In order to position our organisations for success in the future of work, we first need to address the elements of work that are broken, say experts at AHRI’s National Convention and Exhibition.

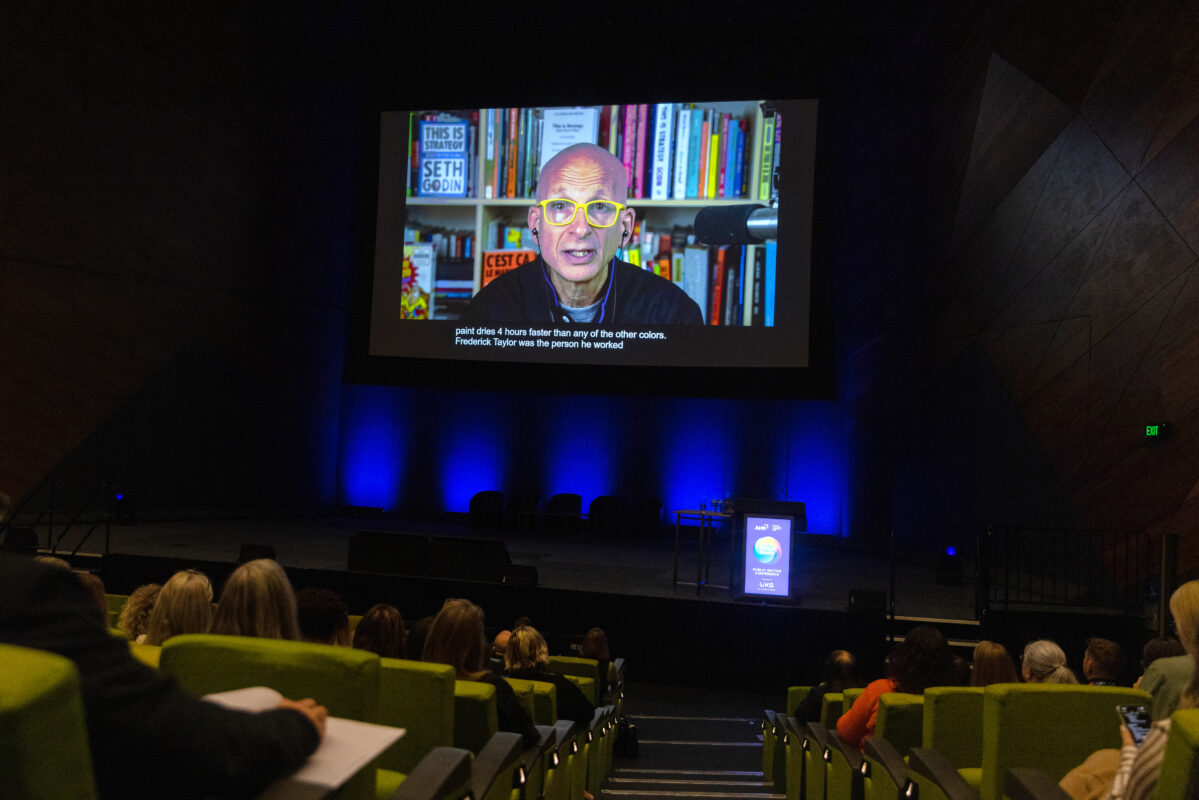

What’s the difference between a lake and river? This was a question Seth Godin, best-selling author and entrepreneur, posed to the audience at day three of AHRI’s National Convention and Exhibition last week.

The difference is the current.

“When I’m canoeing on the Hudson River with the current, it’s pretty easy. When I’m going against the current, it’s extremely difficult. This is culture,” says Godin.

Too often, we think our organisation is a lake, he says. But, as all HR practitioners can attest, work is rarely smooth sailing. The trick is to learn how to work with the currents.

Part of that means breaking away from our traditional views of work, which have been instilled in us since the early-1900s Henry Ford era.

“Henry Ford transformed work more than almost any single human. He did this by producing cars 75 per cent cheaper. You may have heard the expression, ‘You can have any colour you want, as long as it’s black.’ Henry Ford didn’t say that because he likes black. He said that because black paint dries four hours faster than any other colour.”

This mentality sparked decades of managers and workers seeking to achieve optimal productivity. From designing a faultless assembly line in the 1910s to the myriad modern-day experts who promote ‘ultimate productivity hacks’, we’ve become borderline obsessed with self-optimisation, to the point where, in many instances, our experience of work and our wellbeing is coming under strain. This, ironically, damages our output – the very thing we were working so hard to enhance.

We need to stop treating people like machines, says Godin, and instead design what he calls “workplaces of significance”.

After surveying over 10,000 people across the world and asking ‘What’s the best job you’ve had?’, he analysed what we believe goes into making a significant work experience.

Interestingly, employers assumed it would be:

- That work wasn’t too difficult

- That work wasn’t too exhausting

- That people were paid generously

- That people were bestowed with authority to “tell people what to do”.

“[These answers are] what we’ve built management around,” he says.

However, when cutting the data to view the results from the employee perspective, it told an entirely different story. Employees said that their ‘best job’ was when:

- They had more responsibilities than they expected

- Their team was building something important

- People treated them with respect

- They learned a lot.

What gets in the way?

While most people reading this will agree that a workplace where people feel respected and learn interesting things is a good thing, the challenge is that there are often barriers that get in the way of HR’s hard work in achieving these cultures.

According to Godin, these barriers include:

1. False proxies

At work, we’re relying on false proxies all the time, says Godin.

“[We say], ‘Oh, that person went to a famous college,’ or, ‘That person is of the same social status as me’… None of these things are related to whether they are good at their job, yet we think our job is to sniff out these proxies.”

An antidote to this, beyond the important work of uncovering our own personal biases, is to engage in practices that pull us out of our status quo approach.

“Criticise the work instead of the worker, work relentlessly to establish standards, [and] create conditions for those standards to be met.” – Seth Godin, best-selling author and entrepreneur

Godin uses the example of Greyston Bakery in the US, which practises open hiring.

“Open hiring is a clipboard at the front desk where anyone can walk in and put their name and phone number on the clipboard. When a job opens up, the next person on the list gets the job – it doesn’t matter if they’ve been incarcerated.

“You have two weeks of training [to show that you can do the work] and if you make it, you get to stay.”

As a result of this approach to hiring, turnover at Greystone is extremely low, and while some other organisations have since adopted the open hiring approach, such as The Body Shop, it’s not spreading quickly – because, as Godin says, “We like false proxies; we like feeling like we’re in control.”

You can read more about Greyson’s open hiring approach in this HRM article.

2. We focus on obedience instead of standards

Many workplaces impose strict rules on their teams – which can feel prescriptive – rather than setting expectations around the standards of behaviour.

“Criticise the work instead of the worker, work relentlessly to establish standards, create conditions for those standards to be met, and build a culture where people can honestly talk about whether or not we have met the standards, so we can make it better.

“That’s what happens in science. That’s what happens in places that are focused on Six Sigma quality. So if you’re working in a hospital and the patient is dying, they don’t say, ‘You’re a bad doctor,’ they say, ‘There’s something about our process that isn’t working.’ We don’t hide it, we highlight it.”

3. We don’t give frontline employees enough agency

Godin told the story of Nordstrom, a US retail store that “sells stuff that you could buy somewhere else for less” but earns customer loyalty by offering premium service.

“So a guy walks into a Nordstrom store – he’s 75 years old. He walks up to the tie counter where they sell $150 neckties and he puts a snow tyre down on the counter and says, ‘I need my money back. I bought this here but I don’t need it.’

“The clerk – a person [in the organisation] with the lowest status and lowest pay – reaches into the till, hands the guy a couple of hundred bucks and says, “Thank you for shopping at Nordstrom”. The thing is, Nordstrom doesn’t sell snow tyres.”

This was a Nordstrom in Alaska which had taken over from a different store that used to sell snow tyres.

“Nordstrom tells this story over and over again as a way of signalling to its [frontline] employees that while they might be low on the hierarchy, they are the most important person there and they have the authority to make the customer happy.

“That story is worth millions and millions of dollars and it only cost them a few hundred dollars to refund a tyre.”

He shared another example of a luxury hotel chain that gives all its housekeepers a $250 budget to use whenever they see a customer who is unhappy.

“No questions asked. Giving agency to people on the front line costs you almost nothing. The lifetime value of one of your customers could be $100,000 and you just saved them for $250.”

4. We’re obsessed with meetings

This last point will come as no surprise to anyone, but it bears repeating: the volume and inefficiency of our meetings are preventing us from creating good employee experiences.

“They get in the way of people doing their work. If you have a meeting culture that doesn’t create the condition of forward motion, then that’s on you [to change]. Humans don’t want to sit in a room listening to someone prattle at them. If you can send a memo, send a memo.”

Read HRM’s article on the psychology behind why we find it hard to stop attending meetings.

Godin refers to the way Amazon runs its meetings.

“Everyone at the meeting gets the memo in advance. Anyone who agrees [with the memo] doesn’t have to go to the meeting. If you have questions about it, then you go to the meeting and ask the person who wrote the memo questions, and then a decision must be made.

“So if you’re not willing to… state your case, if you’re not willing to push back and [productively] argue your point, don’t go to the meeting. You can do this in your organisation tomorrow and what people will discover is that it’s thrilling.”

Trust in our institutions

Creating a workplace of significance requires leadership teams and cultures that can be trusted. And, as this saying goes,”Trust takes years to build, seconds to break and forever to repair.”

This topic was discussed in the first session of the public sector portion of AHRI’s National Convention and Exhibition. The question posed to the audience was: What creates the cultural conditions for corruption and distrust to thrive in an institution?

Two people who are well-placed to answer this question are investigative journalists and authors Nick McKenzie and Chris Masters who, in 2018, broke news of alleged war crimes committed by one of Australia’s most decorated soldiers, Ben Roberts-Smith, during his service in Afghanistan.

Following a lengthy court process after Roberts-Smith sued the journalists for defamation – a process that spanned years – in June 2023, the allegations were found to be true.

“What blows me away… is how seemingly very robust institutions host, enable and facilitate scandal,” says McKenzie.

But it does happen. Beyond the special forces, many industries often find themselves embroiled in scandals that likely could have been prevented. Data security breaches, sexual harassment claims and toxic bullying cultures are, unfortunately, rife in our nation’s institutions.

It’s important that accountability is spread across the entire leadership team, all of whom have a responsibility to identify and address cultural issues before they snowball into greater challenges, says McKenzie.

For example, McKenzie refers to the “anything goes” cultures that were perpetuated within soldier groups in Afghanistan.

“I believe that the leaders didn’t know [about these war crimes]… [But] leaders need to be held to a higher standard.”

Masters agreed and said that while “there was no evidence to link fingerprints of leadership [to] these war crimes, there was clearly an absence of curiosity”. This meant that behavioural norms became more important than the rule, he added.

“All bad news rises to the surface eventually, so it’s much better that you deal with it rather than having it on the front page [of a newspaper].” – Nick McKenzie, investigative journalist and author

And, as McKenzie notes, once the door of poor behaviour is slightly ajar, “It can easily be pushed open.”

So how can HR create cultures whereby leaders are aware that, ultimately, when it comes to accountability, the buck stops with them?

One suggestion McKenzie offered was to facilitate cultures whereby the act of raising complex, challenging issues to leadership teams – or whistleblowing – is rewarded and appreciated, rather than seen as going against the business.

“How do you incentivise the whistleblower? So, in the public sector, that might be getting together once a year and saying, ‘I want one piece of constructive criticism – that’s one of your KPIs. This is your chance to tell us [if something is wrong] and you will be marked up for that.'”

Getting on the front foot

When addressing challenging situations or scandals within a business, both Masters and McKenzie say it’s always best to get on the front foot and address the issue quickly, even if your inclination is to deal with it behind closed doors.

“All bad news rises to the surface eventually, so it’s much better that you deal with it rather than having it on the front page [of a newspaper],” says McKenzie.

He refers to Channel Nine as an example of this. Following the sudden resignation of a high-profile executive in March this year, Nine kept quiet about the truth behind his resignation.

However, eventually news surfaced about what has now been described by some as the “predatory behaviour” of this executive which was, apparently, known and tolerated for years.

“[They should have] announced his departure in these terms – both internally and externally. ‘This [person] has left the organisation because of serious concerns about his behaviour. We take sexual harassment and workers’ safety seriously and the evidence of that is the fact that he’s left,'” says McKenzie.

Because they didn’t do that and instead tried to deal with the situation behind closed doors, they’ve faced serious reputational damage as a result, he says.

“As an HR executive or leader, once you own a scandal, you can control it.”

Interested in hearing more insights from AHRI’s National Convention and Exhibition? You can read HRM’s insights from day one here and day two here. Keep an eye out for more insights in the upcoming weeks. Subscribe to our daily newsletter to stay in the know (click ‘subscribe’ button on top right-hand corner).