know how to deal with it. One comment -a mental health nurse friend of mine said that the term “commited suicide” is an outdated one which harks back to the days when suicide (or attempted suicide) was a criminal offence.

First things first – it is good to see HRM covering this difficult topic. Having said that, please refer to MindFrame Media’s guidelines on responsible reporting on suicide, and consider editing certain terms out of the article, and or replacing some phrases with more appropriate phrasing: http://www.mindframe-media.info/for-media/reporting-suicide. Second – I reiterate Ciaran’s below comments – with a minor edit that the estimated direct and indirect cost to collective wellbeing in Australia is $211 billion (12% of GDP). With a median cost of $342K, about 1/5 of these claims cost more than $500K, the median time off work is longer than… Read more »

Brisbane AHRI has had Donna Thistlethwaite, a fellow HR practitioner, speak about her experience, and I know that she has spoken at other large seminars in Brisbane about suicide and the workplace. It was very powerful and impactful and I recommend her as a speaker on the topic. You can google Donna and her story which was featured on Australian Story.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-07/donna-thistlewaite-suicide-survivor-story-bridge/8753316