Expectations shape attitudes, attitudes drive behaviours and behaviours deliver results, says global HR leader, Dave Ulrich. That’s why it’s important for HR to manage the ‘expectation paradox’.

Expectations often determine how people respond to certain situations. Expectations come from many sources – self-talk, upbringing, experiences, biases, peer groups, lifestyles, and so forth – and they can impact relationships, daily routines and work.

For example:

- Lower-end restaurants, hotels and stores may have far fewer customer complaints than their high-end counterparts because of customers’ expectations.

- Two leaders each receiving a 4.2 (out of 5.0) on a 360 feedback score may have very different responses based on their expectations of themselves.

- An executive publicly promised 15 per cent growth and 12 per cent profit. But when results were a remarkable 12 per cent and 9 per cent respectively, the company lost market value because of high expectations set by the executive.

Lowering and raising the expectation bar

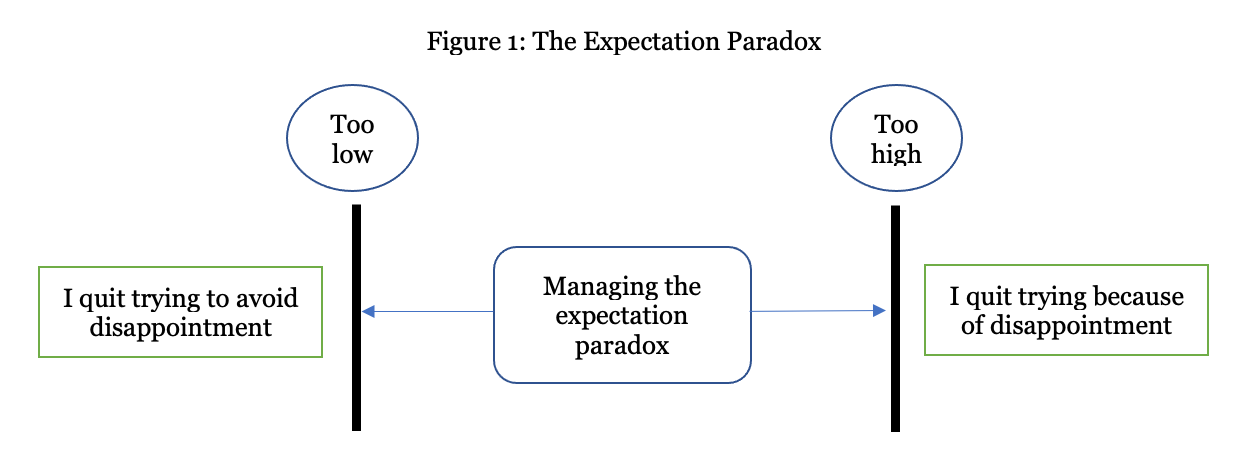

How do we manage this expectation paradox of lowering the bar to avoid disappointment and raising the bar to reach new heights (see figure 1), and drive the right behaviours to deliver desired results?

We lower the expectation bar as a defence mechanism to temper disappointment. An employee who does not expect to receive a promotion is less disappointed when passed over. A customer is less disappointed that a product or service fails by not having high expectations. (We can hardly be disappointed with the $1.99 breakfast.) The danger of the low expectation bar is that despite being less disappointed, we are still unsatisfied: employees quit trying and customers quit buying.

We raise the expectation bar to try harder, do more, take risks, grow and deliver exceptional results. We tell ourselves, our kids and our employees: “You can do anything.” Leaders set aspirational visions of being the best and identify stretch goals or assignments to increase effort and accomplish more than is normally possible.

The danger of the high expectation bar is that missed expectations can lead to disappointment and a pattern of failure where, again, employees quit trying and customers quit buying.

Four ways to manage the expectation paradox

Let me suggest four tips to manage this expectation paradox so expectations lead to positive attitudes, behaviours and outcomes in both personal and professional settings.

Tip 1: Failure is an opportunity for learning.

Carol Dweck’s focus on a growth mindset suggests redefining failure as an opportunity to learn. I liked this message so much, I had a pillow made for my wife (and me) that we have on our couch as a constant reminder.

When expectations centre on learning and growth more than outcomes and results, we make progress. Struggling in a relationship or missing a goal is normal and enables learning.

When a relationship ends, rather than blaming, we can learn how to improve future relationships. When a personal or business goal is missed, we can run toward the failure and learn from it. When our expectations are about failure being an opportunity to learn, we turn a vicious circle into a virtuous cycle.

Tip 2: Get real.

I have coached well-intentioned aspiring leaders who want to have a great marriage, be actively involved in raising kids, serve in community organisations, consistently be in the top five per cent of performance ratings, be promoted rapidly, and run a seven-minute mile.

Achieving all of these is not likely, at least not all at once. My mentor and colleague C. K. Prahalad taught, “Your aspirations should exceed your resources, but not too much.”

A close friend is proud to have run (walked) a fifteen-minute mile because that marked progress even if not perfection. Not everything worth doing is worth doing well, and, as my wife has taught me, some things are so important to do that they are worth doing poorly as we slowly learn to do them better. Realistic expectations enable real progress.

Tip 3: See and seek patterns, not isolated events.

When an aeroplane flies from point A to point B, it is almost never on the direct line between these two points. It is constantly adjusting and making course corrections. But the plane will still arrive at point B.

In relationships and at work, overstating a single event can be dangerous. A leader said, “I tried asking my team their view of my leadership skills based on a single event, which was not as helpful as their observing my style with many events over time.”

“When our expectations are about failure being an opportunity to learn, we turn a vicious circle into a virtuous cycle.” – Dave Ulrich, Rensis Likert Professor at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan

Managing expectations means focusing on a longer-term goal (arriving at point B or learning a new leadership style). Isolated events may deviate but should not derail that process. Expectations are too often short-term, quick fixes, which, like fad diets, don’t often work (been there, done that).

Tip 4: Be humble and engaging in public; be ambitious and driven in private.

Coaches often give different talks to players in a private locker room than to the media in public. In private, they remind players of their gifts, hard work, and likelihood of victory. In public, they acknowledge the quality of the opponent and the challenge of winning.

Likewise, what we tell ourselves does not have to be the same message that we broadcast to others. Quiet and personal confidence does not have to become public bravado to make progress. I can have very high personal expectations of what I believe I can and should be able to do. But my public statements engage others and share credit.

Expectations shape all aspects of our lives.

In relationships, as we manage expectations about our companions and friends, we can build sustainable social connections that enrich us. When learning from failure, embracing realism, seeking patterns, and fostering private commitment characterises our relationship expectations, they will likely be more fulfilling and meaningful.

At work, leaders who manage employee’ expectations help them reach their potential. Employees who manage their own expectations learn, grow and find fulfilment from work. I have friends who have abandoned their organisation because they expected it to be perfect. Managing relationships requires expectation patience – so does participating in an organisation.

As we manage expectations about our identity, strengths and passions in our personal and daily living, we can be more at peace with who we are than at odds with who we are not. So, what do you expect? Of yourself, your colleagues and your organisation?

Dave Ulrich is the Rensis Likert Professor at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, and a partner at The RBL Group, a consulting firm focused on helping organisations and leaders deliver value. This is an edited version of an article that was first published on Ulrich’s LinkedIn profile. View the original article here.

Need support enhancing your HR capabilities? Take AHRI’s capabilities analysis test to learn where you can enhance your skill set and receive a personalised report outlining what your AHRI learning journey could look like. Learn more here.

Another example of bizarre phraseology. “HR” is increasingly moving into the area of ‘esoterica’