Employees’ confidence in job opportunities is waning, and discretionary efforts are on the rise. Should employers really want this situation?

A lot can change in a very short amount of time.

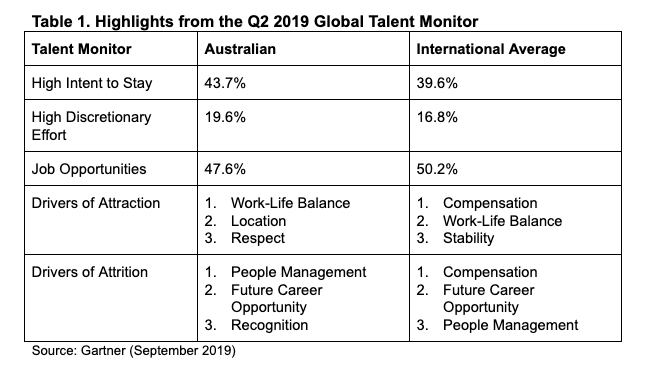

This week research and advisory firm Gartner released its second quarter Global Talent Monitor (GTM) – surveying 1,851 Australian employees – which shows that active job searching in the last three months has decreased by nearly 7 per cent, with 13.4 per cent of respondents signalling their desire to stay put with their current employer.

These results differ greatly from what we saw in the first quarter GTM. Conducted just three months ago, it showed that active job searching had increased by 5.6 per cent.

So what’s changed? It turns out the economy’s unclear future is the prevailing factor for this shift.

Rumblings of an imminent recession have been going on for some time now, but they came into the foreground in early May when Donald Trump escalated the US/China trade war which saw some big companies announce workforce reductions.

Since then, it seems, employees have come to feel they are on unstable ground – the Q2 GTM results show that many have lost faith in the chances of gaining employment outside their current role.

Compare the pair

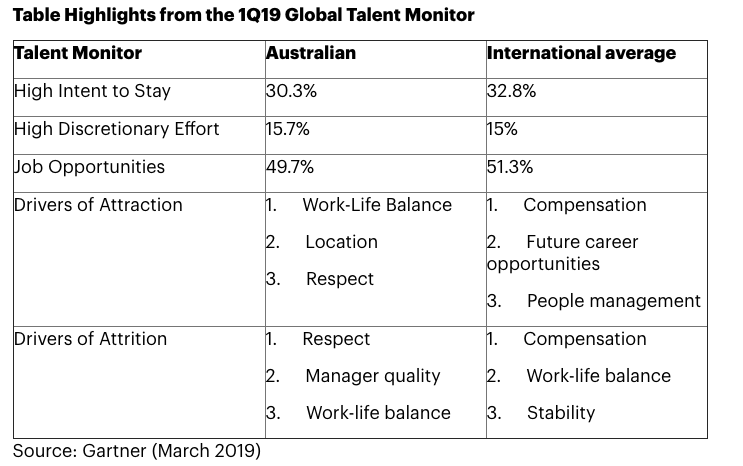

Looking at the highlights (below) from the last two quarters, it’s clear that the biggest changes – other than an increase in employee’s intent to stay – are drivers of attrition. At the start of the year, a lack of respect and the quality of managers were the top two things driving staff out the door.

Now people management, future career opportunities and a lack of recognition are at the top. These three things all fall directly in HR’s bag. While this is worrying, it also represents a good opportunity for HR to step up to the plate.

The bad kind of increased effort?

Even though the outlook of employees is getting gloomier, they are giving a 3.9 per cent increase in discretionary efforts (a willingness to go above and beyond). Compare this to first quarter GTM results which showed that discretionary efforts dropped to its lowest point since the first quarter of 2014.

This might seem like a win for employers, but they should be wary, says Aaron McEwan, vice president in Gartner’s HR practice. “The worst way we could interpret that is that we have an engaged and committed workforce. We’ve got the opposite. It’s not just a burnt out/stressed out workforce, it’s also one that’s highly fearful of the economy. This is not a great combination.

“It’s apparent that in the midst of economic uncertainty, workers are going into self-preservation mode, digging in while they hone their skills and increase their employability.

“Just because you’re working harder or working longer hours – say you don’t want to be seen as the first person to leave the office – that doesn’t mean quality work is getting done. People could be extending their hours without adding more value.”

If fear is the driving force behind increased discretionary efforts, it hurts business in two ways. Firstly, absenteeism rates are likely to increase. That could be because people are taking more sickies because they feel their hard work isn’t being recognised, or because they’re suffering from actual psychological distress from overwork. McEwan says the latter can take four to 10 times longer to return to work.

Secondly, once the fear is gone, so too is the effort.

“We’re coming to the end of the year. People might be working harder to try and secure their bonuses. And if they do, and they feel they have more financial security and stability, we might see them looking for a new job in the new year. They’re no longer scared or motivated to increase their efforts to avoid losing their jobs.”

A recession?

It’s important to note that even though it seems more employees believe a recession is coming, that doesn’t mean one is coming. But, to dwell on the unpleasant for a moment, what should HR do to prepare, and react, to a recession?

In a downturn, HR professionals really have to be strategic and think of new, creative ways to manage the people function.

One way to reassure staff – and avoid cutting too many jobs – is to go around to your workforce and ask who would like to work four days instead of five. This can be a great first step and a win for both employers and employees.

“We saw a handful of very smart companies doing this in the GFC. This is a golden opportunity for organisations to go out to their workforce and ask for volunteers who might already be interested in a reduced amount of hours,” says McEwan.

Traditionally, mass workforce cuts are reactionary and not well planned out.

“If you cut too deeply into your workforce as a short term response to economic uncertainty, when the economy turns positive again, you’ve lost so much institutional knowledge and capability, and you’ve potentially damaged your employment brand. That means it’s harder to attract people to your business and it’s harder to recover when the economy turns again,” says McEwan.

“If you’re a head of HR, the smart thing to do right now is to be making strategic decisions about potential reductions.”

91% of surveyed practitioners say HR certification made them more equipped to think strategically and measure the impact of HR intervention. Find your certification pathway today.

McEwan suggests you do a thorough analysis of your workforce and look at your talent in three steps:

- Firstly, identify critical talent – who are the people you really need to hang on to?

- Next, look for areas that you could source more cheaply (automation, offshore or utilising the contingent economy)

- Finally, find the jobs that aren’t aligning with your future direction. This is where you can apply workforce reduction strategies.

This is a fine balancing act; you can easily go too far in the other direction by overburdening your high performers. These are staff who have the combination of skill, aspiration and engagement with the business’ values.

To put some data behind this, Gartner research shows that high potential employees bring 91 per cent more value to the organisation than non-high performing staff, and they also offer up 21 per cent more effort than their peers.

“One of the big mistakes organisations make in an economic downturn is only letting go of people who aren’t considered ‘high potential employees’. This is assuming that those high potentials want more opportunities,” says McEwan.

“High performers might look like they’re engaged on the surface. They’re doing great work, they’re delivering value, they’re stepping into the vacuum that other team members have left, taking on additional work and working longer hours. An employer could look at them and think, ‘Wow, what an amazing employee. Look how dedicated they are!” But they might not be. When the economy turns, if they haven’t been treated the right way, they will go to a competitor.”

High performing employees are also more likely to be poached. The lesson here is diversify your workforce with people of all levels.

The other mistake employers make is cutting the employees who cost them the most, but aren’t absolutely essential to the bottom line.

“That means you’re losing years of experience. There’s some really interesting data showing that employee productivity doesn’t really kick in until about four or five years of tenure and it tends to go up from there. Cut those people out and you’re left with less experienced people doing really complex work.”

Where to from here?

So how can you ensure your organisation is standing on stable ground as we move into the next quarter? McEwan says the best way to prepare for economic uncertainty is to invest in your talent.

“With bonus and pay freezes on the horizon, organisations should use development opportunities as recognition to encourage good people to stay.”

Now of all times, you should not be cutting into staff development budget, but it’s usually the first thing to go, says McEwan.

“We know that if you make people more employable, they become more loyal. Now is the time to invest in your critical talent portion. Give them opportunities to enhance their capabilities and learn new skills.”

To underline his point, McEwan refers to those businesses who came out on top during the GFC. Success in this time was underpinned by making “intelligent, bold bets” on investments. He uses the example of Telstra investing in the 4G network. The way to stay on top during these uncertain times, he says, is to make those big, bold intelligent investments in your critical talents.