Office politics often gets a bad rap – but that’s because its function within a workplace’s ecosystem is commonly misunderstood. It’s only when internal politics turns sour that it becomes an issue.

When people hear “office politics”, they often default to the negative – associating it with underhanded tactics, poor intentions and destructive behaviours.

While internal politics can take a negative turn, it’s often far more nuanced. In fact, in many ways, it’s a crucial skill for HR practitioners to master.

Any movement of work through an organisation that doesn’t occur on a straight, clear chain of authority requires some level of office politics, says Jen Overbeck, Professor of Management and Associate Dean of Research at Melbourne Business School and researcher into the effects of power and status on interpersonal and group dynamics.

“If the boss says we’re working towards a 10 per cent increase in revenue targets, that’s an exercise of power. But when someone within the organisation pushes to reallocate resources – say, advocating for greater investment in AI development – without formal authority, they’re having to navigate organisational politics.

“It’s the bread and butter of what organisations do every day. Zeroing in on how it’s done is what makes the difference.”

What this article covers:

Need to read this in a hurry? Skim the ‘idea in short’ sections to get the gist quickly.

Good versus bad internal politics

Idea in short: Good internal politics helps to move things in a positive and strategic direction. Bad office politics derails progress and can be extremely harmful to workplace cohesion and meeting expected outcomes.

Bad office politics:

“Throughout my career, I’ve seen internal politics take many forms – power struggles, favouritism, information hoarding and toxic self-preservation,” says Barbara Fidock FCPHR, Employee Experience Lead at Iress and AHRI Queensland State Councillor.

“One of the most challenging was a CEO who rejected diverse perspectives, surrounding themself with ‘yes-people‘ who undermined each other to stay in their favor. This stifled innovation, eroded trust and silenced employees.”

Fidock says the warning signs of harmful office politics are clear: a lack of transparency, favouritism, exclusionary cliques, and decisions driven by personal agendas rather than merit or what’s best for the organisation.

“When employees feel sidelined, disengagement rises, collaboration breaks down and innovation suffers. Fear-based cultures, where people hesitate to voice concerns or take risks, only reinforce these issues, leaving HR in a reactive role rather than a strategic one.”

Navigating these situations is “extremely difficult”, says Fidock, as these behaviours often occur in environments with a lack of trust and psychological safety.

“Also, if not handled strategically and with a measured approach, quite often your own role can be at risk,” she adds.

What encourages people to engage in toxic office politics? Overbeck says there are myriad reasons.

“People can play a negative politics game because of their kind of ideological belief system or their personality – there are lots of things that make people more conspiratorial. They might believe it’s a… competitive world where you’d better lock up your own advantages or somebody else will take them all.”

“When employees feel sidelined, disengagement rises, collaboration breaks down and innovation suffers.” – Barbara Fidock FCPHR, Employee Experience Lead at Iress

Making an inference based on some data she’s seen, Overbeck says only around 10 per cent of people engage in corrosive internal politics in an intentional way.

“There are plenty of people who may have better ways of working, but they haven’t seen those approaches succeed around them. Maybe they’ve had negative experiences in their current organisation – leading them to believe that success requires gossiping, saying one thing in meetings but doing another, or undermining colleagues.”

Some take a different approach, rigidly adhering to rules to the point that progress stalls for all involved, she adds.

“People might adopt these strategies because they feel that making a straightforward case and engaging openly isn’t rewarded in their work environment. And they might be right or they might be wrong. But that’s where these behaviours often stem from.”

Good office politics:

Some of the most effective people in an organisation are those who understand how to navigate internal politics at work, says Overbeck. For example, when rolling out a change, a politician knows exactly who to engage with to help get the idea over the line.

“Take the introduction of generative AI tools, for example. If we decide to implement AI to save labour costs instead of making planned new hires, I need to anticipate who will oppose the decision and who will embrace it.”

A strategic approach involves working with opponents to address their concerns, helping them see the benefits, and managing their emotions, she says.

“At the same time, I need to be working with the proponents – encouraging them to get people talking and role modeling what this new technology can do. A good politician has a good read on who these people are and understands how to enlist them in productive ways.

“It’s about learning how to work in a complex and competitive yet collaborative system where we can play politics in a constructive space.

“A poor politician, on the other hand, maybe doesn’t think about those things. They simply push the change through – signing contracts, sending mass emails announcing the AI rollout and hiring freeze and assuming everything will work out. This often ends up being bad for the organisation.”

How to discern between the two types

Idea in short: The way people interact in meetings and communication channels more broadly can reveal whether power and politics are used constructively – open dialogue signals a healthy culture, while silence and backchanneling suggest dysfunction.

So how can you tell if someone is using office politics in a useful way? Overbeck suggests observing how people interact with each other in meetings and broader communications.

“You can tell a lot about an organisation by how people behave in meetings,” she says. “Are people speaking openly? If someone dissents – especially when challenging someone higher in the hierarchy – is that encouraged? Do others stop and listen? Do they follow up on the feedback? Do they give that person some latitude, even delegating authority for them to explore the issue further?

“These are signs of a free flow of information in all directions. In that kind of environment, if you want to make things happen, there’s some receptivity to it.”

Read HRM’s article on addressing authority bias.

When that openness exists, you’ll see people identifying their key stakeholders, building a support base and engaging in productive discussions. After the meeting, conversations continue; people exchange information because it helps move initiatives forward.

On the ‘unhealthy’ end of the spectrum, HR might notice people self-censoring, she adds.

“It’s not just that questions or challenges are met with bad responses, but that people have already learned not to ask them in the first place. So meetings are quiet. Information only flows one way.

“Then, outside the meeting, you see small groups huddling in hushed conversations. When you approach, the conversation pauses – unless they already see you as an ally. Instead of openly working on problems, people manoeuver behind the scenes or vent in private. That’s when influence shifts to backchannels – not just informal ones, but destructive ones.”

Why HR need to become strategic politickers

Idea in short: HR practitioners often avoid organisational politics, but influence is essential for driving results. Power and choice exist on a spectrum – while HR has authority in some areas, true impact comes from strategic influence. Skilled leaders navigate this space by building relationships and securing buy-in, rather than relying solely on compliance.

Overbeck believes some HR practitioners tend to shy away from playing office politics – likely because of its negative connotations.

“HR people tend to have a more humanistic view and they’re also generally pretty rational. I think this can mean they don’t always [see the point] of engaging in political processes within an organisation.”

Political skill is required for those who are interested in gaining power and influence – which may include those working in HR – but it’s also crucial for those who need to drive results, which is everyone working in HR.

“You quickly learn that if you charge ahead with your project without engaging those around you, it’s likely to fall flat. Without support, gaining agreement for your initiative becomes difficult – especially when others have already built strong backing for their own ideas.”

Another reason HR practitioners may not have honed their political influence skills as much is that much of the work they’re doing is backed by regulations and laws, says Overbeck, meaning they can say, ‘This is something you have to do,’ and employees will comply.

In any organisation, influence operates along two key dimensions: power and choice. Some decisions are enforced through authority, while others rely on persuasion and voluntary buy-in. The way leaders navigate this spectrum determines whether they foster collaboration or breed resistance, says Overbeck.

“All the things we do to influence each other sit within this two-dimensional space – they can be high power with little choice or there can be high choice with little power. And then there are all these things in the middle.”

“If HR sends out a compliance email saying, “You are legally required to report X by this date,” that carries authority. If they follow up with, “Failure to comply will result in suspension,” that’s even higher on the power scale.

At the opposite end, persuasion looks more like, “Could you chat with Joe about supporting this initiative?” – a request with no direct consequences.

“Instead of openly working on problems, people manoeuver behind the scenes or vent in private. That’s when influence shifts to backchannels, not just informal ones, but destructive ones.” – Jen Overbeck, Professor of Management at Melbourne Business School

The challenge for HR – and many leaders – is that they often sit somewhere in the middle.

“HR has power, but there is sometimes also choice, which can make it frustrating because they might have to chase people for compliance. People who are very humanistic like to work in the high-influence space rather than the high-power space.

“They make a lot of requests but, without consequences, those requests often go ignored. So what happens when no one takes action? At some point, they have to ask: How do I ensure compliance, especially when there’s a legal requirement? This is where HR and leaders often quickly jump up to high power – using their authority to enforce compliance.

“When you use power to get people to do things, they’ll comply. They’ll do what you say, but it’s public compliance. They’ll do it outwardly, but they don’t necessarily believe in it or internalise it.”

She says skilled organisational politicians learn how to operate in the high-choice space and know how to stay there – even when they face resistance.

“If one person isn’t responding, who else can they engage? Who has influence?

“If Joe refuses to cooperate, forcing him isn’t the only option. Instead, I might turn to Ash, who has a strong relationship with Joe. By getting Ash on board, I create a natural advocate – someone who can have a productive conversation with Joe without coercion. I’m not relying on authority; I’m using strategic influence. Joe still has a choice, but I’ve found a more effective way to move things forward.”

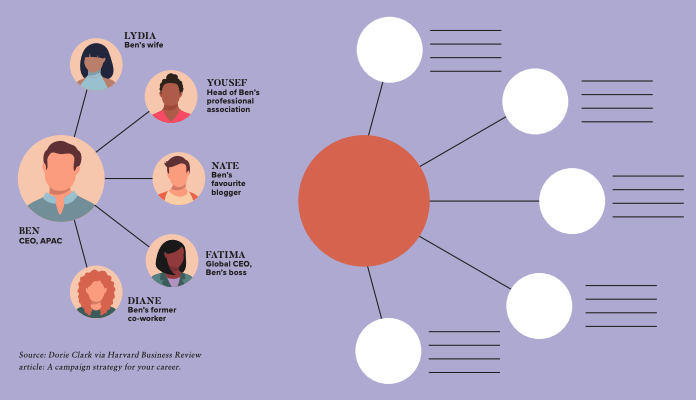

Resource: Read HRM’s article on how to develop a ‘power map’ for strategic influence.

Overbeck says one way to stay in the high-choice space is to “think at least three no’s in advance”.

When we try to get something done, we often picture an easy ‘yes’ – but that’s rarely how it works. People resist change, effort or resource allocation, so their first instinct is often to say no, she says.

“Expect the first no, the second no, and even the third. Then ask yourself: What’s my next move?”

It could mean approaching someone else, adjusting your pitch, offering a new incentive or reframing the request.

“Just that mindset shift is huge – it prevents people from feeling stuck after the first no and jumping straight to using authority. Instead, they stay adaptable and keep the conversation moving.”

Learn how to effectively overcome stakeholder resistance with this short course from AHRI.

Keeping negative office politics at bay

To wrap up, Fidock and Overbeck share practical tips for minimising the negative effects of harmful workplace politics.

Quick tips:

What’s happening between those vying for power? says Overbeck.

Is there clear role separation, or are they competing for a promotion? If their rivalry stems from limited resources, it’s rational but potentially harmful. Can KPIs be adjusted to encourage collaboration, like measuring support for other teams?

Navigate this dynamic carefully but assertively, says Fidock.

“Gather concrete evidence – employee feedback, surveys, exit interviews – to identify patterns and validate concerns.”

If needed, HR can escalate concerns to senior leadership or the board.

“If resistance continues, interventions like executive coaching or formal corrective action may be necessary.”

“In coaching, I’d ask managers what they believe it takes to get things done,” says Overbeck. “Then, I’d explore obstacles to more constructive approaches and listen. If these behaviours exist, it’s likely because they’ve learned them as necessary. That might mean rethinking what we reward or how we respond in meetings.”

“This starts with setting clear expectations for respectful, open communication and holding leaders accountable for an inclusive, transparent culture,” says Fidock. “Confidential reporting channels, anonymous feedback tools and pulse surveys help surface issues without fear of retaliation.”

“Open forums, skip-level meetings and leadership Q&As break down hierarchy barriers, while recognition programs that reward collaboration reinforce positive behaviours,” says Fidock. “By prioritising trust, HR can shift from a fear-driven workplace to one where employees feel empowered and valued.”

Great article, powerful insight. Being influential is more important and skillful than being powerful.

Great article with many valuable points and useful tips for HR professionals. Another consideration that I would like to add is that the trust and influence that HR can get from management and staff also come from being seen as an independent, fair and transparent support function. HR getting involved too much in politics can undermine the level of respect and trust HR can get from senior management and staff.