It’s important to understand the various push-pull factors that influence an employee’s decision to switch jobs.

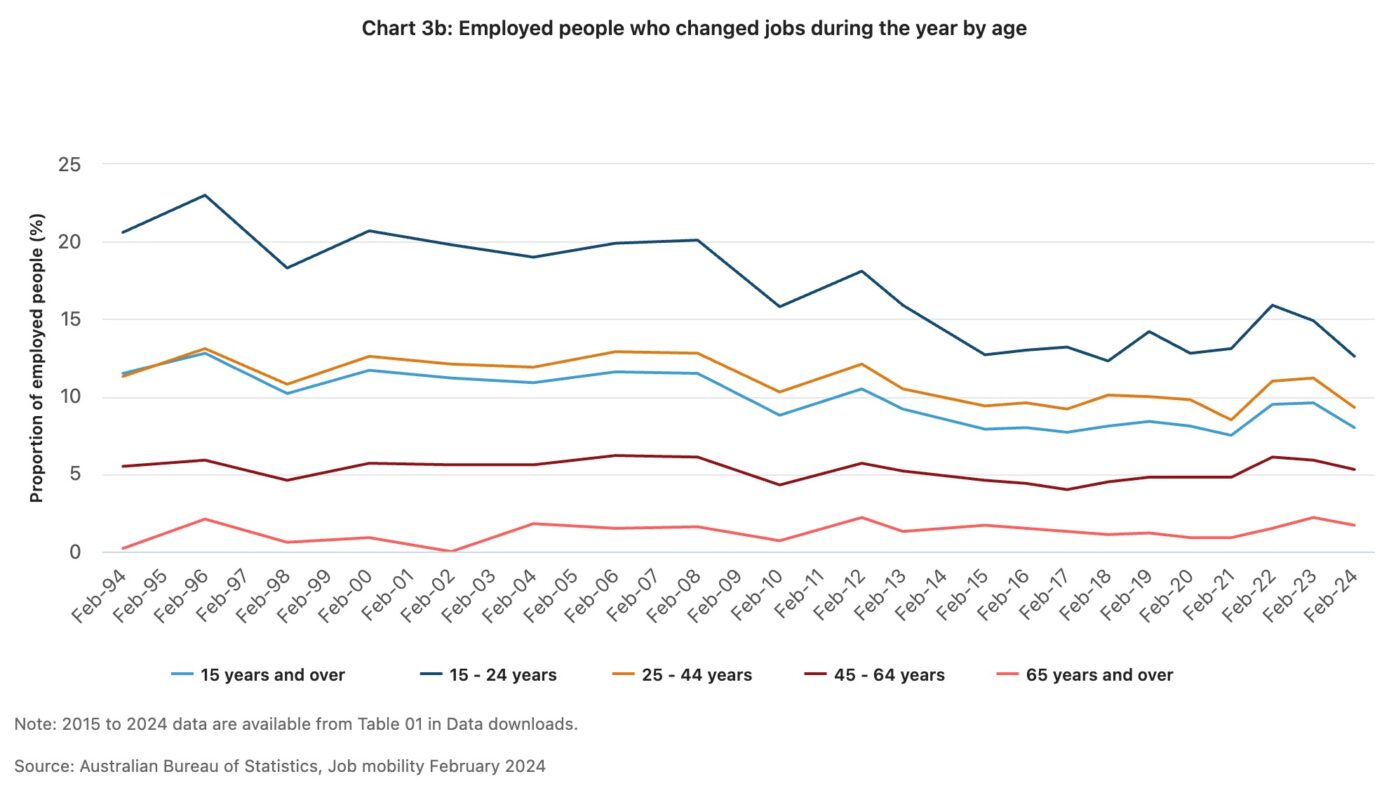

It’s common to make assumptions about why employees quit their jobs. We often think it’s primarily in search of higher salaries or, for younger employees – the most likely cohort to job-hop (see graph below) – we might attribute it to unrealistic expectations or a lack of commitment.

But the reality is more complex. In most instances, employees leave for reasons unrelated to money or entitlement, says Ethan Bernstein, Associate Professor in the Organisational Behaviour unit at Harvard Business School.

“There’s a perception today that to make real progress toward your career goals, you need to switch jobs more often.

“The average job switch happens about once every four years. For certain generations and in certain regions, it’s even more frequent. People are making progress by switching jobs in a way that’s different from previous decades.”

Often, this is driven by a sense of anxiety about job security rather than simply because someone is seeking a fresh opportunity.

“My speculation is that [this is because] the lifespan of a skill is much shorter today than it was 40 years ago. If you’re not constantly upskilling, [it can feel like] you risk becoming irrelevant in just a few years. That creates anxiety, impatience and a strong drive for self-investment and self-reflection. This is what pushes some people to change jobs – they’re building a portfolio of skills to support the career they want.”

Bernstein also highlights a shift in career expectations.

“Traditional career progression pathways didn’t account for how life, circumstances and interests would change. [Employees were previously] more reliant on [their] organisation and its leadership to offer new opportunities.”

But today, career progress is increasingly self-driven. Switching jobs has become a more accepted – if not expected – part of the journey. The challenge for HR practitioners and leaders is to gain a deeper understanding of employees’ internal motivators so they can build more effective retention strategies.

“The fact that we believe the most fungible tools for retention are money and titles – and that’s what’s going to work to keep people – [is concerning]. We tend to fall back on our trusted devices, even though they haven’t worked for decades.”

Why employees quit: the push-pull factors

Another challenge is that businesses aren’t necessarily set up to nurture talent in the ways employees expect to be nurtured, says Michael B. Horn, adjunct lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and co-founder and distinguished fellow at the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation.

“When hiring for new roles, a lot of companies look internally and say, ‘No one’s doing that role today, so let’s look [externally] for someone who’s doing that role elsewhere.’ They’re not good at understanding the skill sets of their current employees. What are they striving to do?”

Over the past 30-40 years, many employers have come to accept high employee turnover as an unavoidable reality, he adds. This mindset can lead to a passive approach to retention, where efforts to engage employees are deprioritised under the assumption that departures are inevitable.

However, what if organisations took a more strategic approach – one that aligned engagement and retention initiatives with employees’ evolving career goals? The first step is to move beyond assumptions and gain a deeper understanding of the real factors driving employee turnover.

Bernstein, Horn, and their co-author Bob Moesta, President & CEO of The ReWired Group, have collated 15 years of studies on the behavioural patterns of over 1000 job switchers across different career stages, roles and industries. Their findings culminated in their book Job Moves: 9 Steps for Making Progress in Your Career.

In conducting this research, they discovered 30 different push or pull factors that drive people to job switch, including:

- Push: I don’t respect or trust the people I work with.

- Push: The way I am managed is wearing me down.

- Push: I feel unchallenged or bored in my current work.

- Pull: My new job will better fit into my personal life.

- Pull: I will have the freedom and flexibility to do my best work.

- Pull: I will be able to join a tight-knit community that I can count on.

They took those 30 push-pull factors, identified overlapping trends, and collated them into four “quests for progress” – in other words, four themes that determine why people choose to jump ship. They were: leaving to get out, to regain control, to realign your work or to take the next step that’s right for you.

While quests don’t necessarily occur at a specific lifestage, there are some broad patterns they have noticed.

“When people reach a certain level of comfort in their life circumstances, they tend to seek purpose. So the ‘regain alignment’ category tends to be something that comes out more frequently in the later stages of one’s career,” says Bernstein.

“Even the best HR professionals and managers have been operating from a playbook that’s missing at least three-quarters of what actually motivates individuals in the job market.” – Michael B. Horn

Importantly, it’s not about someone fitting squarely in the centre of one of the four categories; there are shades of grey in between, which is why it’s so important for managers to deeply understand their team members’ internal motivators, and to track how they might shift over time.

“We’re trying to help HR [practitioners], mentors and managers give better advice to individuals. You can give great advice to somebody who’s a ‘get-outer’, but it’ll be terrible advice for the other three-quarters of the population. That’s why the framework is valuable. It directs how you would advise somebody.”

1. Leaving to get out

This is often the first type of employee that comes to mind when considering those looking to leave an organisation – someone frustrated by their workload or struggling with workplace relationships.

“They might feel micromanaged. They might feel like their colleagues are asking them to do things that are unethical,” says Horn. “There can be this feeling sometimes like the organisation itself is cratering and so it’s a bad environment. It’s a lot of pushes and not a lot of pulls towards something new.”

This group of job switchers is often heavily influenced by their manager. As the saying goes, people leave managers, not jobs, says Horn.

To address this, organisations must invest in manager training that equips leaders to navigate the modern workforce – whether by leading effectively in a hybrid environment or integrating AI into workflows in a way that supports employees rather than overwhelms them.

Explore AHRI’s Leadership and Management Essentials short course to help uplift capabilities in your workforce.

It’s also common for get-outers to leave because they feel there’s nowhere to grow in the organisation, he adds.

“I was coaching someone the other day. She reports directly to the CEO as a Chief of Staff but essentially functions as a COO – except the organisation doesn’t have a formal COO role. She told me, ‘I’m feeling stagnant. I want to learn more in this area and work with someone who’s a great COO.’ My response was, ‘Why not step into that role yourself? Get promoted and bring in an advisor to help coach you.’ But she said, ‘That wouldn’t work with our organisation’s structure and culture.’

“That should raise important questions. Maybe the conclusion is that the structure is right and it’s simply time for her to move on. But perhaps it signals a deeper issue: have we designed the organisation in a way that limits growth for high-potential employees? And if so, is that something we should reconsider?”

2. Leaving to regain control

People who leave their jobs to regain control often do so in response to external factors, such as personal circumstances, workplace dynamics or shifts in company policies.

“Regaining control tends to be about dialing work up or down in response to life events, though not always. It could be a new family, an empty nest or even a difficult boss making work unsustainable,” says Horn.

This motivation is largely about how employees’ time and energy are being used, says Horn.

“If someone is being micromanaged, they might love their work… but if their manager is double-checking everything they do and offering no autonomy, [that person might be seeking to regain control].”

Things like unmanageable workloads or return-to-office mandates might also trigger this response.

“A lot of people are saying, ‘Actually, I really liked the hybrid or remote setup. I knew how to manage my time, and now this isn’t working for me.’”

“Career satisfaction isn’t about what you want to be – it’s about what you want to do.” – Ethan Bernstein

Employees navigating significant life changes may also seek more control over their work-life balance.

Horn offers a personal example. After a decade running the Clayton Christensen Institute, which he co-founded, he decided to step back following the birth of his twin daughters.

“As Bob [Moesta, my co-author] said to me at the time, ‘It’s not that you’re suddenly not a good manager – that’s still a skill set you have – but it’s draining your energy now.’ And he was right. Even today, I think I could be a good manager, but it just takes too much out of me, whereas before, it was something that energised me. I loved working with and managing people.”

Ultimately, whether driven by workplace constraints or personal transitions, the decision to leave in pursuit of greater control underscores a fundamental need for autonomy and balance.

3. Leaving to regain alignment

For many employees, the drive to leave a job stems from a deep-seated need for alignment between their skills, contributions and workplace recognition.

Those seeking this alignment often feel undervalued, with their expertise and potential overlooked or underutilised.

In their article for Harvard Business Review on this topic, Horn, Bernstein and Moesta note that without meaningful validation, frustration can build, leading employees to focus on the disconnect between their capabilities and the opportunities (or lack thereof) in their current role.

If left unchecked, this sense of misalignment can create a negative outlook, where employees fixate on what their job fails to offer rather than what it enables them to achieve. A simple way to avoid this is for HR to coach managers to have regular check-ins with their teammates to better understand where they might feel their skills are being underutilised.

For example, Horn refers to the example of an employee who was feeling down in the dumps about his job.

“After taking our assessment, he discovered he was spending too much time on tasks that didn’t align with his strengths or what he wanted to be doing. So, he picked up the phone and called some of his team members and said: ‘Can you take this meeting? Can you help me with this report?’ He reshuffled his calendar, reallocated responsibilities and within two days everything felt different. He felt so good afterwards. He’d regained alignment without switching jobs.”

4. Leaving to take the next step

Most organisations are structured to support the ‘take-the-next-steppers’, says Bernstein. These employees follow a clear, linear career path: moving from entry-level roles to more senior individual contributor positions, then into management, and eventually to director-level roles.

“For them, it’s the natural next step in a progression they’ve always envisioned for their career,” says Bernstein. “When they leave, it’s typically because they’ve found a role with more responsibility and a bigger title.”

Because their trajectory follows a predictable pattern, organisations find it relatively easy to plan around these employees.

But not everyone fits this mould. Misidentify an employee as a next-stepper, and you risk pushing them toward a promotion they don’t actually want, leaving them disengaged or dissatisfied.

“A lot of organisations assume that everyone wants to take the next step, even though, very often, they don’t,” says Bernstein.

Read about Telstra’s two-stream progression pathway.

Instead of assuming, leaders should focus on understanding what truly motivates their employees.

“Our research shows that for at least three-quarters of people who switch jobs, traditional career progression – bigger titles, more responsibility – isn’t what drives them,” says Horn. “That means even the best HR professionals and managers have been operating from a playbook that’s missing at least three-quarters of what actually motivates individuals in the job market.”

Rather than trying to force-fit employees into a predefined path, Bernstein suggests a different approach.

“How do I help them find the right opportunity, even if it’s outside the organisation, in a way that keeps them loyal to me as a manager, to HR, and to the company? If I do that well, they might boomerang back later in their career, and I’ll still see the value of my investment.”

What can HR do about it?

So what practical steps can HR practitioners and managers take to identify an employee’s career quest and respond effectively?

1. Help employees reflect on their internal motivators

“The most impactful role HR can play is providing ongoing support [for managers] to help individuals understand what progress means for them,” says Horn.

“Self-reflection – assessing where you are, what you need and how your context is evolving – takes time and isn’t always easy to navigate alone. When an organisation actively supports this process, it creates space for employees to reflect, ask the right questions and gain clarity on their next steps.”

Questions that could help an individual uncover their push-pull factors include:

- When was the last time you thought about leaving? What drove this?

- What tasks make you lose track of time?

- When did you last feel completely in control of what you were doing?

- When do you feel you’re at your best?

Read HRM’s article on helping employees to find their ‘red thread’ tasks or the questions to ask in a stay interview.

2. Consistently address energy levels

A key part of helping employees identify which quest they’re on is shifting their mindset from being to doing, says Bernstein.

“You have to move beyond the features and attributes of a job and focus on the experiences it provides,” he says. “If you think about what actually keeps you engaged at work, it’s the experience.”

For example, someone might be drawn to the idea of being a leader because they associate leadership with attributes like confidence, gravitas and respect. But if they were to deeply assess the skills required to be in a leadership position – such as making tough calls, being removed from the detail, networking with external stakeholders, etc. – it might not be all that appealing or energising to them.

With this in mind, help employees reflect on what energises and drains them at work.

“Have them look at the patterns over time. Understanding these trends helps clarify their true priorities.”

Bernstein emphasises that this shift in perspective is crucial in preventing employees from ending up in get-out mode.

“One of the biggest insights we hope [the process of identifying] energy drivers and drains provides is that career satisfaction isn’t about what you want to be. It’s about what you want to do,” he says.

“We’ve seen many people take a job because of a title – [for example], wanting to be a professor only to realise you don’t actually want to publish academic papers.”

That disconnect leads to dissatisfaction and, ultimately, turnover.

3. Create shadow job descriptions

Most organisations assume that job descriptions provide a clear outline of what a role entails, but the reality is far messier.

“What percentage of your work matches your job description?” says Bernstein. “Even in organisations that carefully craft these documents, by the time someone has been in the role for a year or two, the answer is often just 20-40 per cent. The world changes, but job descriptions don’t.”

This disconnect creates a challenge in hiring and retaining employees. Standard job descriptions tend to be bloated lists of skills, qualifications and vague expectations that rarely reflect the day-to-day realities of the role. This is where shadow job descriptions come in. These are informal but more accurate versions of what a job actually entails.

Bernstein compares job descriptions to real estate listings. A house listing might highlight features like granite countertops, north-facing light and in-built storage, but that’s not what buyers truly care about.

People want to imagine themselves entertaining in the kitchen, spending time with loved ones, or having space for their creative ambitions. It’s about the experience, not just the features, he says.

The same applies to jobs. Employees aren’t just looking for a title or a checklist of skills. They want to understand what their daily work will feel like, how their contributions will matter and whether the role aligns with their long-term aspirations.

This is why traditional job descriptions often fail to attract and retain the right people.

To bridge this gap, organisations should focus on:

- Clarifying the real work – Go beyond generic job descriptions by defining what success looks like in the role and what challenges employees will face.

- Go beyond the formal detail – Identify the informal, evolving aspects of a role that aren’t written down but significantly impact an employee’s experience.

- Focusing on experiences, not just qualifications – Instead of a rigid list of skills, help employees envision the actual work they’ll be doing and how it aligns with their career goals. The same goes for when you’re describing promotion opportunities for existing employees.

Ultimately, retaining employees isn’t about clinging to outdated playbooks or assuming that a pay rise or promotion will keep them engaged. It’s about understanding the deeper forces driving their career decisions and creating an environment where they can see a future for themselves.

People don’t just leave jobs – they leave misalignment, stagnation and structures that no longer serve their goals. If organisations want to hold on to their best talent, they need to stop treating retention as a game of incentives and start treating it as an ongoing conversation about progress, purpose and potential.

This article is so enlightening and revealing. It resounds with ebery thing I am facing right now. Thank you so much