There’s a 15 per cent gender gap in the uptake of flexible work. We need to shift the narrative that flexible work is just for women, as plenty of men are seeking – and would benefit from – working reduced hours.

The Diversity Council of Australia’s (DCA) 2023 Inclusion@Work report, which is soon to be released, has revealed that flexible working is still the domain of the female employee.

In a sample of 3000 Australian workers, DCA found that 57 per cent of men had taken up some form of flexible work in the past 12 months, such as reduced hours, flexible start times or working remotely, compared with 72 per cent of women.

“Most people accept that women are primary carers of children,” says Lisa Annese, CEO of DCA. “If a woman asks to work in a different way so she can manage her responsibilities outside of work, that’s usually within the ‘normal’ expectations of how women behave,” she says.

But men who desire similar arrangements face a different reality.

Flexism against men

DCA found that one in four employees experience discrimination and/or harassment for choosing to work flexibly.

While this is slightly lower than rates reported in the 2019 Index (31 per cent), it still doesn’t align with where we’d hope to be, especially following the monumental shake-up of work post-COVID.

Men are feeling it the most, with 37 per cent saying they face discrimination/harassment when working reduced hours, compared to 24 per cent of women.

This discrimination/harassment could come in the form of snide remarks, missing out on professional opportunities or experiencing social exclusion, says Annese.

“They’re seen as not being committed to their careers anymore and as not having the requisite leadership capabilities. They’re behaving in a way outside of the stereotype of their gender and they are punished for that.”

Interestingly, when it came to flexible working arrangements in terms of location, not hours, there was a much smaller gender gap (15 per cent for women and 17 per cent for men) compared to the gender split for those who choose to work fewer hours (38 per cent of women and 21 per cent of men).

“Even though women do often face repercussions, it’s still usually easier for them to access flexible work even if it [has long-term impacts] on their career.

“For men, they’re up against a different challenge. People might say, ‘That’s strange that you want to work flexibly to look after children.'”

These biases come from both men and women, Annese adds.

“I had a woman at a leading organisation once say to me, ‘We’ve got this man and he wants to work part-time, but I know his wife doesn’t work.’ I said to her, ‘This isn’t something you’d say if it was a woman who was asking for flexibility. You wouldn’t be thinking about whether her partner was working or not.’

“She wasn’t malicious, she’d just never thought about it. We’re so wedded to those stereotypes, and that’s one of the biggest challenges for men. Their masculinity gets questioned.”

“A policy is a starting point. But policies don’t necessarily reflect culture. If the men in your organisation aren’t taking up flexible work, it means they don’t see themselves in that policy.” – Lisa Annese, CEO, DCA

Caring responsibilities

Of the people who had worked flexibly in the past 12 months, DCA found that three in four did so to manage caring responsibilities.

“Inequality at home is something we don’t talk about enough,” says Annese. “It prevents women from participating in the workplace; it prevents men from developing relationships with their kids.”

It’s a lose-lose situation. In fact, it’s a lose-lose-lose situation, because employers suffer too.

Research from Circle In, an employee benefits provider, surveyed 400 Australian dads and found that 72 per cent cite parental leave as a top consideration when choosing a job. Seventy-three per cent want to take parental leave, but only a third of their organisations offer it to them.

More broadly, research from Officeworks shows that 78 per cent of employees, regardless of gender, wouldn’t work for a company that didn’t have a flexible work policy.

“We’re seeing growing trends of men who really want to be active parents,” says Annese. “Especially younger men. They will seek out employers who can support [their flexibility needs]. And if that’s not you, you risk losing great talent.”

Companies doing it well

Annese calls out Deloitte as a trailblazing organisation in this space.

“They encourage all parents to take an active role in caring. They also continue to pay super during unpaid parental leave and offer coaching for the return to work, to help transition parents back into the workforce.”

Read more about how Deloitte supports working parents.

NAB is another organisation that’s leading the way in terms of flexible work options for employees of any gender.

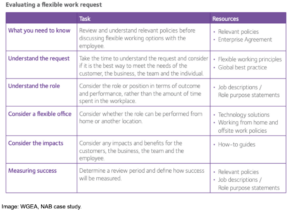

A case study published on the Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s website outlines how it champions flexible work for its 30,000 employees across Australia. This includes options for job-sharing, phased-down retirement, compressed work hours and flexible start and finish times.

It has also created a Flexible Working Toolkit for employees to research flex options and create flexible work proposals. This toolkit also includes training on topics such as how to stay connected when working remotely and communication tips for remote workers.

It also includes a checklist for its managers to use when assessing a flexible work request (see below).

Flexible work integrated into the system

To normalise flexible work for both men and women, Annese suggests making it “integrated into the system”.

“This way, when you work flexibly, you don’t fall off the career path or miss any opportunities.”

She also stresses that it’s important to build processes at a team level.

“When you are negotiating flexible working with an individual, it’s never just about the individual. It should never be a conversation that just happens between a manager and an individual.”

Teams need to sit down and come up with arrangements that will suit everyone, she says.

“[Ask about] how people like working, what’s going on for them outside of work, what’s happening at work, what the business non-negotiables are, how we need to resource the team or work so we can meet the challenges of our business.

“Create rules within your team, so everyone can work in a way where they can manage their life, but also meet the needs of the business.”

Beyond the policies

Many organisations have already done the groundwork to formalise their company’s flexible work approaches by creating a policy.

“But the issue isn’t the policy anymore. It’s what’s accepted culturally. It depends on the team you’re in and the managers you have.

“A policy is a starting point. But policies don’t necessarily reflect culture. If the men in your organisation aren’t taking up flexible work, it means they don’t see themselves in that policy.”

Demonstrating visibility at a senior level is what will move the needle, she says.

“If a young man doesn’t see anyone who’s senior working in a flexible way, there is no way he’s going to put his hand up to be the first one – even if the policy says he can.”

People often ask, ‘So what can HR do about it?’ But Annese says that’s not the right question to ask.

“It’s about what every individual leader does and anyone who manages people. How do you organise work? How do you structure your teams? What kind of culture are you building? How much agility do you have in [that team]?

“HR’s role is to help [those people] build [their] capabilities. Employers can’t defer to HR to fix the problem, because that’s leaders abdicating their responsibilities and obligations and missing an opportunity to create an inclusive team environment.”

Need help taking steps to reduce bias and support inclusion in the workplace? AHRI’s short course will provide you with techniques to create a diverse and inclusive workplace.